- Share via

BAKERSFIELD — As dawn breaks over 40,000 cows housed in a miles-long cluster of dairy farms near Bakersfield, rivers of their manure rush toward football-field-sized lagoons that are a hotbed of greenhouse gas, bubbling with the methane created by all those cattle droppings.

To the state of California, this collection of animal excrement is a climate success.

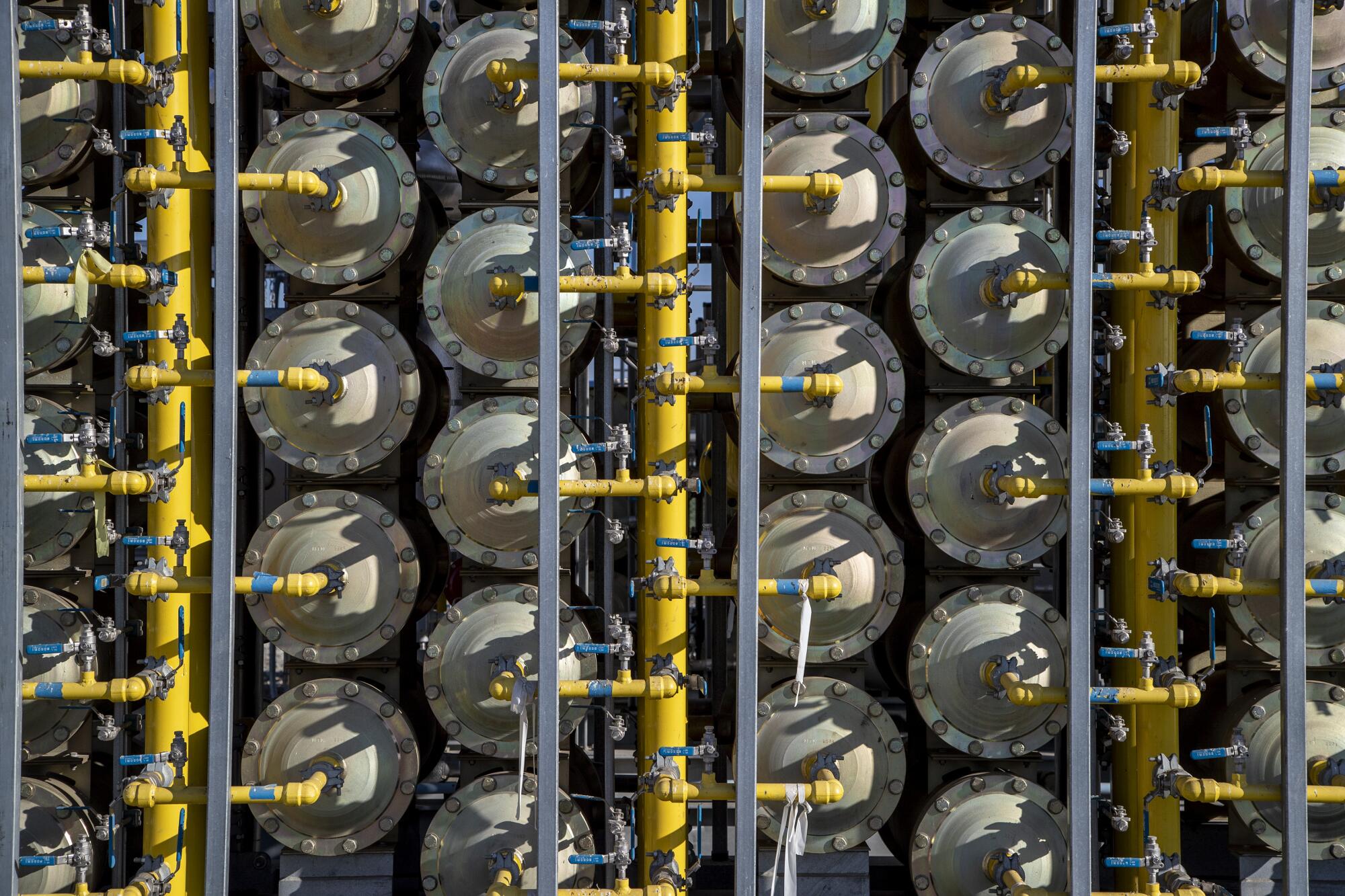

The state has enabled farmers and their business partners in California and far beyond to make millions diverting such methane into a web of futuristic machinery that processes and pumps it into natural gas pipelines.

