T-Street Beach in San Clemente is part of the 49th Congressional District, where voters worry about high gas prices as well as energy policy and the environment. (Albert Brave Tiger Lee / Los Angeles Times)

- Share via

SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO — When Amy Sibley heads to the Costco here from her home in nearby San Clemente, her best friend, Lisa Miller, tags along — to save gas money.

“I hitch a ride with her,” said Miller, 58, an unemployed business consultant, as the temperature in the black-tar parking lot topped 100 degrees. “If I put gas in my car, I can only put in five or six gallons at a time. It hurts when you have the minimum coming in and a lot of obligations. There’s only so much you can do — pay the bills or get in the car and drive around.”

Miller is a Republican who voted for Donald Trump in the last presidential election; Sibley is a Democrat who voted for Joe Biden. Both say the cost of gas — and groceries and other goods — is top of mind as they decide how to vote in the November midterm election that will determine control of Congress.

“It’s not about one side or the other,” said Sibley, 54. “It’s about what’s best for the people here. People need to survive. A lot of people are barely making it.”

In this coastal congressional district — which could help determine which party controls the House — gas prices are a key consideration in the run-up to the election, according to interviews with voters and candidates.

The 49th Congressional District straddles Orange and San Diego counties, stretching from Laguna Beach to Del Mar and is home to Camp Pendleton, which has trained generations of Marines who have battled in the oil-rich Middle East. Here, filling up a tank on the way to work is part of the daily routine.

“Clearly gas prices have been the most visible sign of inflation, and that’s particularly true in this district, where people commute up to Orange County or down to San Diego,” said Thad Kousser, a political science professor at UC San Diego who lives in Solana Beach and surfs in Del Mar on his way into the office. “We’re essentially a Marine base and a set of bedroom communities with a lot of people driving SUVs.”

In a deeply divided nation, the one thing unifying Americans is a shared sense of unease. A vast majority believe the country is heading in the wrong direction, but fewer agree on why that is — and which political party is to blame.

This occasional series, America Unsettled, examines the complicated reasons behind voters’ decisions in this momentous and unpredictable midterm election.

Though the district’s affluence cushioned some residents from high prices, the issue is part of a broader debate about the nation’s energy policy — the response to climate change, the stability of the power grid, imported energy, the role of renewables, nuclear, fracking and drilling.

Such issues have dominated recent headlines — fears of blackouts during blistering heat waves, California’s ban on sales of new gas-powered cars starting in 2035, and fines over a 2021 oil spill that closed beaches on the northern tip of the district. The coastal midpoint of the district is studded by the decommissioned domes of the San Onofre nuclear power plant, where radioactive spent fuel rods are buried indefinitely because there is no federal repository for such waste.

Gas prices have shaken Americans this year; 55% said the spike prompted them to upend summer vacation plans, according to a Gallup poll.

Nationally, prices have declined since. But not in California. After dipping for several weeks, the average cost of a gallon of regular gasoline in California was up to $6.38 on Monday, according to the American Automobile Assn. The national average was $3.80.

Statewide offices, congressional seats, L.A. mayor, propositions — including on abortion, sports betting and taxes — are up in the November election.

California’s gas prices have long been higher than the rest of the nation because of state taxes and fees. UC Berkeley economist Severin Borenstein partially attributes the recent price increases to some refineries that make the special blend of fuel that meets the state’s environmental standards being taken offline for maintenance, as well as one having an unplanned outage.

“California uses about 40 million gallons of gasoline a day — about a gallon per person per day,” Borenstein said. “So adding an extra $2 per gallon means that’s an extra $2 per person per day for cost of living. For relatively affluent people, that’s half a trip to Starbucks. For less affluent people, and people who have to drive a lot, which tend to be more working-class people, that can be a significant burden.”

Borenstein noted that voters tend to blame those in power for such pocketbook issues, which have the potential to tilt congressional races.

“Obviously, whenever the price of gas goes up, any politician in power takes some blame for it, no matter how little power they have over it,” he said.

