How baseball saved an Iran hostage, not once, but twice

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The early April afternoon was perfect for baseball, sunny and cool. Even with the New York ballpark nearly empty, it all felt good and familiar to Barry Rosen: the food, the sounds, the smell, the hapless Mets, Jacob deGrom looking masterful on the mound even as fans warily eyed the bullpen.

Listen to the story:

As he took his seat, the 77-year-old felt a special joy at baseball’s return, after its COVID year without fans. That’s because, he says, the game saved him, not once, but twice.

Four decades ago, Rosen was one of 52 Americans held hostage for 444 brutal days in Iran. Not long after their release in January 1981, Rosen and the other hostages received a rare gift from Major League Baseball, a “golden ticket.” Signed by then-Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, under the words “In Gratitude And Appreciation,” the brass lifetime pass entitled each hostage and a guest admittance to any regular-season game.

It was a kind gesture — thanking Americans with the all-American pastime. But how could league officials have known what baseball meant to Rosen? It was that lifetime pass that got Rosen into Citi Field on that recent April afternoon. And it was baseball that helped him survive his captivity and rebuild his life and reconnect with his family.

“Baseball rescued me, us, and continues to,” Rosen said. “There is something beautiful about the game. It’s slow. It’s open. Wide open. You can watch the birds and still concentrate on what is going on. It was peace. It’s still peace.”

Rosen, who has a bald head, thin gray goatee and hazel eyes, grew up in Brooklyn, the youngest son of a diehard Brooklyn Dodgers fan. The boy and his father listened to games on the radio. When they grew older, they watched some on TV. When his dad, an electrician, had enough money, he took Rosen and his older brother to watch games at Ebbets Field.

“Those were wonderful times with my father,” Rosen said. “Seeing Duke Snider and Monte Irvin play, it was just the golden age.”

Rosen played stickball and youth baseball and dreamed of being a big leaguer despite not being that great a hitter. His parents pushed him in school, and he eventually got a political science degree from Brooklyn College.

He joined the Peace Corps and was sent to Iran, where he fell in love with the culture and people. When he returned to the U.S., he enrolled in Columbia University and obtained a master’s degree in Iranian and central Asian studies.

In 1978, he joined the State Department and was assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Tehran as its press attache. He left behind his wife, Barbara, 2-year-old son Alexander and infant daughter Ariana. The plan was for Barbara and the kids to join him.

But by then, the Iranian Revolution was in full swing. Iranians were becoming increasingly disenchanted with the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the nation’s autocrat leader who was backed by the U.S. government, known by militants as the “Great Satan.” In January 1979, the shah fled for Egypt.

The next month, the U.S. Embassy was stormed and taken over by militants who threw Rosen against a wall and beat him. The nightmare ended after just a few hours when the provisional government succeeded in securing the building and expelling the extremists.

Rosen and other diplomats were sent home. A few weeks later, the State Department decided to send a small team back to Iran. It was a risky assignment, but Rosen volunteered, believing he could do some good. He again left his family behind.