“With a good natural gas car, one cow could get you across the country,” said Neil Black, president of California Bioenergy, which installs the digesters that trap and repurpose the gas. “In addition to producing milk and cheese and yogurt and ice cream … each cow produces about 125 diesel gallon equivalents of methane a year.”

Yet California’s aggressive promotion of trapped methane and other forms of biofuel has touched off a high-stakes drama. It is drawing cries of protest from some of the most vocal climate activists and words of caution from sober analysts, who warn it threatens to set off an unwelcome chain reaction around the state and across the country.

California is leading the nation into a new era of climate-friendly fuel, or “biofuel,” made out of animal fat, cooking oil and methane from cow manure. These biofuels burn cleaner in engines, but California’s aggressive push for them might fall short as a solution and could be setting off an unwelcome chain reaction around the state and across the country.

As the state tries to lead the nation into a new era of climate-friendly car, truck and jet fuels, it is hitting turbulence. California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard is meant to be an exemplar of the energy transition — a model for marrying the interests of big agriculture and the state’s climate goals that carefully sidesteps the collateral environmental fallout caused by earlier experiments with biofuels.

The effort is leading to fuels that burn cleaner in engines. But California’s climate policies are pushing demand for these biofuels to a place that is sending tremors through the nation’s agriculture economy. The state is trying to strike a balance between hitting its own climate targets while avoiding actions that propel global warming elsewhere. Whether it is succeeding is hotly debated.

Electric cars, climate credit schemes, diverse boardrooms and legal weed: How California exports its ideas and policies across the U.S.

“We are raising an alarm,” said Jeremy Martin, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “We need to clarify how much of this stuff is reasonable to use.... We want to clean up transportation. But we need to be careful not to create a problem in the agriculture sector along the way.”

The methane incentives are so generous that one UC Davis professor warns that the state is nearing a point where it is rewarding production of manure, pushing livestock industries to crowd more of their animals into confinement, and potentially creating more manure — and thus, methane — than otherwise necessary.

Separate from the methane push, California’s bullishness on biofuels is also moving some of the country’s large refineries to retrofit their operations to no longer process crude oil. They are shifting to the business of making “renewable” diesel and jet fuel from plants and animal fats. The projected demand California is driving for these ingredients could outpace the supply, which threatens to touch off a range of consequences from increased food costs to a sharp uptick in palm oil production from plantations that are one of the world’s most potent accelerators of global warming.

“We don’t have all the right solutions yet,” said Gene Gebolys, chief executive of World Energy, which has converted a refinery in Paramount into one of the world’s first operations that makes jet fuel without using a drop of crude oil. “But the stuff we are working on right now will lead to the right solutions, because it has to. We have no choice but to figure this out. The status quo is not going to work.

“To say we need to slow things down is absolute insanity,” Gebolys said. “People lose sight that the alternative is suicide. You’ve got to keep moving to keep improving, and sometimes the moving won’t be perfect.”

Getting low-income communities to transition to electric cars is a key climate challenge for California and the nation. A rural city is paving the way.

California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard is a product of the state’s landmark 2006 climate law. Its goal is to reduce the climate impact of transportation fuels 20% by the year 2030. Unlike other biofuel mandates, California’s requires what is meant to be a meticulous “life cycle” assessment of fuels used in the state. That means fuels are judged not just by how clean they burn, but also by the greenhouse gases created over the course of their production.

So fuels made from waste products that might otherwise make their way into the trash — such as corn husks or used fryer grease — generate the highest incentives in the program. Fresh soybean oil scores lower, as the formula factors in all the resources used to grow and transport the ingredient.

The concept is wildly popular among climate regulators. California’s program is being copied across the nation, with Oregon and Washington already creating replicas. Colorado, New Mexico, New York and Utah are looking into doing the same.

The enthusiasm is driven by a need to create more climate-friendly bridge fuels as the state and nation gradually electrify vehicle fleets. The fuels tend to be targeted at the biggest fuel guzzlers, such as jet planes and long-haul trucks, for which widespread electrification may not be feasible anytime soon.

Even without other states launching their own programs, California’s outsize economy has compelled fuel producers — and farmers — across the country to change the way they do business, as they rush to take advantage of the state’s incentives. Midwest refineries are seeing big opportunity in the California market. Giant hog operations in the heartland owned by conglomerates like Smithfield Foods are converting pig manure into a cash cow.

