Analysis: How the Supreme Court has tilted election law to favor the Republican Party

The court has freed Texas and other Southern states to add voting restrictions, and has given the GOP an edge in the battle to control Congress.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — This year’s wave of new voting restrictions across the South may seem a response to the 2020 election, but its origins stem in no small part from the Supreme Court, which over the last decade has reshaped election law to elevate the power of state lawmakers over the rights of their voters.

The sum of the court’s rulings on elections could give the Republican Party a significant edge as it seeks to recapture control of Congress in 2022 and the White House in 2024.

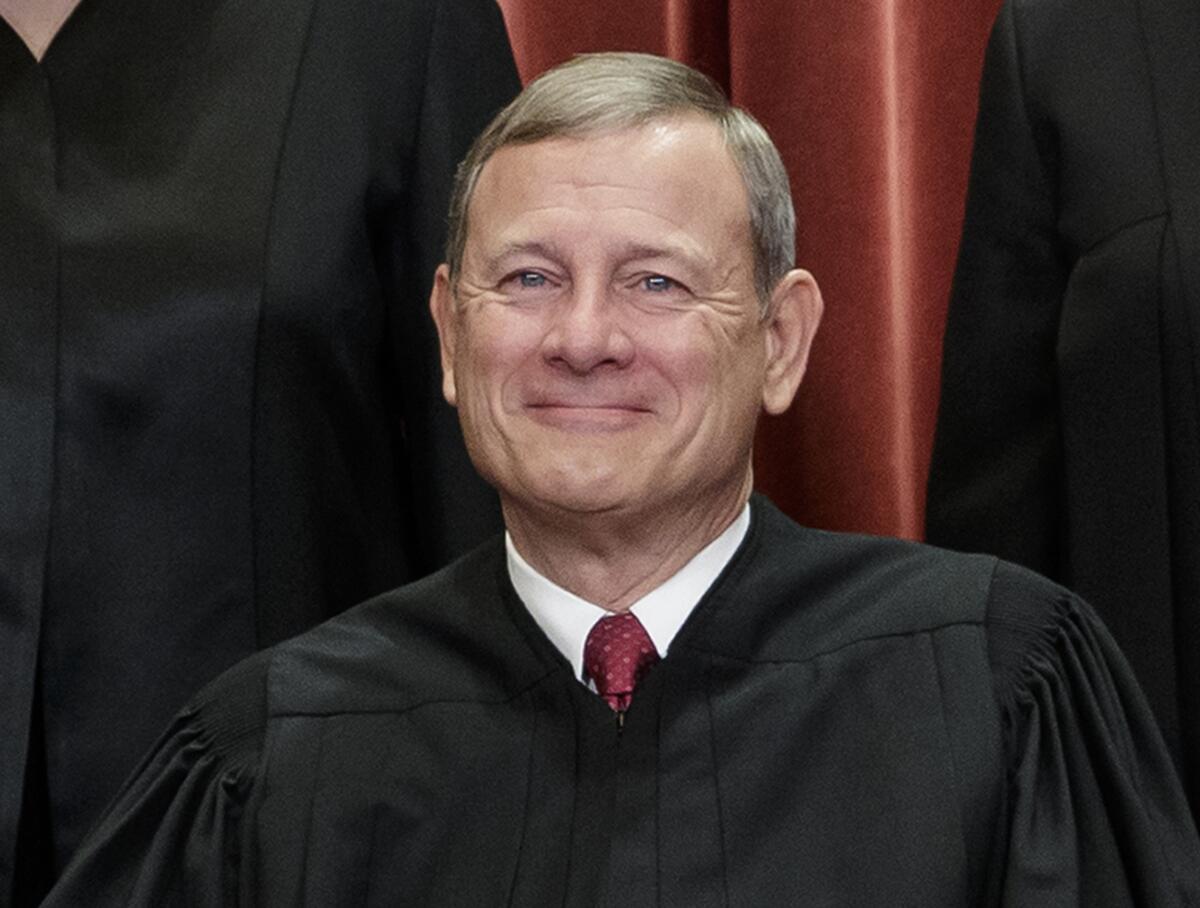

Under Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., the Supreme Court threw out the part of the Voting Rights Act requiring states with histories of discriminating against Black voters to clear election rule changes with the U.S. Justice Department. Writing for a 5-4 majority in 2013, Roberts called the section outdated and said it did not fit with “current conditions.”

The Constitution in the view of the Roberts court also allows lawmakers to draw gerrymandered districts to keep themselves in power, forbids limits on how much wealthy donors and incorporated groups can spend on campaigns and may even permit state lawmakers, not the voters, to decide who will be the president.

It’s a view that proved helpful to Republican-leaning states in skirmishes ahead of last year’s election and cleared the way for the recent showdown over the Texas GOP’s sweeping efforts to enact voting restrictions.

Biden asks Vice President Kamala Harris to lead his administration’s efforts to protect voting rights as many states work to add restrictions.

The court’s redistricting decisions alone could be enough to shift control in the U.S. House next year, according to Michael Li, a scholar at the Brennan Center. This will be the first cycle of redistricting in more than 50 years in which the Southern states may put their election maps into effect immediately.

“The Supreme Court has given a green light to aggressive partisan gerrymandering,” he said. “It is almost certainly enough seats in those states alone for Republicans to win back the House.”

Stanford Law professor Nathaniel Persily said he would be surprised if newly enacted voting restrictions are struck down. “The Supreme Court has not sent a signal they will protect the right to vote,” he said.

During the civil rights era of the 1960s and for some time beyond, the Supreme Court spoke of voting as a fundamental right, one judges had a duty to protect.

“The right to vote freely for the candidate of one’s choice is of the essence of a democratic society, and any restrictions on that right strike at the heart of representative government,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in 1964 in Reynolds vs. Sims.

