India has become a U.S. partner in countering China — a limited partner, that is

- Share via

WASHINGTON — For more than two decades, American presidents have invested high hopes in a deepening U.S. relationship with India, the world’s largest democracy — as they almost invariably mention.

And at first glance, India looks like a natural U.S. ally, not only an electoral democracy but a rapidly growing economy that fears the expanding power of China.

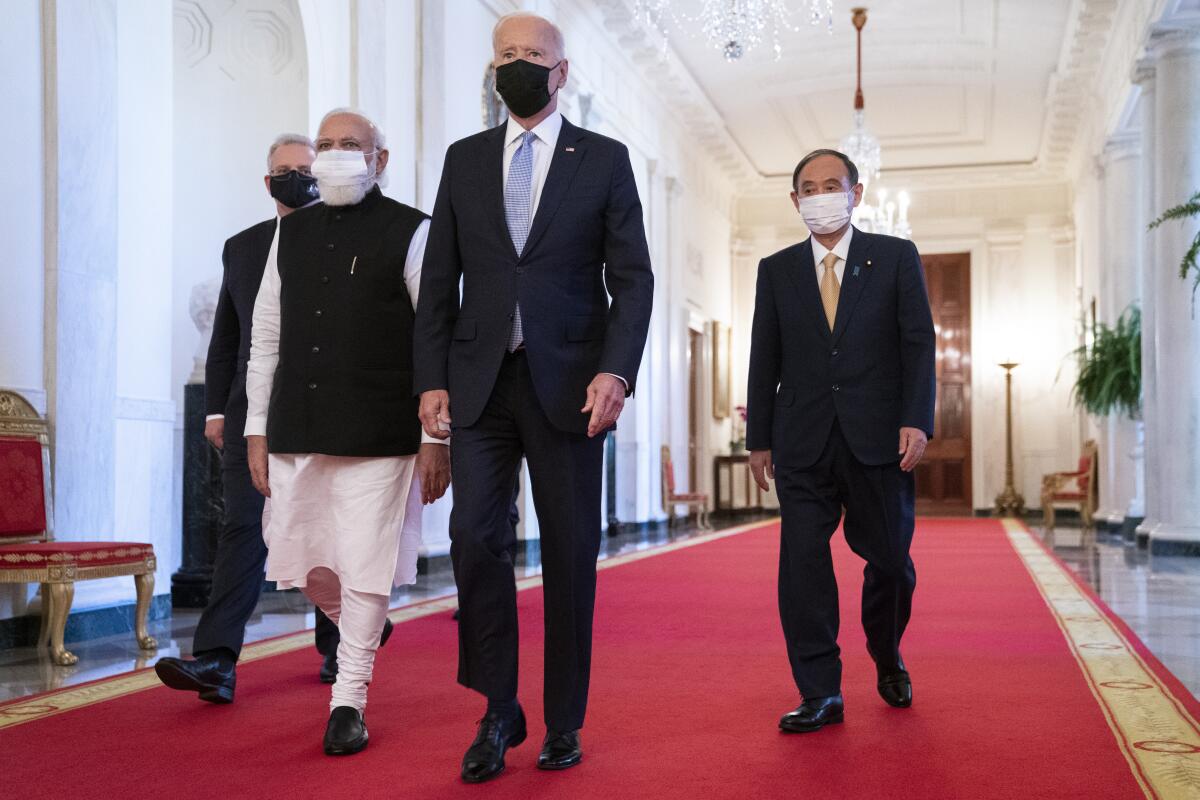

Last year, President Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met in Washington and declared a “global strategic partnership” — not quite a formal alliance, but the next best thing.

How did California become the most populous, diverse, economically dynamic and confounding state in the union? A new book takes a stab at examining that question.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine, and suddenly all those promises of partnership began to appear shaky.

Biden helped organize an international coalition to back Ukraine, including not only European allies but Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea. He waged “a pitched battle,” one U.S. official said, to persuade India to join.

Modi refused. At the United Nations, 140 countries voted to condemn the Russian invasion; India abstained not once but a dozen times. The Indian leader said blandly that he regretted the war, but never mentioned who started it.

India values its relationship with the United States, Modi aides explained, but it wants to keep its ties to Russia too. In the ensuing three months, India has not only continued buying oil from Moscow but increased its purchases, partly because Moscow offered wartime discounts.

This week, Biden will join Modi in Tokyo at a meeting of the Quad, the U.S.-backed coalition of “Indo-Pacific democracies”: India, Japan, Australia and the United States.

The four Quad countries agree on one major goal: They want to counter China’s rise as the dominant power in Asia.

But when it comes to the world’s most pressing crisis, the war in Ukraine, the Quad won’t have much to say because India, the odd country out, is still sitting on the fence.

One reason for India’s refusal to join the global condemnation of Russia is practical: Moscow is its No. 1 military supplier. According to one study, as much as 85% of India’s major weapons are Russian-made. If Russian President Vladimir Putin cut off those supplies, India would soon run out of spare parts for aircraft and missile systems.

This summer, India is expected to deploy its newest weapons system, the Russian-made S-400 anti-aircraft missile.

Another rationale is geopolitics: India sees China, with which it shares a 2,100-mile disputed border, as its biggest threat. The two armies fought a major war along the “line of control” in 1962, and skirmished as recently as last year.

“India is worried that if it condemns Russia, it’s going to be pushing Russia into the arms of China,” said Manjari Chatterjee Miller, an India expert at the Council on Foreign Relations. “That’s India’s biggest nightmare: Russia and China aligned together.”

But there’s also a deeper historical reason for Modi’s caginess: Ever since the Cold War, when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru helped found the Non-Aligned Movement, India has made independence from both the United States and Russia a centerpiece of its foreign policy.

“India has always had an aversion to alliance-like relationships,” noted Ashley Tellis of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The desire not to be part of any camp is deeply rooted in India’s view of itself.”

India isn’t the only country that has resisted the U.S. lead on Ukraine. Leaving aside Russian allies like North Korea and Syria, 35 countries abstained on those U.N. votes, including U.S. aid recipients such as Vietnam, South Africa and Iraq.

Vietnam, like India, depends on Russia for military supplies. Others may have shared India’s aversion to Cold War-style confrontation or merely sought to play both sides.

But India is the most important holdout by far, the most powerful country in South Asia and a key player in the coalition to counter China. And that competition with China, not the war in Ukraine, is still Biden’s top foreign policy priority.

So after an initial flash of irritation — the president griped publicly that India’s position was “somewhat shaky” — Biden has been markedly gentle toward his wayward partner. On India’s purchases of Russian oil, for example, the administration has merely asked that they not grow.

India’s membership in the Quad, including its navy’s participation in joint exercises, is the factor that has allowed Biden to proclaim his Asia policy an “Indo-Pacific Strategy.” The last thing he wants to do is to weaken the four-way coalition by accentuating differences.

India has signed up to be a U.S. partner in Asia — but only a limited partner, and a prickly one at that. That’s a balance that American political leaders often have had trouble accepting.

“Part of the problem here is us, not them,” Tellis argued. “We sometimes get carried away with our own rhetoric. We expect our partners to join us in every cause. In the case of India, that’s a fatal misunderstanding. Can our vision of partnership accommodate India’s perpetual desire for independence?”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.