But this new frontier of transportation fuels is filled with risk. Regulators are trying to limit ancillary damage to food companies unnerved by its potential to boost the price of cooking oils, fence-line communities warning it creates new pollution threats, and small ag businesses accusing the state of helping factory farms squeeze them out.

“This isn’t going to solve our climate problem,” said Tim Gibbons, who leads the Missouri Rural Crisis Center, a group that argued to the California Air Resources Board that it is hurting family farms in the Midwest by rewarding industrial hog operations there that generate colossal amounts of methane. “This is going to be another incentive for the industrialization and corporatization of livestock markets.”

The perspective from California’s large dairy farms is sharply different. “Dairies work on milk economics, not gas economics,” said Michael Boccadoro, executive director of Dairy Cares, a coalition of California dairy farmers. “You can’t simply add cows to make more gas.” What you can do, Boccadoro said, is limit the damage from the gas getting created. He argues that California has created a national model for that.

A recent tour of the World Energy plant in Paramount highlighted how the state’s bid to remake transportation fuels can work when things fall into place as planned. The facility, in the midst of a $1.5-billion conversion, is making jet fuel entirely out of animal fat, known as tallow. It comes from as far away as Australia and arrives on rail cars that pull right into the property. The tallow is unloaded into a giant storage tank that once held fossil fuels.

Tallow gets high scores from the state for climate friendliness in its ranking of ingredients that go into biofuels. It is a meat-industry byproduct with few other commercial uses. A demonstration by refinery officials of the jet fuel made from it showcases a liquid that is clearer, less odorous and cleaner-burning than the conventional stuff.

What stands out in Paramount is how much the refinery looks as it did when it processed crude oil. The facility’s infrastructure has not changed that much. Most of the machinery used to make diesel and traditional jet fuel also works to make the “renewable” jet fuel and diesel the refinery sells now.

When complete, the Paramount operation will process more than tallow. There won’t be enough of it to supply all the refineries — moved by California’s climate incentives — switching to next-generation renewable fuels in the coming years. Many refineries will ultimately be reliant on more easily available but less climate-friendly soybean oil and other such products.

The question is whether there will be enough of even that to go around.

Climate credits sold to California polluters bring billions to landowners. But scientists ask if that’s an environmental investment or a Ponzi scheme.

The demand for renewable fuels is projected to grow 800% from 2020 to 2030, driven in large part by California, according to Rabobank, an international bank that focuses on agriculture. It advises the amount of soy oil that could be required by all the renewable refineries set to be online soon, “assuming they are all built and soybean oil is the feedstock, would exceed the supplies of soybeans and soybean oil in the U.S.” Even small changes in supply, the firm warns, can create big swings in price.

It is all unnerving to some of the nation’s biggest food manufacturers. Companies are already struggling with supply chain stresses and inflation, with some starting to field calls from suppliers who can’t fill their orders, according to Robb MacKie, chief executive of the American Bakers Assn.

Prices for soybeans have already soared nearly 40% this year, with the war in Eastern Europe choking supplies for sunflower oil, a popular alternative for bakers. Nearly 80% of global sunflower oil exports come from Russia and Ukraine. The association wants California and the federal government to hit the pause button on some of their plans.

“It has not gotten to a critical point yet, but it could very quickly,” MacKie said. “These are government edicts that are diverting soybean oil out of the food supply.”

The scale of that diversion is highlighted by a pair of massive refinery conversions taking place in the Bay Area, one at the facility owned by Marathon in Martinez and the other at the Rodeo refinery owned by Phillips 66. Both dwarf the Paramount operation.

“This enables us to be part of California’s energy future,” Nik Weinberg-Lynn, manager of renewable projects at Phillips 66, said as he stood in the shadow of massive refining equipment that will ultimately generate more than a billion gallons of renewable fuels per year, making it one of the world’s largest such operations. “We’ll be taking fats, oils and greases and turning it into a lower carbon-intensive transportation fuel.”

Beyond seeing financial opportunity, fossil fuel companies that long resisted the shift away from oil are now seizing on California’s program to overhaul their image. The sprawling Phillips operation that refined crude oil for more than a century is being rebranded “Rodeo Renewed.” The company promises that the fuel generated there will reduce greenhouse gases equivalent to taking 1.4 million cars off the road each year.

The target market for the fuel is big trucks and heavy-duty agricultural equipment. The fuel Phillips will make can be swapped in for traditional diesel, without the need for any engine conversions or worries about warranties being voided.

