Republicans in Congress to challenge Biden’s win Wednesday: What to expect

- Share via

WASHINGTON — At the urging of President Trump, Republican lawmakers on Wednesday plan to challenge Congress’ formal announcement of the 2020 presidential election results by pushing colleagues to exclude the results of several swing states, alleging without evidence that fraud should invalidate President-elect Biden’s victory.

Federal courts around the nation have concluded there is no evidence of large-scale fraud, and the lawmakers’ challenges are certain to fail.

But the unprecedented effort — seen as a last-ditch push by Trump to avoid becoming a one-term president — promises to turn what is usually a quick, constitutionally mandated formality into an all-night joint session of Congress that will give Trump’s supporters and his foes a final chance to square off over his presidency and the election.

Here’s a look at what to expect:

Wait, another challenge? I thought this was settled.

Yes, the election happened in November, when Biden won the popular vote and the majority of electoral votes in states. When members of the electoral college met Dec. 14 to cast their votes, they confirmed that Biden won 306 electoral votes to Trump’s 232.

But the founders added one final step for picking the president in the 12th Amendment: Congress counts and announces the results.

Jan. 6 is the day those electoral votes will be counted at a joint meeting of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

So what will this look like?

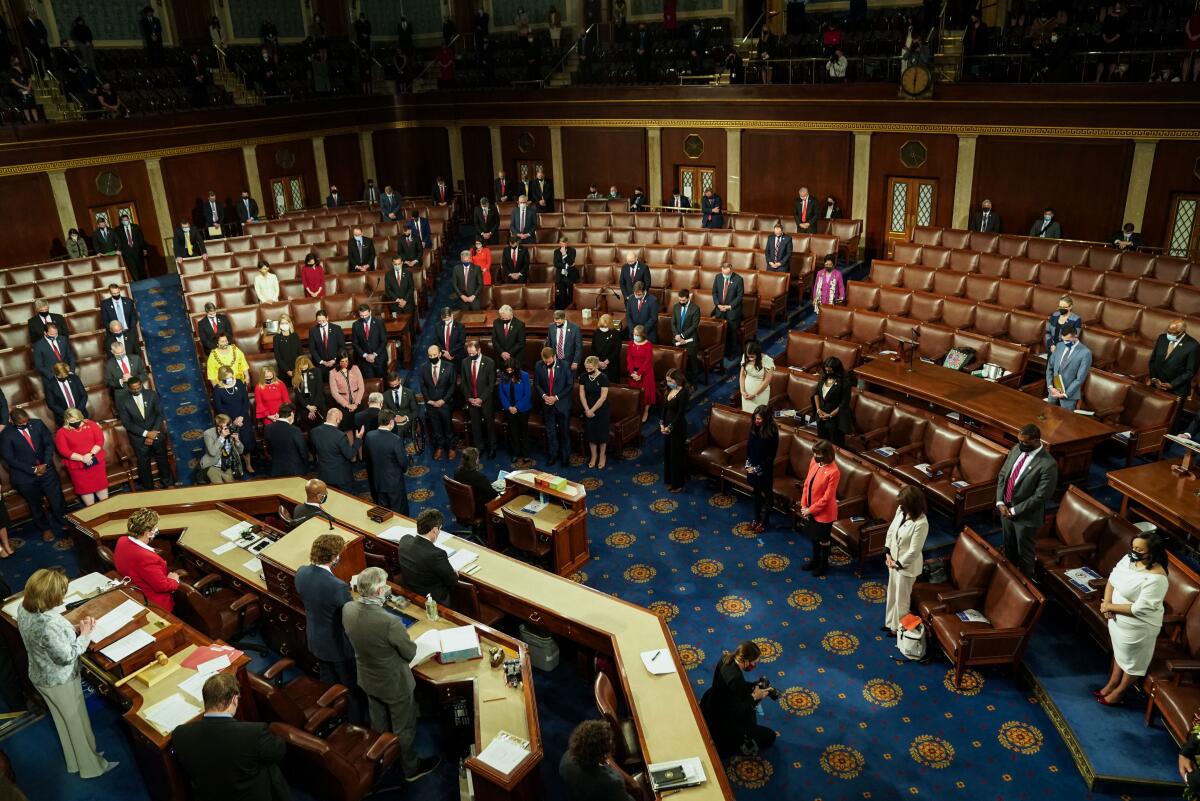

Representatives and senators are set to meet in the House chamber at 1 p.m. Eastern time.

The 12th Amendment orders the president of the Senate — currently Vice President Mike Pence — to present the certified results of the electors’ votes, which have been sent by each state and the District of Columbia. Two representatives and two senators, called tellers, then read the results aloud. No one else is allowed to speak.

In 1887, the Constitution was amended to allow lawmakers to raise objections during this process. So after the electoral votes of each state are read, in alphabetical order, Pence will ask if there are any objections. An objection must be submitted in writing and signed by both a representative and a senator to be considered. Lawmakers do not need to be from the state they are objecting to, and every challenge must be supported by at least one member from both chambers.

