A year of change on

Pico Boulevard

A trip fFrom Santa Monica

to Downtown L.A.

A trip fFrom Santa Monica

to Downtown L.A.

Los Angeles imposed coronavirus restrictions on restaurants, bars, gyms and other businesses on March 15, 2020. It was the beginning of a year of loss, upheaval and constant adaptation.

Public health rules kept evolving. Relief programs brought help for some but only red tape for others. Supply chains were a mess. There were shoppers who feared even entering stores and customers who crowded newly built patios.

Some businesses cut hours, services and staff, or closed altogether. Many have survived beyond their expectations.

A trip down Pico Boulevard shows how much has changed one year later.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Ocean-view suites and the breezy patio restaurant at Casa del Mar emptied out when tourism cratered. Its owner fell delinquent on a $357-million loan for the 145-room luxury hotel and another of its high-end Santa Monica properties.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

It was a big fall for a hotel that before the pandemic commanded an average room rate of $698 a night — $281 higher than similar spots nearby, according to industry research. The owner, a hospitality company, missed at least three monthly loan payments between May and September, according to Fitch Ratings.

Then, a reprieve: It secured a deal, resolving the defaults and modifying and reinstating the loan. For now, the owner appears to be staying afloat.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

People are working from home, so they’re all looking at their walls all day and figuring out … ‘I’m tired of looking at this blank wall.’

Reclaimed Frame owner Glenn Friedman, whose Santa Monica framing shop shifted from mostly wholesale business, aimed at gallery shows, to mostly retail, as people redecorated their homes.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Lares Restaurant was caught off guard last March when business restrictions took effect, with workers ushering diners out the door in the middle of service.

But the longtime Mexican restaurant, just past 29th Street, caught a few breaks: It received a federal Paycheck Protection Program loan to help keep workers on the payroll, and it had a parking lot it could use as an outdoor dining area. The Lares family owns the Santa Monica building that houses the restaurant, protecting it from the rent obligations that sunk so many others.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

And then California eased up on alcohol restrictions.

“The fact that we can sell our delicious margaritas to go was huge,” said waitress Martha Lares, 43. “That’s where the money is.”

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Between lessons, performances and people just sampling the wares, it was always loud in McCabe’s Guitar Shop, which faces 31st Street.

Now it’s quiet.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

“Concerts went to zero. Lessons dropped to 5% of what it was,” said Walt McGraw, who has been running the 63-year-old shop with his wife, Nora, since her parents’ retirement in November. “We’re seeing a lot of repair business from people who are stuck at home and want to play. Consignments are up a lot.”

McCabe’s was helped by a $150,000 PPP loan but hurt by a virus-strained supply chain.

Plexiglass and partitions are going up in anticipation of the day when the store can have more than a handful of customers inside at a time. Plans are afoot for an outdoor concert space. “We miss the people,” McGraw said. “We miss the music.”

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

In-person shopping at Erba Markets just off Centinela Avenue dropped by half last March as customers opted to have their cannabis delivered. Dispensary owner Jay Handal saw opportunity.

His delivery business has since more than tripled, even as in-store sales have recovered.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

“People have a lot of anxiety, people are out of work, they’re sitting at home all day,” Handal said. “Our business has just boomed.”

With revenue up, Erba has expanded its staff from 64 to 89. The success makes Handal feel like “the anomaly on the boulevard,” where other shops have struggled and a homeless encampment near his store has grown.

Handal opted against applying for a PPP loan, saying it would have felt immoral competing against struggling bars and restaurants. More than 1,300 businesses with Pico Boulevard addresses have been approved for PPP loans.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

San Francisco Saloon in the Sawtelle neighborhood hasn’t served a drink since March 15, 2020. That was two days before St. Patrick’s Day, among the sports bar’s busiest days, and just as the reality of COVID-19 was gripping the state.

With no patio for outdoor drinks or distancing, the bar didn’t have many options. The first six weeks of closure alone brought $100,000 in losses, owner Bruce Beach said. The business later qualified for a $125,000 PPP loan, but coronavirus restrictions prevented it from reopening in time to spend the money, which Beach now has to return.

