- Share via

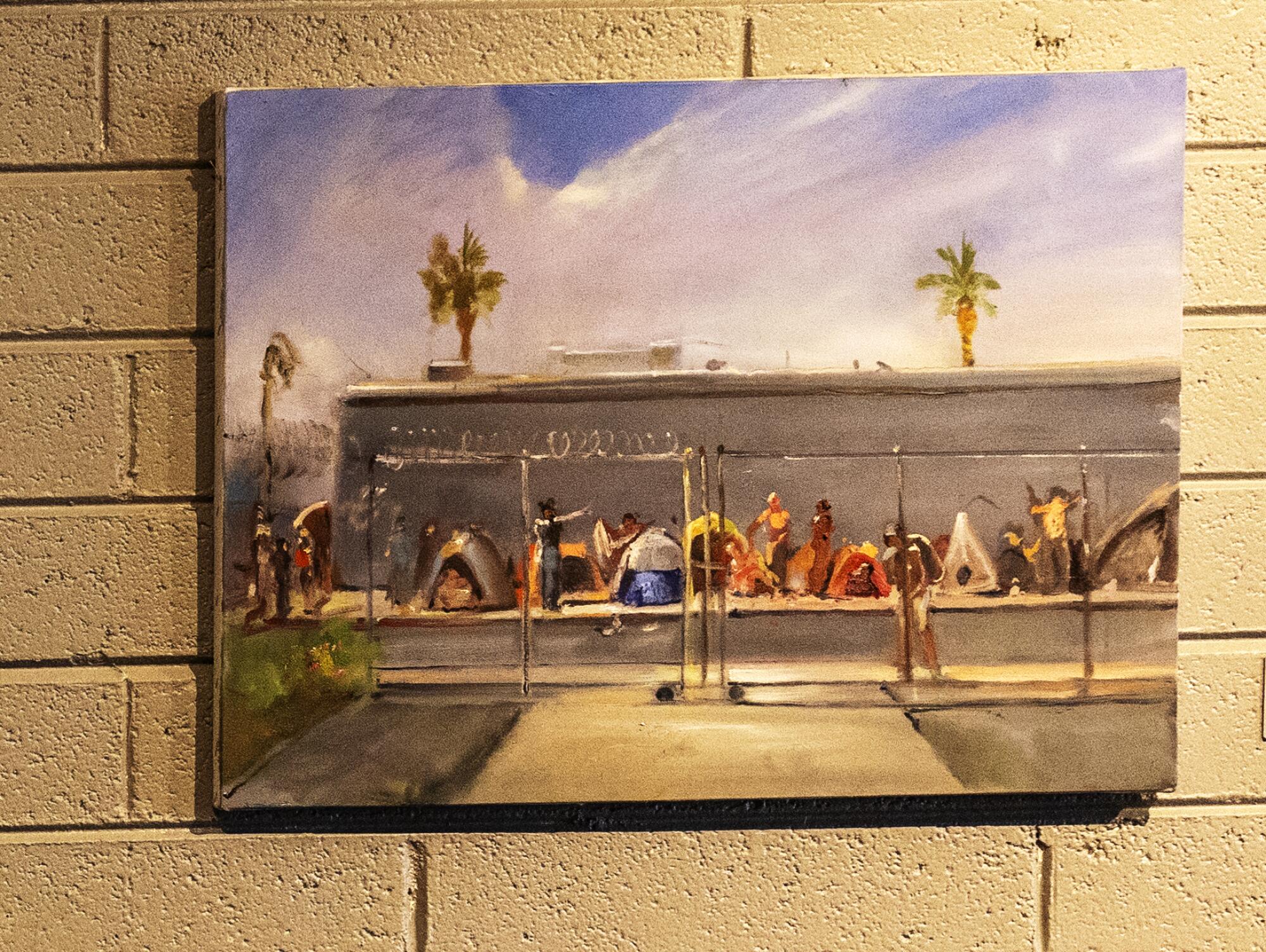

PHOENIX — Artist Joel Coplin has spent the better part of three years painting what he sees through the window of his studio:

A woman showering with a hose beside barbed wire; a body lying still at an intersection under a streetlight.