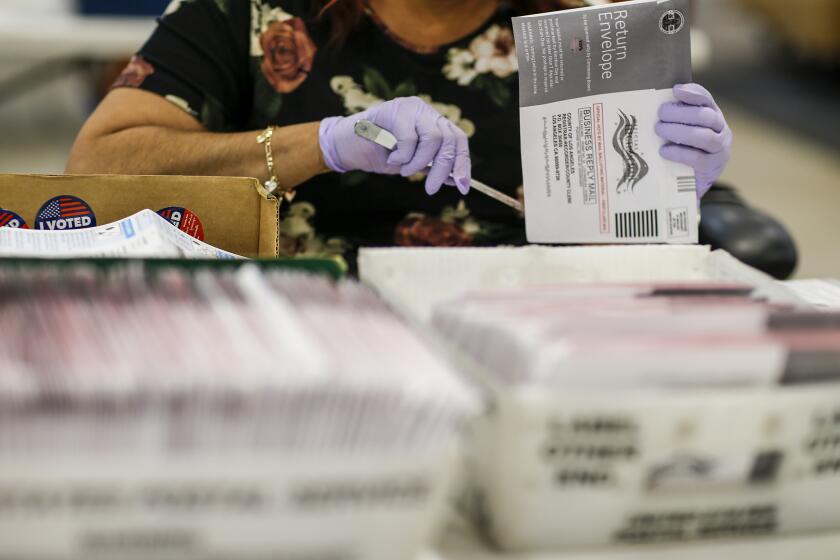

In the 49th District, where Democrats have a scant 2.9% voter registration edge and more than $6.5 million in television advertising has been reserved between now and election day, incumbent Democratic Rep. Mike Levin recognizes this dynamic.

“We are all feeling the pain of inflation. The difference is the other side doesn’t have any concrete solutions,” the environmental attorney told more than 60 seniors at a recent meet-and-greet in a gated Oceanside community.

“I encourage any of you to really try to talk to your Republican friends and neighbors about this issue here at Ocean Hills and say, ‘Well, OK, we can agree that this is a real problem,’” said Levin, who was first elected in 2018. “‘The cost of gas ... the cost of groceries: too expensive. The cost of housing is still too high. But what are your concrete solutions?’”

Levin blamed high gas prices on “the three P’s”: the pandemic, Putin and price gouging. COVID-19 has caused supply chain problems, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted the global fuel market, and opportunistic oil companies inflated rates, he said in an interview after the reception.

“How we wean ourselves off of that is not to double down on the dirty-energy policies of the past. It’s not to spread misinformation or disinformation about the transition to cleaner energy, but it’s to actually embrace a more sustainable future,” said Levin, who voted for the Consumer Fuel Price Gouging Prevention Act and successfully fought for the inclusion of climate change investments in the infrastructure bill.

The first general-election ad aired by Levin highlighted his work to clean up radioactive waste at San Onofre. Levin, who started the bipartisan Spent Nuclear Fuel Solutions Caucus, introduced legislation to prioritize the removal of such waste in areas with large populations and seismic risks; it was co-sponsored by a number of GOP members of Congress.

Levin supporters agree that energy policy is “a very complex global situation.”

“It’s not just an American problem. We’re responding to what’s happening in the world, with energy and with Russia in particular,” said Betsy Quinn, 71, a retired school principal who recently moved to the Oceanside senior community.

Her husband, Christopher Quinn, 70, a fellow former principal who now works as a minister, recently changed his registration to no party preference after a lifetime in the Republican Party because of his frustration with what he describes as its leaders’ intransigence. And he just replaced his car with a hybrid. “I’m stepping one small, expensive step to make it a little bit more responsible,” he said.