Salvation could come with a green light for full-capacity indoor dining. Reopening at 25% capacity, as he’s now allowed, won’t cut it to be profitable, Beach said. Much has already been lost: 29 employees out of work all year, zero annual revenue. “It’s been a nightmare for this type of operation.”

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Billingsley’s Restaurant defined old-school dining in L.A.: prime rib, upholstered booths, dark wood paneling. “Literally you will walk into 1956,” said Brad Pomerance, who hosted trivia contests at the West L.A. restaurant founded by the husband of actress Barbara Billingsley, the mother in “Leave It to Beaver.”

The ambience is what went missing when the restaurant near the 405 Freeway locked its doors, said longtime patron Lilli Lee: “You never really went because you were craving it. You just kind of went there because it was comfortable.”

These days, the kitchen serves as a takeout and delivery outlet of Byte to Bite Industries, an L.A. company that operates restaurants and online-only food brands.

The company is looking to reopen and operate Billingsley’s once rules allow indoor seating at 50% capacity.

Since 1947, Apple Pan had been a cash-only business.

“If you didn’t have cash, they pointed you across the street to the bank,” co-owner Shelli Azoff said.

When Azoff and her husband, Irving, bought the burger joint off Westwood Boulevard two years ago, she promised former owner Sunny Sherman that they would make few changes, except maybe adding a credit card reader beside the vintage cash register.

“She just looked at me and didn’t say a word,” Azoff said.

On March 17, 2020, after COVID-19 temporarily relegated restaurants to takeout-only service, the restaurant began taking credit cards. It also joined delivery app Postmates for a few weeks and built outdoor seating for up to 78 people.

The additional capacity — Apple Pan’s iconic U-shaped counter seats 26 — has helped offset some of the lost dine-in revenue.

“We’re doing OK, you know? We’re making it work,” Azoff said. “We’re still in the black, but the margins are much less.”

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Mika Gonda watched the debut virtual performance at the Pico not from her normal spot in the audience or from the sound booth, but on her cellphone.

A shift in safety restrictions let shows restart at the performing arts space near Rancho Park — with no audience.

“I hop on this YouTube channel and I am looking at the Pico, beautifully lit as if it were a real live show, and I am sitting on my porch with tears streaming down my cheeks,” the venue’s creative director said.

Her in-laws, the locally prominent Gonda family, own the business and are committed to keeping it running. They’ve also lent the eatery next door, John O’Groats, space for outdoor dining, a big help when pandemic restrictions slashed revenue there by half.

“That’s the kind of love we’ve been getting,” John O’Groats President Paul Tyler said.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Demand has never been greater at Temple Isaiah Preschool. Every day, parents call director Tamar Andrews begging for a spot.

“In the state of California, there’s four children for every spot in child care, and that was pre-pandemic,” Andrews said. “I have parents yelling at me on the phone, threatening me, cajoling me, bribing me — anything to get a spot for their child.”

The waiting list has swelled to 200. But the West L.A. preschool is allowed to operate at only half capacity, resulting in layoffs of veteran teachers.

“Our typical enrollment was 348 children a year. And now because of COVID, 174 is the maximum that we’re allowed to have,” Andrews said. “Nobody’s screening how many people walk into a Target or a Home Depot. We are governed so much more strictly.”

As infections rose and anxiety spread, Ralphs and other grocers offered bonuses to front-line workers putting their lives on the line. They called it a “hero bonus,” or “appreciation pay.” But those pay boosts dried up quickly.

This month, Los Angeles began mandating temporary $5-an-hour bonuses for essential workers. The grocery industry has pushed back, saying its margins are too thin to keep wages up.

Grocery giant Kroger, which owns the Ralphs chain, announced March 10 that it would close one of its Pico locations in May, saying the added pay accelerated its decision to shutter an underperforming outlet.

Jessica Lopez, a clerk at the store, didn’t expect a few months of extra pay to be so controversial given the risks of the job: “Anyone who comes in could have COVID. They touch groceries that we touch. I think about it every day.”

