Column: What a surly California governor’s race can — and can’t — tell us about the Biden-Trump rematch

- Share via

It was a choice few relished, in a dismal election season.

The incumbent was deeply unpopular, spending his entire campaign on the defensive as he struggled to sell voters on his accomplishments.

His opponent, a wealthy businessman, was equally disliked. At one point during the contest he was dragged into court to face fraud charges.

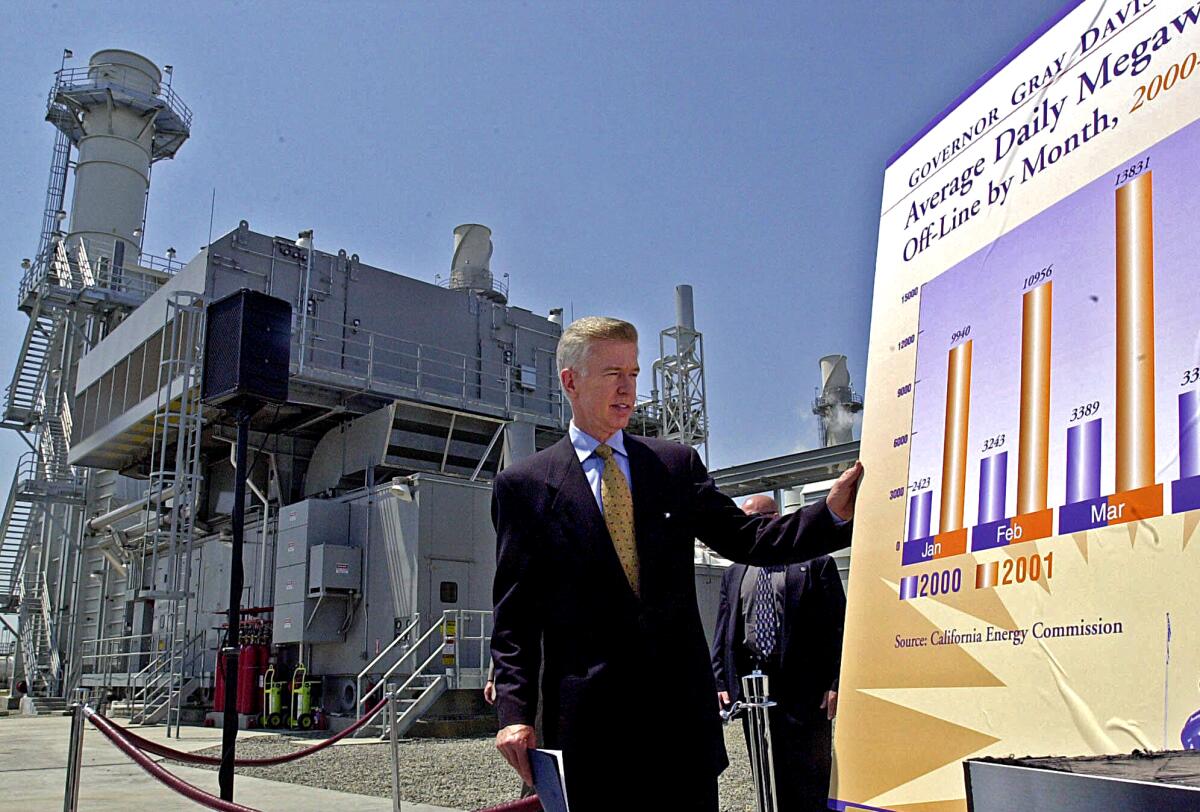

The year was 2002, and Democrat Gray Davis was struggling mightily to win a second term as California governor.

“The night before the election, his favorability was only 39%,” his campaign manager, Garry South, recollected. “That’s something you don’t forget.”

Strategists for Joe Biden can no doubt relate. For the past many months, the president has dwelled in similarly abysmal polling territory. The latest aggregation of nationwide surveys pegs his approval rating at 38%.