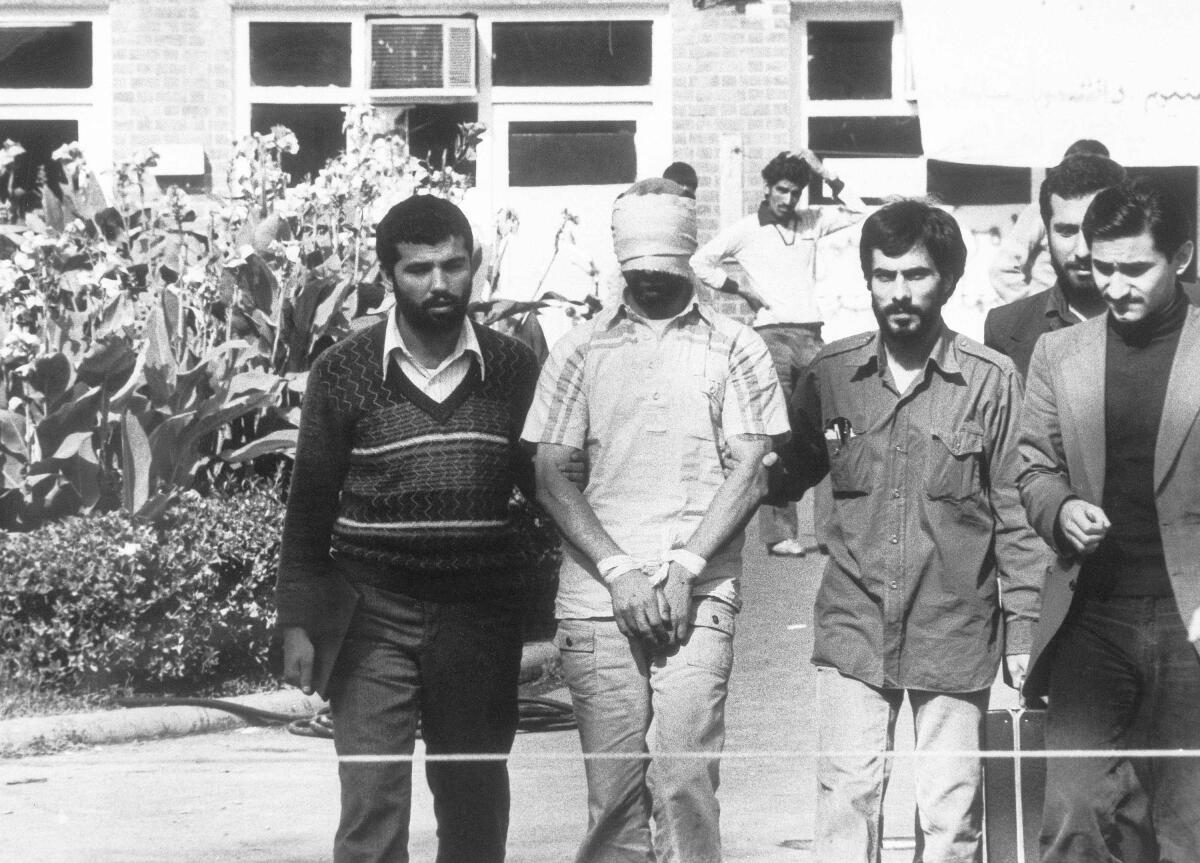

On Nov. 4, the embassy was again overrun, this time by students angry that President Carter had allowed the shah to enter the U.S. for medical treatment. Rosen and dozens of others were taken hostage. This time, there would be no rescue.

For more than a year, Rosen and 51 other Americans were threatened, beaten and held in rough conditions, including in solitary confinement. They didn’t know if they would live or die. At one point, an Iranian held a gun to Rosen’s head and forced him to confess to being a spy. He lost nearly 40 pounds and couldn’t sleep. His only escape was baseball.

For hours, he would sit and meditate about going to Ebbets, transporting himself to the halcyon baseball of his youth. “Baseball kept me sane,” he said.

He fantasized for hours, re-creating games down to the pitch, the fans sitting next to him and his father in the right-field stands, the lunches his mother packed them. He especially enjoyed his detailed replays of Carl Furillo — the “Reading Rifle” — handling caroms off the wall and firing balls home, for an out.

“It was the way to calm myself down and try to get into another world and the world of my childhood,” Rosen said. “We were always with my father. My father was a very endearing figure, a very wonderful man, and I just enjoyed being with him and knowing that I was always safe with him, and baseball did have that sense of safety for me — that was something that I loved as a little boy. And I never grew out of it.”

One day, perhaps four months into confinement, he was given 20 minutes by himself in a small courtyard. He hadn’t seen the sun since Nov. 4. The courtyard had a small patch of grass. It was so perfectly green, just like the outfield at Ebbets, an image he held onto over the rest of his captivity.

“How many times do you get the opportunity to escape from prison in your mind, and that grass did it,” he said. “I needed those 20 minutes very, very much. It helped me get through the next year. I would think back to that grass and baseball.”

