- Share via

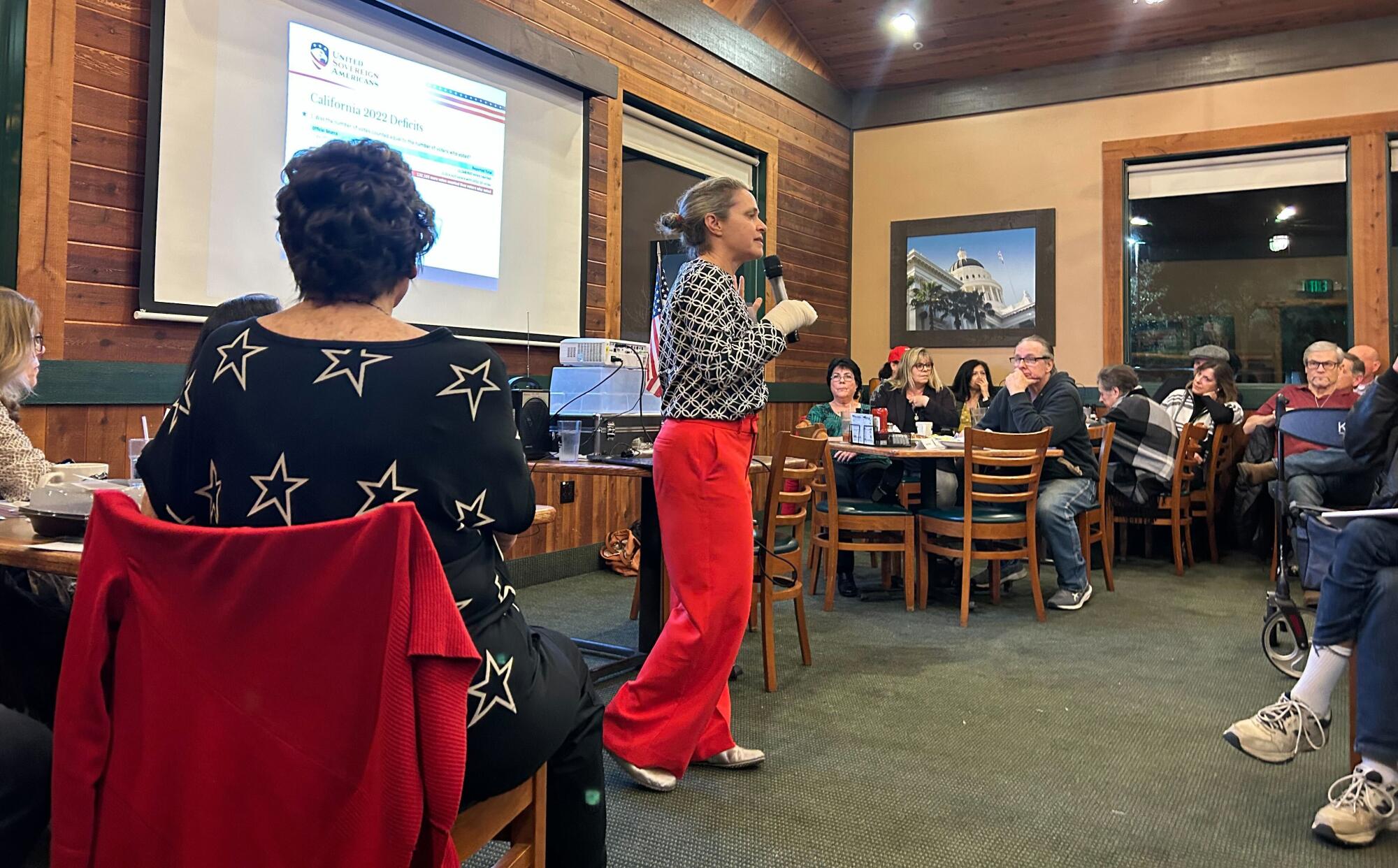

SACRAMENTO — At a diner just off the freeway north of Sacramento, a mostly white crowd listened intently as it learned how to “save America” by leaning on the same laws that enshrined the rights of Black voters 60 years ago.

Over mugs of coffee and plates of pot roast smothered in gravy, attendees in MAGA and tea party gear took notes about the landmark Voting Rights Act and studied the U.S. Constitution. They peppered self-proclaimed “election integrity” activist Marly Hornik with questions about how to become skilled citizen observers monitoring California poll workers.