The refinery is so big that seeing all of its various units in one morning requires a shuttle van. At one point the van stops at a largely vacant expanse of property dotted with a few massive storage tanks. Weinberg-Lynn points out that more biofuel units will be built there, towering 10 stories high. Down at the refinery’s marine terminal on the Carquinez Strait, the giant cargo ships filled with crude will be replaced with ships carrying edible oils and fats from around the world.

Many climate activists are skeptical these conversions will generate environmental benefits on the scale fuel companies and the state of California project. One of their biggest worries: All that soybean oil no longer available to food manufacturers could be replaced in part by palm oil from Asia, the production of which has long been linked to environmental degradation.

“It involves not only deforestation, but the release of greenhouse gas from the destruction of peat in palm oil plantations,” said Nikita Pavlenko, the fuels team lead at the International Council on Clean Transportation. “Those emissions could totally cancel out the climate gains created by use of biofuels.”

While many activists see significant potential climate benefits in California’s experiment, their underlying worry is the program will get hijacked by big energy and agriculture companies, and ultimately will be guided by their economic interests over California’s climate targets. The activists are urging regulators to leave themselves flexibility to adjust as needed, and not get locked into a subsidy system that later undermines advancement of greener forms of energy.

The Air Resources Board is trying to weigh all these considerations as it sets its incentive structures. It is fraught work. The agency’s staff has already come under withering criticism from an influential coalition of environmental justice groups after rejecting their petition to cut off the incentives for methane.

Activists wrote that the state considers only the manure, while overlooking “emissions generated formulating that manure.” That includes the food and water that cows and pigs consume, fuel burned in trucking the animals and animal products to farms and warehouses, and energy consumed by operating the barns and running milking machines. And there is also the tremendous amount of methane animals create through their burps, which doesn’t get captured by digesters.

The activists say the state should be mandating methane reductions, rather than paying for them. “That complete failure to regulate now lets facilities come back and say all this methane will go into the atmosphere unless you pay me to capture it,” said Tyler Lobdell, a staff attorney at Food and Water Watch.

Dairy Cares counters that mandating installation of multimillion-dollar digesters without any funding would be reckless. “Dairies would have simply fled California and produced methane somewhere else,” Boccadoro said.

The controversy was further stoked by a UC Davis study that found that California’s policy has made manure so valuable that it now accounts for more than a third of the revenue generated by dairy cows in many industrial-size facilities.

“A cow might make $5,000 worth of milk a year, and it makes about $3,000 worth of manure,” said Aaron Smith, a professor of agricultural economics at the university. “And so if you look at the economics of that, you’d say, maybe I should get some more cows and generate some more manure.”

While Smith said the data do not show — yet — that farmers are increasing and consolidating their herds to boost methane profits, many activists say they have seen enough.

Standing at the fence line of a large dairy near Merced, Madeline Harris, a regional policy manager for the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, ticks off a litany of effects big dairies are having on farmworker communities, including odor, water quality problems and toxic air. The state’s program, she said, “doesn’t address the impacts that dairies are causing to local communities, and it just incentivizes further growth.”

The state has been challenging those claims. “It is difficult to determine whether or to what extent environmental credit revenues influence management decisions of American dairy operators,” Stanley Young, a spokesman for the Air Resources Board, said in an email.

“Consolidation of these facilities has been occurring across the U.S. since prior to the adoption of [the Low Carbon Fuel Standard] and other incentive programs, and is driven by factors including milk production costs and farm efficiency improvements, changes in commodity prices, and demand.”

Back at the cluster of dairy farms near Bakersfield, the 500 cows crammed into one of the barns were chowing down on their breakfast and dropping pound after pound of poop as they ate. They stood in what amounted to a giant toilet, with water flushing the excrement at their hooves through the barn and toward a 627-foot-long lagoon. Each cow drops an average of 65 pounds of manure daily.

As Neil Black, the California Bioenergy president, walked alongside the animals, he said that giant collection of manure is going to be there spewing methane whether the state helps farmers keep it out of the atmosphere or not.

These large operations, he said, were already in place before his company built methane digesters on them and they would be doing a lot more damage to the planet if the state had not stepped in with biogas incentives.

“Other states should be learning from California,” he said. “They’re putting a price on carbon and that’s essential to being able to help … prevent the catastrophe of climate change that is right in front of us.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.