Much-needed nurses are flocking to California — for some of the same reasons others are fleeing

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Nurses — those indispensable healthcare workers in desperately short supply nationwide — are streaming into California, a striking contrast to the recent flight of thousands of frustrated residents to other parts of the country.

And in many ways, what’s drawing them to the state is not so different from why others are leaving, namely, the high cost of living and progressive policies.

California’s famously expensive lifestyle has driven away many residents in search of cheaper housing and lower taxes. But for highly sought nurses, that’s translated into the biggest salaries in the nation.

Registered nurses in California on average make more than $133,000 a year, 50% more than nationwide, according to federal labor data.

The top 10 U.S. metro areas for nurse pay are all in California, with the Bay Area leading the way with an average annual salary of almost $165,000 and nearby areas not far behind.

The state’s liberal policies, regulations, strong unions and generous healthcare systems — all frequent targets of conservatives at the national level — have also played a role in helping California combat a nursing shortage that plagues most of the nation, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Californians moving to Nevada hope to re-create a California lifestyle — a tech hub with mountain views — without the Golden State’s problems. It’s not working exactly as planned.

California is the only state to mandate minimum nurse staffing levels at hospitals. Experts say those nurse-to-patient ratios, for every hospital department, have helped reduce the increasingly heavy workloads that are driving many to quit or retire early.

In critical care units and labor and delivery, state law requires at least one nurse for every two patients. It’s one nurse per four patients in pediatrics, and one to five for the general medical surgical floor.

“What a difference the mandate makes,” said Lynsey Kwon, a registered nurse who recently moved to California.

After graduating from a Virginia nursing school in 2019, she went to work at a public hospital in Lynchburg, Va. While the hospital’s internal policy was to have one nurse for every three stroke patients, the reality more often than not was that she cared for four patients and sometimes five at the same time, she said. COVID-19 made things worse.

Two years ago, Kwon, 27, moved back to her native California and took a job at Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center.

Work at the 412-bed hospital, a trauma center serving parts of three counties, is often hectic. Yet Kwon says that in her two years there, she’s never taken on more patients than the state-mandated ratio.

She earned $25 an hour when she left Virginia in 2021. Today she makes almost twice that.

“I don’t know if I could work anywhere else,” said Kwon, who got into nursing because she was in and out of the hospital as a sick child and saw the difference a nurse could make.

Between 2020 and 2022, about 30,000 more registered nurses moved into California than out to other states, according to estimates by Joanne Spetz, director of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at UC San Francisco, which surveys the state’s nursing workforce and tracks licensing data.

Spetz said the nurses coming into the state tend to be younger and less experienced than those leaving. And by most accounts, California still has a shortage of registered nurses.

But the overwhelmingly positive inflow helped expand California’s registered nurse population to 388,463 last year, up 8.3% from 2019, according to a UC San Francisco research report. It probably would have been greater if California were part of a 41-state compact that makes license transferring easier.

The influx of nurses stands in sharp contrast to what has been an accelerated flight of Californians overall since the pandemic. Increased remote-work opportunities have fueled more moves to Nevada, Texas and other states where the cost of living is cheaper and the politics more conservative.

A return to in-person work might seem like a good thing. But some red-state leaders worry the return-to-work economy will limit their talent pool.

When it comes to nursing, however, other states are beginning to copy California, which began to implement the staffing policy nearly 20 years ago.

Oregon’s Legislature recently passed broad minimum nurse-patient ratios for hospitals, which will take effect in June. Massachusetts and New York approved similar requirements but limited them to critical units. Legislators in more than a dozen other states have introduced various nurse staffing requirements, despite often heavy lobbying against such laws by hospitals.

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, a nursing professor in Eugene, Ore., and president of the American Nurses Assn., expects the Oregon staffing law to “absolutely help hospitals recruit nurses.”

Yet in light of the nationwide shortage, she noted that gains in one state might only exacerbate needs in others.

Nationwide there are some 5 million people with active registered nurse licenses; only about 70% are employed in nursing full time, Kennedy said.

With the pandemic, many more left the increasingly taxing work of bedside nursing, taking jobs at doctors’ offices or clinics or as case managers.

Older nurses in droves opted for early retirement. Nationally, the median age of nurses is now 46, a full six years lower than in 2020, said Maryann Alexander, head of nursing regulation at the National Council of State Boards of Nursing.

Nurse turnover nationally, although easing a bit since last year, remains rampant, at 22.5%, the American Nurses Assn says. It’s been especially high at nursing homes and acute-care hospitals.

Moreover, nurses — hailed as heroes early in the pandemic — now complain they often feel unappreciated, by patients and hospital administrators alike. Nurse walkouts are more common today, as Garfield Medical Center in Monterey Park saw last month over staffing, workplace conditions and pay.

SEIU United Healthcare Workers West said nearly 60,000 workers in California had approved a possible strike, teeing up what could be the biggest strike by healthcare workers in U.S. history.

“I was told you were easily replaceable,” said Jessica Sites, 46, who worked for more than 20 years as a labor and delivery nurse at a hospital in east-central Florida but quit last year. Sites said she was so overloaded that she usually went without lunch breaks. And the problem wasn’t just about clinical care.

“Majority of my day I felt my back was turned from patients because I had so many boxes I had to check,” Sites said, referring to administrative duties and paperwork.

Hospital groups argue that government nurse-staffing regulations aren’t necessary, saying many medical centers use a team-based approach that allows for greater nurse independence and flexibility to meet the ebbs and flows of patient cases. Mandated ratios, they say, would backfire and worsen the nursing shortage.