But the notion of a constitutional right to vote has faded, replaced by the court’s conviction that the power of state legislators trumps the rights of the voters.

Harvard Law professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos, who teaches election law, said he wouldn’t speculate about the intent of the justices. “But across the right to vote, redistricting, the Voting Rights Act and campaign finance, the court’s decisions have benefited Republicans,” he said. “And partisan advantage explains these decisions better than rival hypotheses like originalism, precedent, or judicial nonintervention.”

State lawmakers versus judges

Last fall, the court’s conservatives repeatedly chastised judges who in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic sought to protect voters, for example, by extending deadlines for mailed-in ballots. A judge in the crucial state of Wisconsin said ballots postmarked by election day should be counted even if they arrived a few days late. The Supreme Court disagreed, 5-3, in an October vote.

The Constitution gives state legislatures, not judges, the authority to set election rules, said Justices Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh in Democratic National Committee vs. Wisconsin State Legislature. “Legislators can be held accountable by the people for the rules they write or fail to write,” they added.

Yet Wisconsin may not be the best example of legislators “held accountable by the people.” The state assembly districts were drawn to favor Republicans so much that the GOP held 63 of 99 seats after the 2018 election, even though Democrats won a statewide majority and ousted Republican Gov. Scott Walker.

Six months earlier, the Supreme Court had thrown out a lower court ruling striking down Wisconsin’s election districts as an extreme partisan gerrymander.

Republicans did not invent gerrymandering. Democrats led the way in the past. But when Republicans won big in the 2010 midterm election, they drew election districts to lock in their party’s control. When challenged in court, the Supreme Court sided with the states over their voters.

Roberts spoke for a 5-4 majority in 2019 to uphold North Carolina’s Republican legislators whose gerrymandered map all but assured Republicans would hold 10 of 13 seats in Congress, even if Democrats won more votes statewide. “To hold that legislators cannot take partisan interests into account when drawing district lines would essentially countermand the Framers’ decision to entrust districting to political entities,” he said in Rucho vs. Common Cause.

How far would the Supreme Court go to uphold the power of the states over the wishes of their voters? That question may be answered in 2024.

When it became clear President Trump had lost his reelection bid to Joe Biden, some conservative analysts and Republicans in Pennsylvania suggested the legislature could appoint its own slate of electors, defying the verdict of the voters.

They cited Bush vs. Gore, the Supreme Court’s 5-4 ruling that ended a recount of paper card ballots in Florida, preserving George W. Bush’s narrow victory in 2000. “The individual citizen has no federal constitutional right to vote for electors for the President of the United States unless and until the state legislature chooses a statewide election,” the court said, adding that even then, the state could still take back the power to appoint the electors who ultimately choose the president.

No state legislature chose last year to appoint its own slate to the electoral college, but if the presidential election is very close in 2024, there is a growing chance one or more will try.

Dispute over the Constitution

The legal divide over voting and elections begins with a basic dispute over how to read the Constitution and American history.

As written in 1787, it gave voters a very limited role. Members of the House were to be chosen “by the people,” but state legislatures would choose their U.S. senators, appoint the electors who chose the President and set rules for elections.

But the Constitution has been repeatedly amended to broaden and bolster voting rights, including protections against discrimination based on gender and race.

The Warren court saw this evolution as putting the voters in charge of America’s democracy, but today’s conservative justices espouse “originalism” and focus on the words of the 18th century Constitution.

“It’s a very different court now,” USC law professor Franita Tolson said, much more deferential to the states, but also, she added, “they are privileging the status quo of 1787 when the electorate was mostly white men and ignoring the more egalitarian Reconstruction Amendments.”

The major ruling weakening the Voting Rights Act highlights the difference. Congress passed that law under the 15th Amendment, enacted after the Civil War to protect Black Americans from having their votes denied or their voting power diluted.

In striking down a key part of the law, Roberts wrote that the framers of the Constitution intended the states to keep for themselves “the power to regulate elections.”

Civil rights lawyers may still file suits under the Voting Rights Act and seek to prove that new restrictions discriminate against Black or Latino voters. But these cases are hard to win and may take years of litigation.

Republican lawyers say the Democrats and their allies have been making exaggerated claims about “voter suppression.” They argue that elections require rules and enforcing those rules is not the same as denying anyone the right to vote.

The Supreme Court in March considered an Arizona rule that calls for tossing out ballots cast in the wrong precincts. “Arizona has not denied anyone any voting opportunity of any kind,” said Washington lawyer Michael Carvin, representing the Arizona Republican Party. Going to the right precinct is the “usual burden of voting,” not an unfair rule that targets minority voters, he said.

Free speech (and money) protections

This fall, Roberts will surpass the 16-year tenure of Earl Warren. While Warren championed equal rights and voting, the Roberts court has repeatedly invoked its duty to protect the 1st Amendment rights of the wealthy and corporate groups to spend money on election campaigns. It struck down laws going back to 1947 that restricted campaign spending on the grounds they violate the right to “political speech.”

“Political speech cannot be limited based on a speaker’s wealth,” the court said in the Citizens United decision in 2010, because “the 1st Amendment generally prohibits the suppression of political speech based on a speaker’s identity.” In that case, the “speakers” were corporations and incorporated groups. Unions won too because they had been restricted by the same laws.

“There is no right more basic in our democracy than the right to participate in electing our political leaders,” Roberts wrote four years later in the opening line of McCutcheon vs. FEC. The 5-4 decision in favor of the National Republican Committee erased the limits on total contributions to candidates.

This time, though, Roberts seemed to take the opposite view about whether legislators could be held accountable by the people when overseeing election laws: “Those who govern should be the last people to help decide who should govern,” he wrote.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.