Then there’s an unfinished piece he calls “The Land of Nod,” an homage to the men and women who seem to defy gravity as they come down from the effects of opioids.

It’s part of a complicated relationship Coplin has with Phoenix’s homeless population, a mix of compassion and frustration.

He and his wife, fellow artist Jo-Ann Lowney, maintain a gallery in an area known as the Zone, about 15 square blocks on the edge of downtown that has been the fulcrum of the city’s clashes over homeless policy. They live above the gallery, making up about half of the housed population in the area.

Coplin, 69, has helped homeless people with food, money and medical bills. He has paid them $20 to sit for portraits, to tell their stories and to listen to his.

Arizona voters will decide on a ballot measure in November that could mean tax refunds for property owners if cities fail to tackle homeless encampments.

But he also has had his face punched and glasses broken when he went to find one of his homeless friends. And he has been a plaintiff in a lawsuit that has forced the city to clear the encampments that were once so prevalent he could not open his downstairs gallery for two years.

“It just ballooned into this incredible, like, barter town,” he said. “They built edifices out of the tents that were like three deep, and 50-gallon drums at night with flames coming out of it — you know, cooking and music and singing and dancing. It was just like an incredible street fair — 24/7.”

Coplin moved to this property six years ago after selling his old art studio, east of the city. It was cheap and he liked the neighborhood’s edginess. He had spent a decade in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen and got used to “stepping over people and junkies and all that.”

People slept on the street beside the gallery when he moved in, but they had no tents and would leave during the day, he said. He helped his neighbors buy things and let them use his bathroom, “sort of like a little community.”

But after the federal appeals court decision restricted the police’s ability to clear encampments, people started handing out tents, he said. During the pandemic, they left again for about a year and then came back.

“So it’s been like coming and going,” he said.

His art studio and gallery, Gallery 119, is down the street from the Key Campus, a 13-acre complex that includes most of the city’s homeless shelters and services. It’s otherwise a relatively barren area, aside from his studio, some warehouses, a few old houses, a sandwich shop, a cemetery and train tracks.

Coplin and other property owners sued the city and won a court order to clear the hundreds of people in the Zone in November. Homeless people still roam the area, but there are no longer clusters of tents.

Conditions are better, but the city still has the wrong solution for homelessness, he said: There should be smaller, more specialized shelters throughout the city, rather than a single super-campus of five blocks.

Rulings by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals have made it harder for officials in California and other Western states to clear encampments. The Supreme Court could take up the issue early next year.

Amy Schwabenlender, the chief executive officer of Keys to Change, the organization overseeing the campus, said clearing the area has brought more people inside the campus, especially during the day. At night is another story.

“But we still can’t shelter everyone so we know X number of people leave every night and they’re sleeping somewhere,” Schwabenlender said. “Not necessarily safe, not meant for human habitation.”

As a Beethoven symphony played in the background in Coplin’s studio, it’s hard to imagine the devastation outside that inspires his paintings. He recalls the night he looked out his window to see what he thought was an object “right in the middle of 11th Avenue and Madison.”

Then he saw movement — “a person!” Cars weaved around but did not stop. He ran down to help. But before he got there, someone else came, and a mere touch startled the person.

“Up she jumped and started running,” he said. “I said, ‘Oh, my God, that’s Elizabeth.’ I knew her.”

Coplin’s portraits have a quiet dignity — a man in a three-piece suit; a woman looking up while she holds her dog, a blanket their only protection from the rain.

He also looks to the past for inspiration. In one group scene, eight people are bent to resemble characters in Diego Velazquez’s 17th century work known as “Los Borrachos,” or “The Drunks.”

He pointed to a historic library down the street that now sits vacant. He is campaigning to make it a museum for the state’s artists. He retains hope that the area can become a place where people will come to buy his art and appreciate the potential he sees.

“This is the final frontier,” he said. “All other aspects of the downtown have been taken up.”

He has always rejected the idea of gentrification, “but now I’m on the other end, and I want the gentrification. And I want condos.”

Recently, someone called to offer him $940,000 for his property, he said. He told them no.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.