Democrats want a voting rights overhaul. Why are they pursuing rival paths to get there?

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Democrats are holding out hope for a national voting overhaul, a top priority and crucial piece of strategy for the party and the Biden administration. But they are running out of time to get it done, with redistricting looming and Republicans pushing new state-level voting restrictions.

Two rival voting rights bills are up for consideration in the Senate: the For the People Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Act.

Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) said he would bring the For the People Act to a vote next week. With the clock running low and margins looking slim, here’s a look at the differences between the bills and where each stands.

What do the bills do, and what is the difference between them?

Although the two bills are often lumped together, they are very different measures.

The For the People Act is ambitious and broad. It would create uniform federal election rules for all 50 states, preserving early voting, voting by mail and same-day registration.

Additionally, it would revamp the Federal Election Commission, require states to establish independent redistricting commissions, and implement a national voter registration system. Any voter could opt out of being registered, but otherwise, the system would automatically register people by pulling information from preexisting government databases, such as state driver’s license records.

There are also a few things in the bill that aren’t immediately related to voting rights and access. It would expand rules surrounding lobbyist disclosures and make several changes to ethics rules across all three branches of federal government. Most notably, the For the People Act would require a code of ethics for the Supreme Court and would require presidential nominees to release their tax returns.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Act, on the other hand, is a fairly narrow piece of legislation. Named for the late congressman and civil rights hero who fought for equal access to the ballot, it would strengthen portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, creating a pathway for new voter laws to be challenged in the courts and requiring “pre-clearance” again for a variety of changes to state and local elections procedures.

What is pre-clearance?

Pre-clearance is a process that was originally required by the Voting Rights Act for certain states and counties that had a record of racial discrimination, mostly in the South. It mandated that if these entities wanted to change certain aspects of their voting laws, they needed approval from the Department of Justice or the D.C. District Court to ensure the changes wouldn’t impede protected populations’ abilities to vote.

The rule applied to changes in polling locations, the times people could vote, requirements on what voters needed to show at the polls and, as Christopher Anders of the American Civil Liberties Union puts it, anything that “would change how it is that somebody could vote.”

Pre-clearance stayed in place in the United States for nearly 50 years, but it was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013. The court said that the United States had made progress on racial issues since the 1960s, making it unconstitutional for the federal government to monitor only certain states and counties.

“The Supreme Court said the problem with the old formula was that it was too old, and that it was based on old and outdated data about which states had a current problem with racial discrimination and voting,” said Richard Hasen, an elections law expert at the UC Irvine School of Law. “The John Lewis bill would try to remedy that by coming up with a new formula.”

By requiring pre-clearance for all 50 states, the John Lewis Voting Rights Act aims to sidestep concerns that some places are treated differently than others.

How did these bills originate?

The For the People Act was written in 2017 by Democrats and was widely considered to be a political messaging bill and a response to President Trump that had no chance of passage as long as he remained in the White House.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Act is a few years older. It was first introduced as the Voting Rights Amendment Act following the 2013 Supreme Court decision to overturn pre-clearance requirements.

Why are they suddenly on the front burner?

For starters, Democrats control Congress and the White House. Republicans have been less interested in beefing up voting rights.