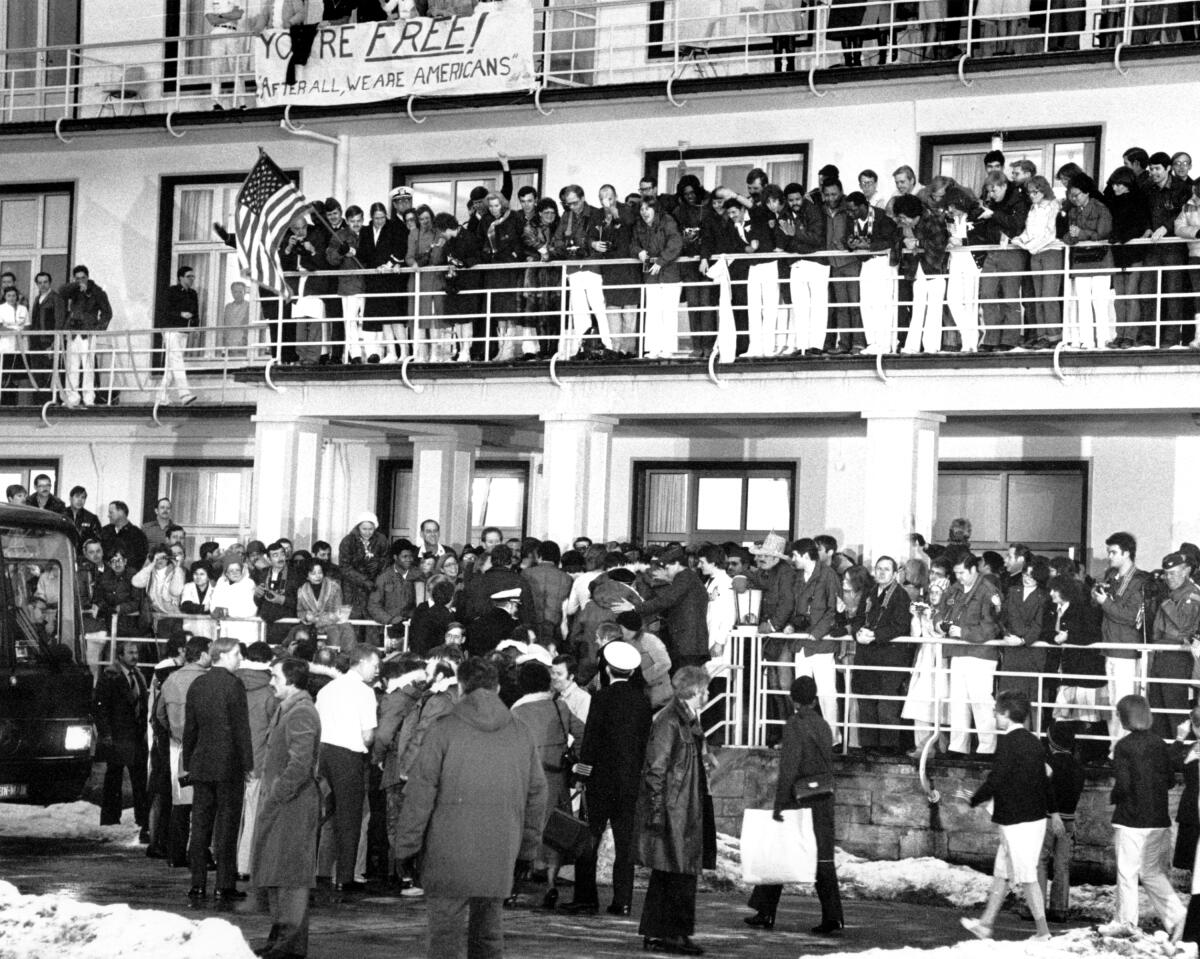

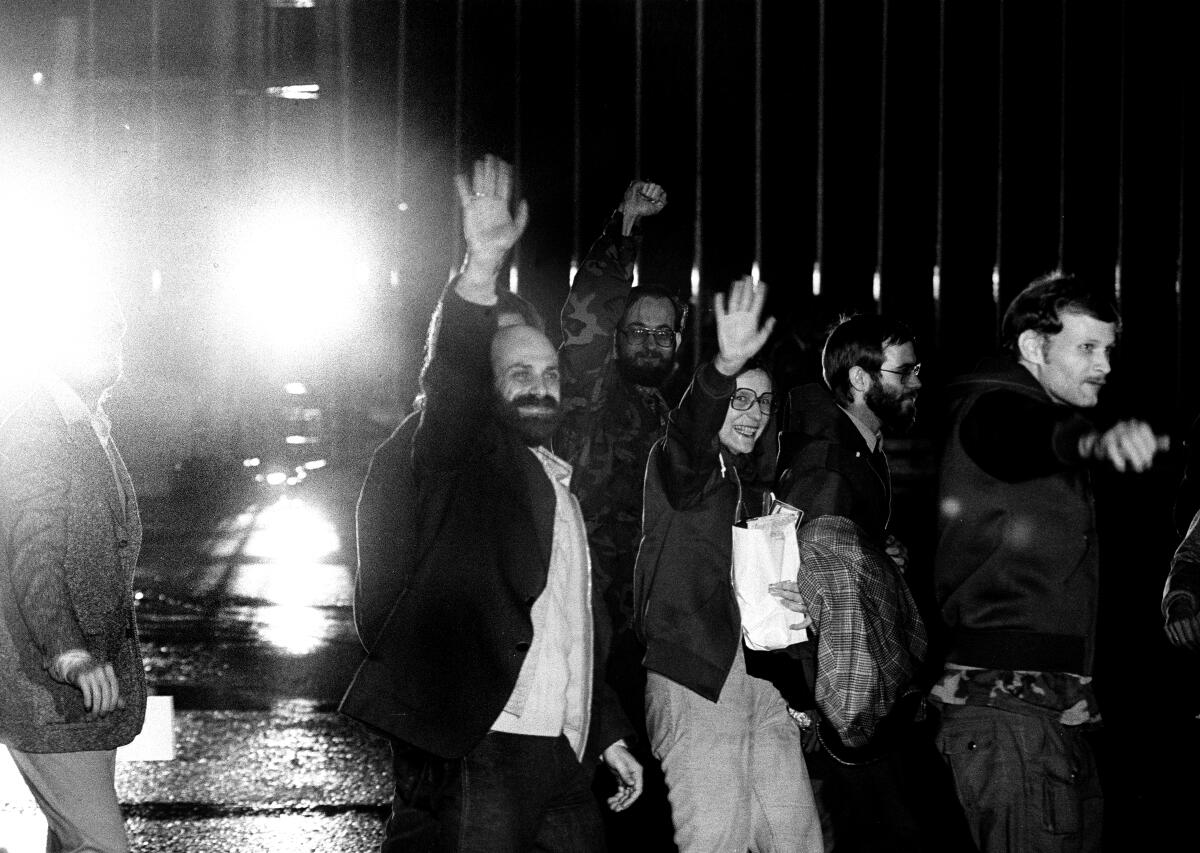

When he and 51 others were released, they were flown to Germany, where they spoke with therapists and officials. But Rosen felt he didn’t get the help he needed. He was clearly suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, he says, and struggling with how to cope with freedom.

When he got off the plane, he recognized his wife, but not his kids, whom he hadn’t seen in nearly two years. “Alexander was a little man,” he said. “Ariana was no longer an infant; she was a toddler.”

They returned to the family’s first-floor apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where Rosen tried to keep busy. He and Barbara began working on a joint memoir. He gave speeches. He tried to be a father, but his children were too scared to join him on trips alone outside the house.

“They were afraid he would leave again,” Barbara Rosen recalled, “that he would just leave for another two years.”

“They didn’t trust me,” Rosen said.