If an objection meets the required criteria, the House and Senate then meet separately for up to two hours of debate over whether to include that state’s results. Both proceedings will be televised. A majority of both chambers is needed for the objection to succeed. Otherwise the objection fails and that state’s votes are counted.

If the Senate upholds an objection and the House does not, or vice versa, the objection does not succeed and the votes are counted.

Democrats control the House and will have the ability to reject all challenges, likely with the support of some House Republicans. At least 20 Republicans in the closely divided Senate have indicated they will reject any challenges, dooming objections there as well.

So why are Republicans doing this?

Mostly because Trump has asked them to as part of his effort to falsely portray the 2020 election results as invalid. Most of the Republicans objecting are loyal Trump supporters who are eager to please the president and his base.

Some will argue that electors’ votes shouldn’t be counted because in some states election officials or judges mandated changes in the election rules to make voting easier or safer during the pandemic. They will argue that only state legislatures have the power to change election rules, not courts or bureaucrats.

Some in the GOP have joined Democrats in opposing the effort, saying it will undermine faith in the electoral process by making false claims about fraud and manipulation, and stressing that voters, not Congress, should determine the election result.

How long will the process take?

It depends on how many states are challenged and whether members use up the full time allowed to debate. Members who have said they will object to results have not said exactly what states they will target, but at least some of the six swing states that decided the election— Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Nevada— are the most likely candidates.

Traditionally, each representative and senator is allowed to speak for only five minutes, and the full two hours does not have to be used. But throw in COVID-19 restrictions on how many members can be present, disinfection of the chambers, and how long it takes to get senators to amble across the Capitol, and each objection could take three or four hours to debate.

We do know that Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) plans to join an objection to the Arizona results and will use his time to argue for the creation of a commission to review election results.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) has tapped Reps. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank), Zoe Lofgren (D-San Jose), Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) and Joe Neguse (D-Colo.) to lead the House Democratic response to the objections. Democrats from those states have also been told to prepare to defend their state’s electors during any debate, House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) told reporters this week.

It could be a late night, or it could be Thursday before all the votes are counted and Pence announces Biden and Harris as president and vice president.

What has this process looked like in the past?

It’s usually staid, boring and over fairly quickly. In 2017, it took 35 minutes.

Why were lawmakers given the power to object?

It was an attempt to smooth the process and allow disputes to be resolved publicly.

The first time the count of electoral votes in Congress was interrupted was after the 1876 presidential election, and the hubbub it caused led to the current process.

Democrat Samuel Tilden had emerged from the close election in the lead against Republican Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio. Tilden was just one vote shy of the 185 electoral votes needed at the time to win. However, 20 electors from Florida, Louisiana, Oregon and South Carolina were in dispute. When Congress met in early 1877 to count the electoral college votes, electors for both Tilden and Hayes claimed victory and submitted votes.

The Democratic-controlled House and Republican-controlled Senate created a commission to resolve the election. Following a lengthy process, a controversial deal was struck: Democrats agreed to award all 20 disputed electoral votes to Hayes, handing him the presidency, and Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South that had been enforcing civil and political rights of Black people, leading to the end of the Reconstruction period after the Civil War.

Unease about the Hayes compromise and a separate 1857 dispute over some weather-delayed electoral college votes from Wisconsin led Congress to pass the Electoral Count Act of 1887. That act set the procedures for formally objecting to a state’s electoral votes, and largely gave states the responsibility to resolve presidential election contests and challenges before they got to Congress.

Has this ever happened before?

Only twice since 1887 has Congress formally considered objections. Both times the objections involved a single state. Each failed, and the process was concluded in a few hours.

The first, in 1969, occurred when two Democrats objected to the vote of a North Carolina elector who was supposed to vote for Richard Nixon and instead voted for George Wallace. Congress determined state law allowed the elector to change his vote.

The second, in 2005, occurred when Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones (D-Ohio) and Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) objected to Ohio electoral votes over reported voter irregularities.

In several other instances, including in 2017, lawmakers from either the Senate or House have raised objections over a state’s results, but they were not joined by a member from the opposite chamber, so the objections were never considered.

The magnitude of the current effort, involving several states, is unprecedented, with dozens of House Republicans and at least a quarter of Republican senators saying they will either oppose the results or vote to uphold the objections.

Could Pence, as president of the Senate, simply announce Trump as the winner?

No. The Electoral Count Act of 1887 specifically bars the vice president from arbitrarily deciding to reject a state’s votes.

Votes can only be rejected if a majority of the House and Senate agree.

A federal appeals court recently threw out a lawsuit from Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-Texas) seeking to allow Pence to decide unilaterally.

Could Inauguration Day be delayed?

No. The date of the inauguration is set by the 20th Amendment to the Constitution, which moved Inauguration Day from March to January. Donald Trump is no longer president at 11:59 a.m. Jan. 20. If Congress has not counted the electors by that moment, the Speaker of the House becomes acting president until they do.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.