But Linda Aiken, director of the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research at the University of Pennsylvania, says the opposite happened in California.

When the state’s minimum nursing ratios took effect in January 2004, California had a dearth of nurses. In two years, she said, the shortage was over.

Aiken said studies suggest that California’s nurse-patients ratios also have helped improve health outcomes. Patients in California receive three hours more care per day than those in other states, she said.

But there have been some negative effects and problems as well.

As California hospitals hired more registered nurses, some offset the increased costs by cutting the number of nursing assistants who carry out tasks such as changing bedsheets and bathing patients, UCSF’s Spetz said. Hospital charity care also slowed.

Union leaders say stronger enforcement of the ratios is needed. And many California hospitals still struggle with being short-staffed, especially those in rural areas.

Kaweah Health Medical Center in Visalia, about 40 miles south of Fresno, has a nurse vacancy rate in double digits. Kaweah’s chief executive, Gary Herbst, says he’s tried to help boost the state’s nursing profession through partnerships with local colleges, resident programs and scholarships. “We really want to grow our own,” Herbst said.

He also sends his staff to the Midwest to recruit in the dead of winter. Even then, he noted, it’s hard to attract nurses to move to the more remote region in the Central Valley.

Still, on the whole California has an edge in recruiting nurses.

No other state comes close in pay, a reflection of the strong unionization of nurses, competition from Kaiser Permanente, as well as California’s high living costs. Nurses in New York make on average 30% less than their counterparts in California, and in Texas it’s almost 60% less, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data for May 2022.

And the state’s better working conditions are not only attracting new nurses to the state, but they are also helping to keep some from leaving.

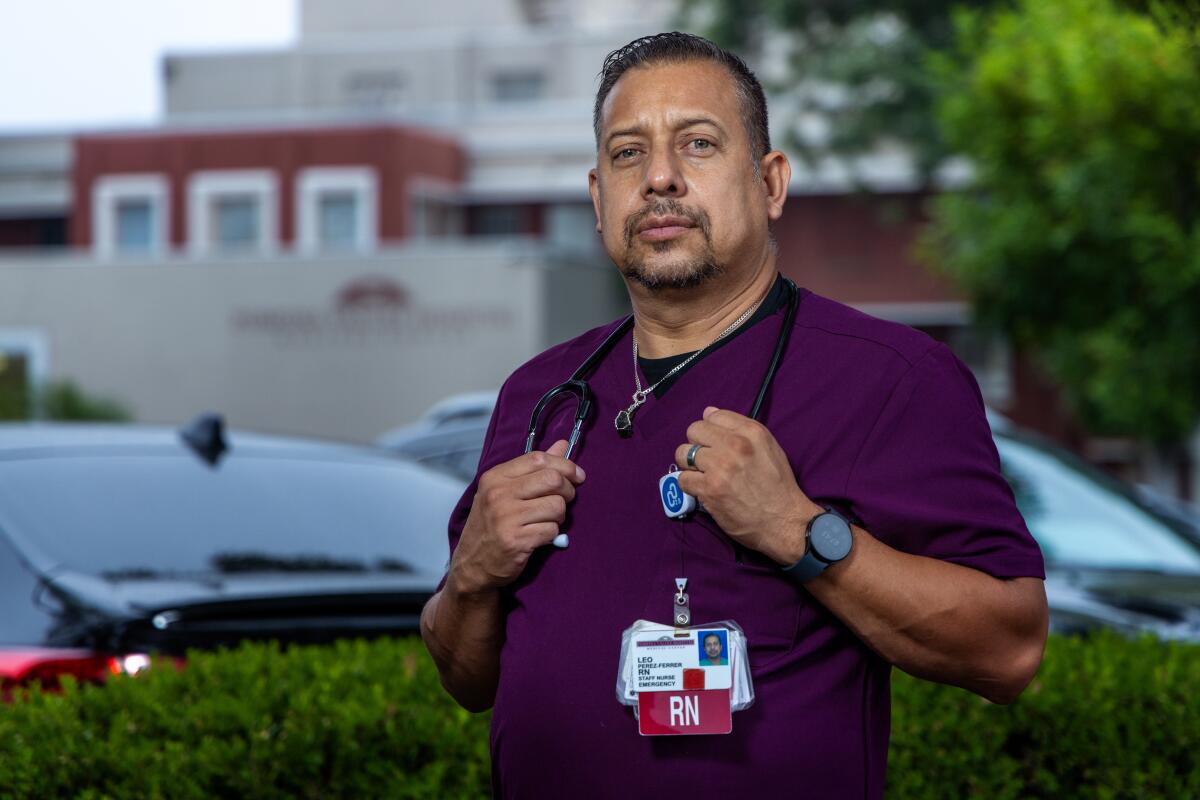

Married nurses Leo and Marlene Perez, who worked side by side for five years at Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center‘s ER unit, have been mulling over a move to Arizona, where they’d like to eventually retire.

Their daughter, also a nurse, already works in Tucson. But they’ve been reluctant to make the move.

Leo Perez, who is 49 and president of SEIU Local 121RN, said he’d be looking at a pay cut of about $33 an hour. Moreover, he doesn’t want to give up the benefits of California’s more favorable workplace climate for nurses.

“I don’t know if I could work in an acute-care setting without nursing ratios,” Perez said, noting that nurses at his daughter’s hospital in Arizona sometimes care for seven patients at a time. “She has horror stories.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.