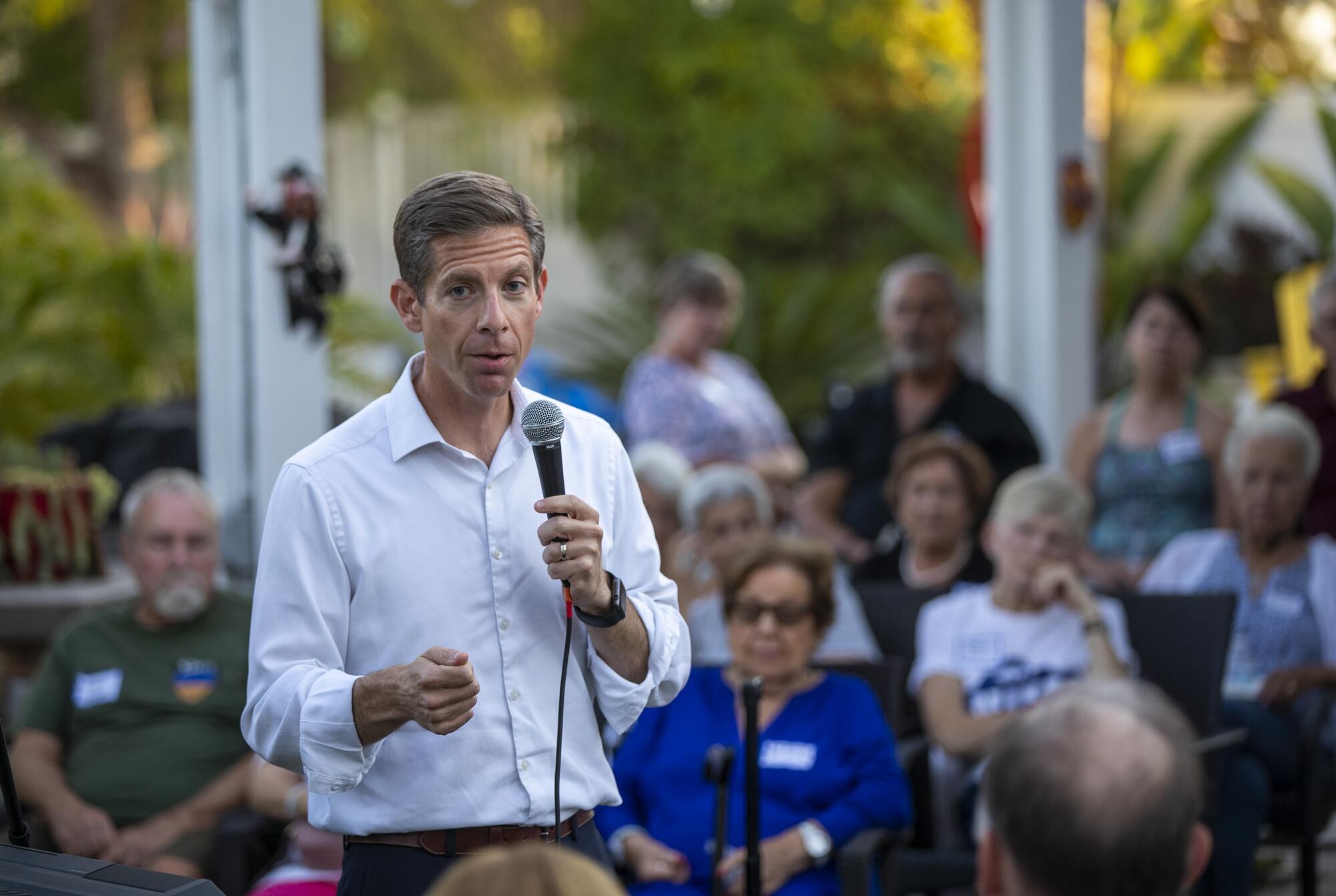

Hours earlier, Republican candidate Brian Maryott and about a dozen supporters gathered at an intersection in Oceanside, holding signs that read “Honk for lower gas prices” and “People before politics.”

Teri Elmore, 63, was among those waving at passing commuters. The recently retired event planner said the nation’s economic woes had upended her post-work plans with her husband.

“We saved our money our whole working lives, living below our means, to retire and travel,” said Elmore, a former Democrat who switched to the GOP in the 1990s. “And now everything is so expensive, right? Our investments have tanked and gas prices just make it harder to go see people. You really think two or three times before you make any kind of trip.”

Elmore said she hoped Maryott, a former Wells Fargo executive, would help Congress reduce spending. And she was confident the nation’s environmental standards would keep the coast safe. “We are the United States. We work cleaner than most countries across the world,” Elmore said.

Historically, Republicans in the area tend to take more moderate positions on environmental policy than in other parts of the country — this isn’t the “Drill, baby, drill” crowd.

Scientists warn that if the emissions created by those fuels aren’t quickly and drastically reduced, the Earth will see catastrophic temperature fluctuations, with far more devastating storms, fires and droughts.

Maryott — a former councilman and mayor of San Juan Capistrano, where Levin also lives — opposes new drilling off the California coast and acknowledges climate change. (In his campaign logo, the “O” includes the outline of a whale’s tail.) But he’s against punitive regulations on businesses. His website places in bold the words “No penalties! No impractical deadlines! No financial punishment!”

California’s 2022 election ballot includes races for governor, attorney general, Legislature and Congress, local contests and statewide propositions.

In an interview in an Oceanside park, Maryott said he believes the nation needs to increase its domestic energy productions through the fracking of shale oil and the creation of liquified natural gas, while also supporting renewables and subsidizing electric vehicle purchases.

“We all care about the generations to come ahead of us, and we know that we’re just passing through. So we’re all very mindful of our responsibility to that,” he said. “But we have to be willing to have a discussion about climate economics alongside of it. We have to be pragmatic.”

Maryott, who unsuccessfully ran in the 2018 district primary and challenged Levin in 2020, said liberal politicians are moving too fast in trying to reduce the nation’s dependence on fossil fuels. He pointed to the state urging electric car owners not to charge vehicles in peak usage hours during the recent heat wave, a week after announcing the 2035 ban on new gasoline-powered cars.

“They can’t shove these things down the nation’s throat without ramification, and those ramifications are coming in November when a good number of them are going to be voted out.”

Some undecided voters, like actor Fahim Fazli, say they want policy proposals, not political broadsides. And the independent voter from Dana Point is looking for some relief from gas prices.

The retired Marine — who served as an interpreter in Afghanistan more than two decades after he fled the country and has appeared in films such as “Iron Man” and “American Sniper” — said the only reason gas prices haven’t gutted him is because so much of his work, particularly auditions, is now conducted virtually.

“As an actor, I used to drive to Los Angeles, drive two hours, come back with traffic, four hours. And I wasn’t worried about the gas. Now, thank God, everything is online. Everything is on FaceTime. Everything is on Zoom,” said the 56-year-old. “I used to fill up my car for $50 bucks; now I fill up for $120.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.