Like all the hostages, the Rosens were showered with gifts — a new vacuum cleaner, hundreds of coupons to a local restaurant, a Persian rug. One day, he opened a letter from Major League Baseball. It contained the lifetime pass. The gesture was a rare one from baseball, which has typically reserved such passes for U.S. presidents and longtime major leaguers.

At first, Rosen didn’t recognize the gift for what it could do. For that, he owes Barbara, who one spring day turned to her husband and said, “Take the kids to a baseball game.” A few days later, Rosen and his two children drove to Shea Stadium.

Over the course of the 1981 season, Rosen took Alexander and Ariana to about 30 games. Day games. Night games. It didn’t matter. With his beloved Dodgers long gone to Los Angeles, Rosen now rooted for the Mets. The team treated Rosen like a rock star. He showed his pass and got great seats. The Mets let him bring both kids, and sometimes their friends.

“The Mets were so wonderful then,” he said.

Slowly, over the course of the season, the family bonded. Alexander and his dad talked baseball. “He had so many questions,” Rosen said. Ariana, much younger, came for the atmosphere, ice cream and flat RC Cola.

“You have someone that you know should be your father, that you should love, but it was uncertain because I hadn’t seen him in a long time,” said Alexander Rosen, 44. “Baseball was alone time, and it was in an environment where you were enjoying a common experience.

“Baseball gave our father back to us.”

Over the years, they kept going to games, as far away as Philadelphia and Boston. Rosen said baseball still helps him cope with the lingering trauma of his ordeal. Going to a game makes him feel free and good for a week.

And then came COVID-19. He tried to get into the games on TV, but it wasn’t the same as going to the ballpark.

When he heard early last month that the Mets were opening Citi Field to fans, he called an old friend and fellow hostage, John Limbert.

Together they made plans to attend the Mets-Marlins matchup on April 10. Rosen contacted the Mets’ customer service and received an email declaring the team was not honoring lifetime passes. The Mets later reversed that decision after being contacted by The Times for this article.

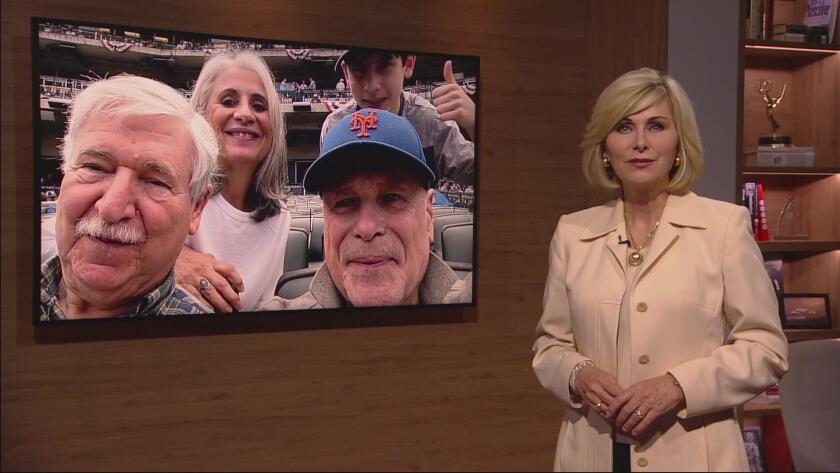

And so the pair of grizzled former hostages went to the park. Rosen brought Barbara. Limbert brought his 14-year-old grandson, Otto. Rosen wore a gray shirt and Mets hat. They ate hot dogs, burgers and drank soda.

It was a strange experience, being in a capacity-restricted game during a pandemic, Rosen said in a telephone interview from the game. The stadium was ghostly empty. No one sat near them. The crowd’s roar was more of a mewl.

Even so, it was all soothing and familiar, a return to normal. It was baseball and it cast the same spell it did when he returned to his family and country 40 years ago.

On the field were the same hapless Mets, who lost 3-0 despite deGrom throwing a gem. But Rosen didn’t care. Being among 8,419 in a ballpark, he said, was all that mattered.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.