The nearly 90 people gathered in the diner in February were there to understand how they can do their part in a plan to sue California to block certification of the 2024 election results unless the state can prove that ballots were cast only by people eligible to vote.

A Times series on how election misinformation spreads in America

If any votes are found to be ineligible, Hornik explained, then all voters are being disenfranchised — just like those decades ago who couldn’t vote because of their race.

“If we think our right of suffrage ... has been denied or diluted, we have to stop that immediately. We have to stop it right in its tracks,” said Hornik, co-founder of a group called United Sovereign Americans, which is led by a man who helped push former President Trump’s baseless challenges to Joe Biden’s election in 2020.

The two-hour meeting at the Northern California diner — one of several similar presentations that have taken place across the country in recent months — is part of the group’s plan to file lawsuits in multiple states alleging voters’ civil rights are violated by errors on the voter rolls. The goal is to prevent states from certifying federal elections in 2024 until substantial changes are made to election processes.

What United Sovereign Americans has planned is a legal long shot. But election experts worry that if even one sympathetic judge rules in their favor, it could sow doubts about the integrity of a presidential rematch between President Biden and Donald Trump.

“Sometimes the whole point is to whip up enough smoke that it seems like a fire,” said Justin Levitt, a former deputy assistant attorney general who specializes in voting rights.

The group’s legal arguments rely on faulty interpretations of federal election law and are likely to fail in court, according to Levitt and other experts who believe the group’s evidence of voter registration fraud is overstated and inaccurate.

United Sovereign Americans is part of a cottage industry of far-right election deniers that has sown disinformation since Trump lost his reelection bid. The group aims to scrutinize elections with a legal strategy that can “throw massive amounts of sand in their gears,” Hornik said during a February presentation in Orange County.

Its first lawsuit in the multi-state plan was filed against Maryland election officials on March 6, alleging that the state’s voting policies don’t comply with federal laws requiring accurate voter rolls and thus violate the plaintiffs’ civil rights. The suit asks the court to keep the State Board of Elections from certifying any election until their claims of voter roll irregularities and other election law violations have been resolved, an action that could potentially derail Maryland’s May 14 primary. On April 22, Maryland asked the judge hearing the case to dismiss the lawsuit or, at a minimum, deny the request for the restraining order.

Similar lawsuits are expected in coming weeks in California, Ohio, Illinois, Texas and several other states, Hornik said in an interview. Once they have built a legal fund for the suits, her group plans to file in multiple federal jurisdictions in hopes that judges will rule differently in different areas of the country, causing the Supreme Court to step in and settle the issue ahead of election day, she said.

An ‘ecosystem of grift’

Hornik said she lives in rural upstate New York with her “three home-birthed children” and a small herd of dairy goats. The self-described “home school mom” has long gray hair and the air of a patient teacher as she fields questions and flips through PowerPoint slides explaining her plan to disrupt America’s elections.

She drew laughs from the crowd in Sacramento as she cracked jokes about COVID protocols drawing people into “a medical experiment.”

Hornik became involved in an online community questioning election results while stuck at home during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, then went on to create a group called New York Citizens Audit in 2021. Its members spread conspiracy theories about the results of the 2020 and 2022 elections at events across the state.

In September, the New York attorney general issued a cease-and-desist letter ordering Hornik to stop “voter deception and intimidation efforts,” describing complaints that volunteers with her group had “confronted voters across the state at their homes, falsely claimed to be Board of Elections officials and falsely accused voters of committing felony voter fraud.”

Hornik said at the time that the group was not knocking on doors.

She expanded her efforts after teaming up with Harry Haury, whom she met at a 2022 conference hosted by the group that funded the debunked pro-Trump propaganda film “2000 Mules,” which is based on lies about the 2020 election.

Haury, a St. Louis native with deep ties to the “Stop the Steal” movement, approached Hornik about nationalizing the work of New York Citizens Audit. Haury had been part of a little-known team of self-proclaimed cybersecurity experts who helped search for evidence of fraud in the 2020 election for some of Trump’s closest allies in the weeks after Trump lost. Haury’s background as a software engineer has largely been focused on energy technology.

Together, they created United Sovereign Americans and began recruiting activists in at least 20 states to obtain voter registration rolls and analyze the data for potential errors — such as a person registered at multiple addresses or dead people with active registrations.

Hornik said they have completed examinations of voter rolls in Ohio, Illinois, New York and Texas, and they are finishing that work in California. Florida, Missouri and North Carolina are close behind.