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Raquel Lezama used to work as a housekeeper and minibar attendant at Mr. C Beverly Hills, an upscale 137-room hotel just south of its namesake city. She was one of 40 workers laid off last March as travel dropped.

The single mother of three went from earning $17.66 an hour to collecting unemployment benefits and relying on a food pantry. Sometimes it’s not enough. She recalls feeding her family only beans and rice for a month.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

In recent weeks, timesheets provided by the union representing the hotel’s workers show that Mr. C has had as few as four guests booked per day and three or fewer housekeepers.

Mr. C received a $1.5-million PPP loan and is obliged by city regulations to rehire Lezama once demand picks up again.

“I have hope that I will return, but I don’t know when,” she said.

April 2020 was supposed to be the debut month for one of last year’s biggest restaurant openings, from the couple behind the celebrated Republique.

Three months into 2021, Bicyclette in the Pico-Robertson neighborhood sits empty — menu after menu scrapped as the seasons change. Chef and co-owner Walter Manzke said he is ready to “move fast” to open now that limited-capacity indoor dining is allowed again. But it won’t happen overnight after the yearlong holding pattern. “I haven’t even hired the staff for that,” Manzke said.

When it’s ready, Bicyclette will be a casual 70-seat French bistro downstairs and a 60-seat tasting-menu restaurant upstairs. “Hopefully it pays off for all of us that have stuck through this,” he said.

Charles Boateng, manager of the Headmaster Barber Shop in L.A.’s Pico-Fairfax area, counts himself as lucky lately if he does six haircuts in a day.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Before the pandemic he’d sometimes do 10 or 11, surrounded by other barbers and their own clients. Customers waiting their turn would spill out onto the sidewalk.

Now it’s much quieter. The barbers who rent seats at this neighborhood stalwart have also seen business drop by about half since the pandemic hit, and many are collecting unemployment benefits to scrape by, Boateng said. “What can we do?”

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

It’s like with lemons, make lemonade. With catfish, we made tacos. I tried not to be depressed during that time or pissed off at anybody. The restaurant person is always ready for battle.

My 2 Cents chef-owner Alisa Reynolds, who launched a pop-up, Tacos Negros, two blocks from Headmaster Barber Shop during the pandemic to supplement sales at her soul food restaurant.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

I’m not the only pizza guy I know who’s done better through this. I chalk it up mostly to the comfort food thing. There’s never a bad time for pizza.

Bootleg Pizza owner Kyle Lambert, who grew his business from a food truck selling about 30 pies on a typical Friday to a new Mid-City storefront that churns out 180.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

About 100 people gathered for the opening party at Design Hive on March 1, 2020. Two weeks later, Lauren Arshad and Jennifer Cefaly, co-owners of the arts-and-technology studio in Mid-City, found themselves hosting a “make your own hand sanitizer” class. Within a couple of days, they shut their doors.

They hadn’t planned to start a business at the dawn of the pandemic, but they didn’t give up, even when they didn’t qualify for a PPP loan. They sold craft kits online and held Zoom workshops. Arshad put off leaving her job as a schoolteacher to keep the studio open part time.

“We are proud to still be here,” she said.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