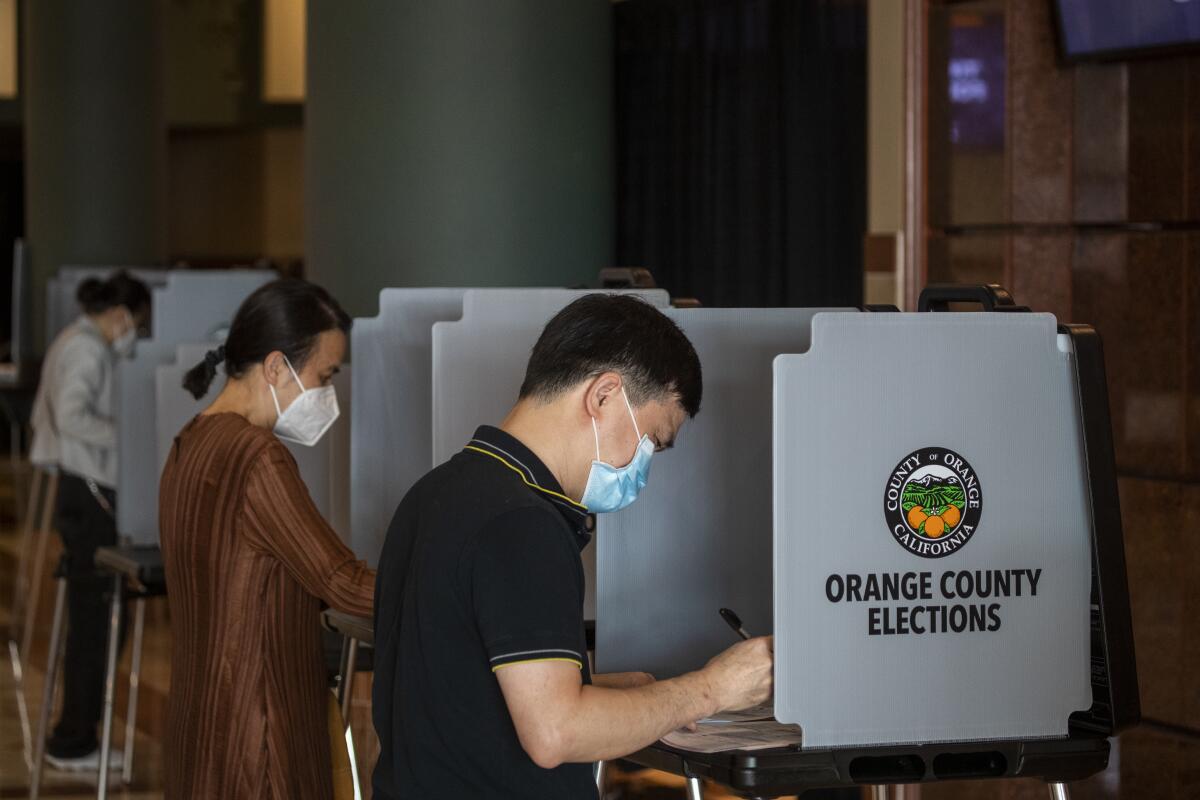

Also, the COVID-19 pandemic changed how Americans voted in the 2020 general election. More people voted early and by mail than ever before, and the For the People Act would preserve and standardize those processes.

Democrats also fear that changes being sought by Republicans could tilt the playing field in the GOP’s favor and disproportionately affect voters of color, creating a sense of urgency around protecting voting rights.

President Biden described a recently passed Georgia law as “Jim Crow in the 21st century” and a “blatant attack on the Constitution and good conscience.” He also asked Vice President Kamala Harris to lead his administration’s push to safeguard voting rights.

How would these bills affect state-level Republican efforts to limit ballot access?

Republicans recognize they were hurt in 2020 by early voting and mail-in ballots, so many Republican-led state legislatures have passed or are considering new laws that would curtail such options. There are only two states, Vermont and Delaware, where Republicans are not pushing new voting restrictions, according to a database compiled by the Brennan Center for Justice.

The For the People Act could override state voting restrictions in competitive states such as Georgia, Florida and Arizona.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Act wouldn’t have the same direct impact. Anders said changes that are already in effect can’t be undone by the bill because “it doesn’t go backwards.”

However, if it passed, the pre-clearance requirement could apply to future laws that attempt to restrict voter access. Given that there are nearly 400 restrictive bills currently under consideration in state legislatures and that the Justice Department announced plans on Friday to double its voting rights enforcement staff, that provision is significant.

With Democrats in control, aren’t chances for passage good?

Not necessarily.

The For the People Act already passed in the House. But in the Senate, it is on shaky ground, unlikely to garner the 60 votes needed to break a Republican filibuster and pass.

Not even all Democrats are on board. Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) said last week in the Charleston Gazette-Mail that he would not support the legislation, calling it “partisan.”

The John Lewis Voting Rights Act stands a better chance. Although the bill is not expected to be introduced until later in the summer, Manchin and Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) have said they will support it in the Senate.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said last week that the legislation is “unnecessary” and that he would not support it. The bill previously died in committee in the Senate after passing the House in 2019.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.