No two elections are alike. But there can be striking similarities, like the parallels between that surly California contest 22 years ago and Biden’s tough reelection fight.

Davis clawed his way to a second term despite his wretched approval rating, which is not to say that Biden will win in November. (If he does, he won’t face the risk of being ousted less than a year later, the way Davis was recalled and replaced by Arnold Schwarzenegger.)

Democrat Joe Simitian finished out of the running in a Silicon Valley congressional contest by just five votes. Unlike Trump, he conceded swiftly and with grace.

Even strategists for Davis can’t agree on the lessons gleaned from the Democrats’ uphill reelection effort.

South said that campaign convinced him Biden will ultimately prevail. “I’ve gone through this before,” he said.

Paul Maslin, the pollster for Davis’ 2002 race, is less certain. He makes no predictions beyond his expectation the presidential race will be close. The only similarities Maslin sees between then and now are the candidates’ lousy approval ratings and voters’ sour mood.

But even if past experience is no guarantor of future results, history can inform the way we view existing circumstances — which suggests that, as difficult as things look today for Biden, the president can’t be counted out.

Mainly because of who he’s running against.

“It’s a binary choice,” said South. “Yes, there are other candidates in the race. But in the final analysis, it’s between Biden and Trump.”

David Doak, the chief ad-maker for Davis’ reelection campaign, agreed. He, too, tends towards a glass-half-full assessment of Biden’s chances, suggesting a race between two disliked candidates “is a very different equation than if you’re lined up against someone popular.”

In 2002, Davis faced Republican Bill Simon Jr. The political neophyte was a bumbling candidate who ran a terrible campaign. Compounding his difficulties, Simon was slapped just a few months before election day with a $78-million fraud verdict. (The case involved his investment in a coin-operated telephone company, which, even then — five years before the iPhone was introduced — was a head-scratcher.)

Though the verdict was overturned after just a few weeks, the political damage was done and Davis limped past Simon to a narrow victory.

As it happens, Trump has also been tied up in court. He’s spent the last several weeks gag-ordered and squirming as his salacious behavior is examined in forensic detail at a hush-money, election-fraud trial in New York.

But Maslin, the number-cruncher for Davis’ campaign, warned against getting too carried away with comparisons.

For starters, he pointed out, California was a solidly Democratic state, giving Davis a considerable advantage even as his support flagged amid a recession and rolling blackouts. Biden doesn’t have that partisan edge in the roughly half-dozen toss-up states that will decide the presidential race.

Moreover, Maslin noted, Simon was a little-known commodity, which left the Davis campaign free to define him in harshly negative terms. Trump, by contrast, has been America’s dominant political figure for nearly a decade. His reputation, for good and ill, is firmly fixed; there are plenty of voters who won’t be dissuaded — by rain, sleet, snow, a sexual-assault verdict, multiple criminal indictments — from voting for Trump come November.

Perhaps most significant, Biden is the oldest president in American history and, at 81, very much looks it. Davis’ age — he was 59 when he sought his second term — was never remotely a campaign issue.

“There are many millions of voters who, even if they appreciate Biden’s achievements, still question his ability to serve on the job, much less for four more years,” Maslin said. “I’m not saying that’s accurate, but that’s what they’re thinking.”

In a new district, the fiery Colorado congresswoman enjoys a solid base among the GOP’s MAGA wing. But some are put off by her indiscretions and messy personal life.

Davis, for his part, expects Biden to be reelected, given his record and the contrast he offers to the wayward, unprincipled ex-president. Biden, he noted, has been repeatedly underestimated.

“I experienced that when I ran for governor,” said Davis, who was considered an exceeding long-shot before he romped to victory in the 1998 Democratic primary. “Everyone told me I had no chance to make it, so I know the fire that burns inside you when people say that.”

He’s loath to offer the president advice — “he’s got access to the best minds in the world” — but Davis had this to say to hand-wringing Democrats: “We have a winner. Stick with him. Get excited about him.”

“Because,” the former governor added, “another four years of Trump and you’re not going to recognize this country.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.