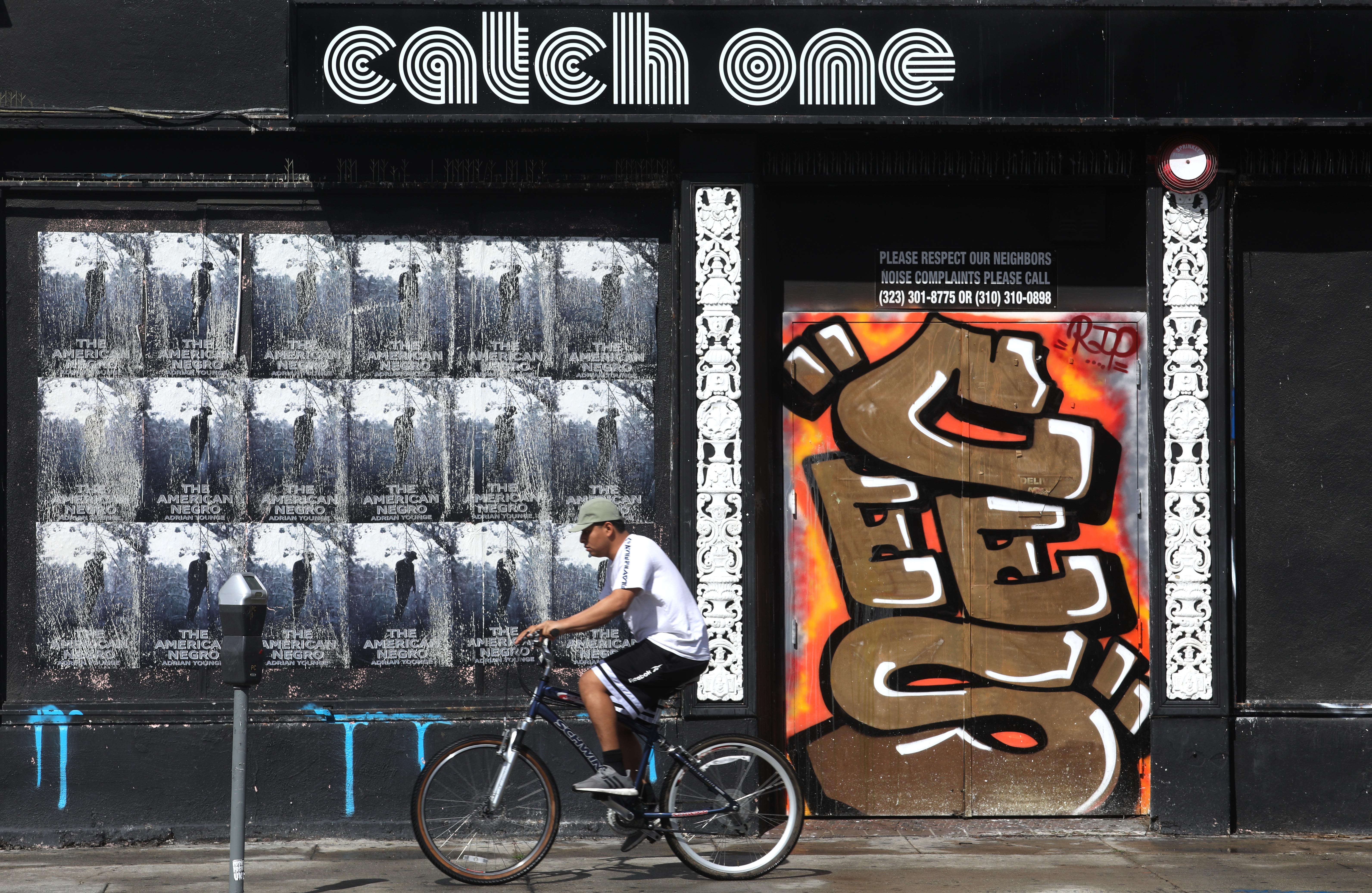

Catch One was L.A.’s first nightclub for Black LGBTQ customers. It’s been a year since the venue near Crenshaw Boulevard has hosted a show — “the worst year of my life,” owner Mitch Edelson said. “I’ve lost millions.”

Edelson, who took over the club from founder Jewel Thais-Williams in 2015, leaned on his event-planning background and a $150,000 PPP loan to keep the business going.

It’s now serving as a ghost kitchen for nine restaurants, with some club employees trained to cook. Catch One leases parking spaces to other businesses for food preparation as well.

“We have small profits some months, small losses on others, but having these revenue options once we reopen is really going to be a game changer for us,” Edelson said.

Extra Space Storage off Normandie Avenue is nearly out of space.

Restaurants hit by indoor-dining bans are stowing tables and chairs. College students moving back in with their parents until in-person classes resume are stashing beds, sofas and lamps. Businesses cutting down on office space have mothballed their furnishings.