In California, they are working with Election Integrity Project California, a nearly 15-year-old group that has been sending election observers to the polls since 2012. Linda Paine, a former Santa Clarita tea party activist now living in Arizona who leads the group, hosted Hornik for a three-day speaking tour in February with stops in Fresno, Shasta and Ventura counties.

A federal lawsuit that Election Integrity Project California filed to challenge the state’s election laws and procedures was dismissed, but the group has appealed.

The group has trained hundreds of poll watchers to observe whether local officials are following proper election procedures, including during the attempted recall of Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2021.

Paine did not respond to requests for an interview.

David Becker, who leads the Center for Election Innovation & Research, a group focused on restoring trust in the nation’s election system, described the work of Paine and Hornik as “an effort to dismantle election integrity under the auspices of election integrity” amid an “ecosystem of grift.”

“The grifters have evolved,” Becker said. “They used to just say, ‘There’s so many dead and illegal voters on the list.’ And then they started coming up with a really specific number ... as if there was some analysis that went into that.”

The problem, he said, is that voter registration rolls obtained by these groups are a snapshot of a system that constantly changes as people move or die. It can’t be compared to a static event like an election result: “It is not possible to maintain a voter list that is accurate at every single second of every single day.”

As they’ve crisscrossed the country spreading misinformation about election procedures, Hornik and Haury have asked for donations at public events and on far-right media, saying they need millions of dollars for their lawsuits. Their website allows donors to pick which state effort receives funds, with up to half going to the national group. In Shasta County in February, Hornik urged attendees to think about what they can do to help save America in 2024.

The ReAwaken America Tour, a pro-Trump religious roadshow, has become known for promoting Christian nationalism and right-wing conspiracy theories.

“I want to ask you to really look inside yourself and ask yourself what are you called to do to help this mission?” she said, according to a recording of the event posted online.

“Are you called to participate? Are you called to come and work on the resolutions? Are you called to work on the legal briefings? Are you called to write me a $10,000 check today? Because we need money to get this done.”

The civil rights claim

At the diner in Sacramento, Hornik told the crowd that her plan to sue states for alleged civil rights violations should be easier than challenging results based on election laws.

“We believe that this very simple approach can advance rapidly,” she said. “It doesn’t matter if you weren’t allowed to vote or if your vote was drowned and suffocated by invalid ballots, either way, you didn’t really get to vote.”

Hornik argues that people’s constitutional right to choose their elected representatives is violated when the power of lawful votes is diminished by votes cast illegally.

But the entire plan is based on a count of alleged errors in the voter rolls conducted by volunteers who lack expertise in the election system and election law. Hornik’s allies at Election Integrity Project California claim to have counted 257,894 people who voted in the state’s 2022 election despite potentially being ineligible to cast ballots. But they did not explain their criteria for identifying alleged discrepancies in the voter rolls, raising serious questions about their count.

The volunteer analysts’ work is reminiscent of past efforts by “armchair detectives” to examine voter rolls, said Levitt, the former deputy assistant attorney general. Their arguments claiming fraud are also based on fundamental misunderstandings of what is allowed under federal voting laws, he said.

“These are people sitting at home who don’t actually understand all that much about how the election structure works who are trying to impose their will on how the process is supposed to work on the government,” he said.

Douglas Frank has given dozens of speeches alleging voter fraud in California and across the country, and has helped create teams aimed at disrupting state election systems.

And their legal argument is based on a “really troubling” interpretation of civil rights law, said Sean Morales-Doyle, director of voting rights for the Brennan Center for Justice.

“The idea that somehow the votes of ineligible voters is drowning out the votes of eligible voters is not at all based on reality,” he said.

The concept of “vote dilution” stems from a provision of the Voting Rights Act that is meant to give people of color equal rights to elect the candidates of their choice. It typically comes up in disputes over drawing political boundaries where the preferences of a minority group could be diluted by a white majority that votes as a bloc.

“The notion that this puts them in a similar situation to people who are actually being disenfranchised is just not a fair or reasonable analogy,” Morales-Doyle said.

Hornik admits that her group does not expect to win a lawsuit against California. She said United Sovereign Americans intends to file lawsuits in least 11 states across nine federal court circuits. Failing in some and winning in others is part of the strategy to get to the Supreme Court, Hornik said.

“It doesn’t matter that we are going to get turned down in New York. It doesn’t matter that we get turned down potentially in California,” Hornik said. “It matters that we get a favorable ruling in Tennessee and Missouri. It matters that we get a favorable ruling in Texas so that there is a diversity of opinion and ultimately that also means that there is a possibility that the matter is settled for the entire country.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.