Now 96% of the building’s units are rented out, up from about 93% before the pandemic.

The uptick isn’t limited to Los Angeles: Extra Space representative McKall Morris said many of the company’s storage facilities nationwide are at all-time-high occupancy rates. Extra Space hasn’t had to furlough or lay off any employees or cut their pay, she said.

“Life transitions sometimes require additional space, and 2020 put a lot of us in new life situations,” Morris said.

When Maria Elena Cerrón, 89, shut the doors of Botanica Luz del Día, customers couldn’t browse for their preferred veladoras or stop into the Pico-Union store for tarot readings or cleansing services.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Her grandson, Anthony Ponce, and daughter, Dora Cardona, decided to get the shop online. Sales rebounded. “The website is booming right now,” Ponce said.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

In early March, Cerrón went viral on TikTok, bringing in even more customers. A younger generation has embraced the spirituality that the botanica offers, which Cerrón said was considered more outré when she opened in 1984.

She’s gotten vaccinated but is still holding off on performing cleansing rituals. “She internalizes when she does that, taking the bad energy out of people,” Ponce explained, and there are too many bad vibes to go around these days.

With the shutdown of travel and conferences, the Los Angeles Convention Center saw only an eighth of its average yearly visitors in 2020. Annual revenue fell to $13.9 million from $33.8 million. But new uses have sprung up for its big spaces.

Last spring, the 900,000-square-foot downtown facility turned into a surge field hospital for a potential overflow of COVID-19 patients — thankfully, never used. Next, it became a de facto Hollywood studio for TV and film crews whose usual soundstages aren’t big enough to keep crew members distanced, as now required.

The parking garages stored roughly 3,000 vehicles, stowed away for a rental car company while demand was dormant.

We are a walking advertisement right now. Every single person who drives up gets curiosity.

Cecilia Moran, owner of Hardcore Fitness Downtown L.A., who has taken her boot camp classes onto the sidewalk in front of her gym due to COVID-19 health restrictions.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Electronic beats pulse through Rave Wonderland and out the door of the neon-lit downtown shop, a glaring contrast from the boarded-up storefronts down the street. Using Instagram and TikTok, the festival-wear store has managed to draw business from people who want to dress up even if COVID-19 means they can’t go out.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Raves are on hiatus, but the rave crowd is still buying online, said marketing manager Ghazaleh Javidzad. Shoppers remain inspired by the looks of influencers, but that content is now shot in-house, not at festivals.

The top seller in 2020 was a new streetwear line: sheer mesh tops, fishnet skater skirts and faux leather belts.

Workers used to stream through Cafe Esquinita early morning, grabbing coffee and a bite before starting their shifts at factory jobs in the adjoining downtown building. Now they line up for temperature checks at the back, bypassing the café.

Outside, makeshift food sellers advertise $5 lunches out of the trunks of their cars, attracting customers looking for cheaper options. “We can’t compete,” owner Benjamin Chun said.

Business is down more than 50%, and he blames it in part on rules that for several months barred indoor dining: “We are cut off at our knees with all of these restrictions.”

Over the weekend, staff measured space between tables and set up chairs. Regulations have changed so much that Chun almost couldn’t believe he could welcome customers inside the cafe again: “I’ll just wait and see if it happens.”

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times

Quinceañeras. Baptisms. Weddings. First Communions. These milestones of life brought business to Dana Accesorios, a formalwear store run by Laura Manto, 60, and her husband. The shop, in downtown’s fashion district, closed for three months in the pandemic’s earliest, uncertain days. It has since been open but is losing money — depleting the couple’s personal savings and patience.

Their savings, a PPP loan and stimulus checks have all been used up now. “Everything is finished,” Manto said. They are down to one employee, from four.

But this is not the end. Manto expects celebrations and spending to crescendo as schools and church services reopen. “Now me and my husband, we work more. We try to save, save, save. That’s all we can do.”

We're interested in learning how shops, restaurants and other businesses around you have fared over the last year.

If you have a story you'd like to share, please tell us: How has your neighborhood changed during the pandemic?