‘This is crazy.’ Trump’s push to reopen schools amid pandemic gets low grades from parents

- Share via

All Ciera Pritchett could do was laugh. She had just rung up her daughter’s elementary school, looking to see whether classes would be taught in-person or entirely online, and the response was confounding.

“’I’m sorry, I hate to say it, but I can’t tell you anything,’” Pritchett said she was told. Despite the coronavirus looming over the country all spring and summer, the Duluth, Ga., mother of two was stunned that public officials had no clear plan with just three weeks to go before the school year began.

Hence the chuckle as Pritchett, 34, summed up the situation: “This is crazy, really. It’s unbelievable what’s happening.”

Fellow parents may laugh; others want to cry or scream (perhaps all three). As the school year approaches, the country’s jumbled response to K-12 education in the coronavirus era has yielded pervasive dissatisfaction with the options — or lack thereof — for families with school-aged children. The frustrations reverberate all the way to the White House, as polling and interviews with parents across the country show widespread disapproval with President Trump’s gung-ho approach to reopening classrooms.

“It’s one of the most fundamental issues right now. Particularly for parents, this is the issue,” said Christine Matthews, a Republican pollster. “Trump can talk about defunding the police or Confederate statues, but I can tell you the No. 1 concern on the minds of parents is whether or not their kids can safely go back to school, and if not how are they going to get through the school year.”

Trump, who sees schools as key to revving up the flagging economy — and, not incidentally, boosting his reelection chances — has been unambiguous. He wants to start the academic year “quickly, beautifully” in person; districts that don’t, he warned, could lose their federal funding. He also blasted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidance to reopening as too burdensome. The agency released additional direction on Thursday, which emphasized the importance of in-person instruction and the low risks the virus poses to school-aged children.

Trump hedged his position slightly on Thursday, conceding that districts in current virus hot spots may need to “delay reopening for a few weeks.” Nevertheless, he added, “every district should be actively making preparations to open.”

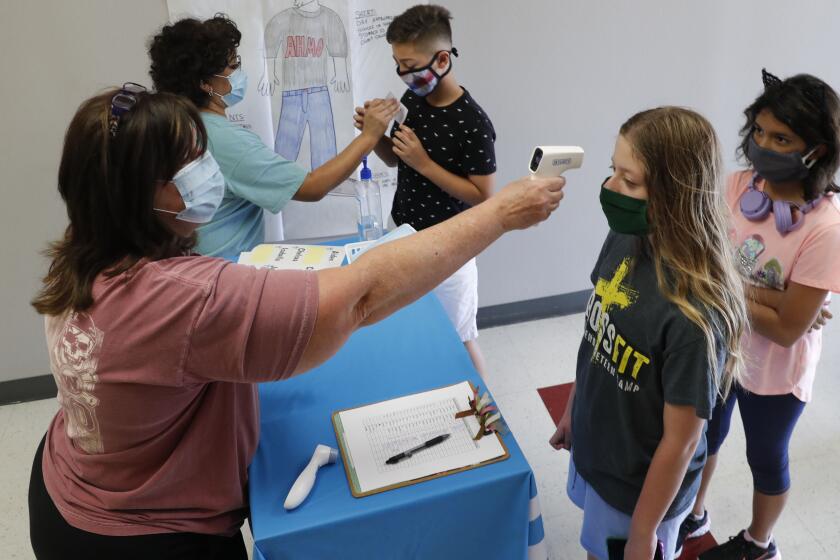

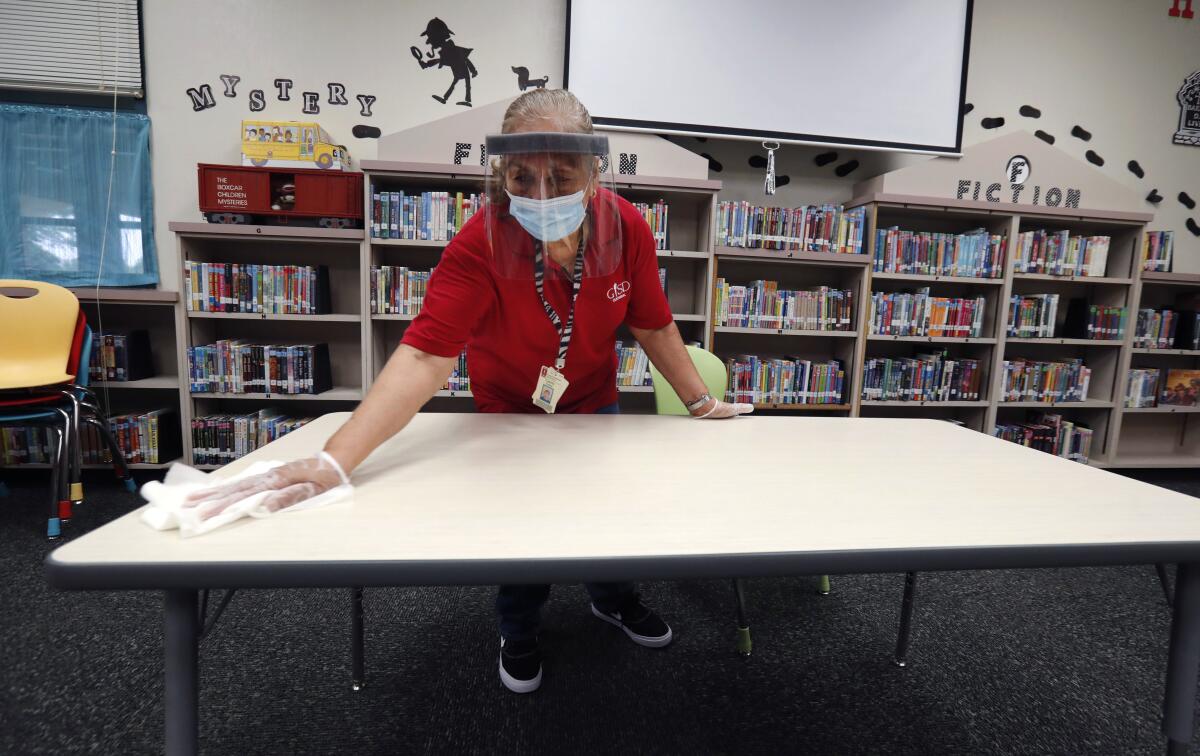

While Trump has staked a mostly hard-line stance, many parents, school administrators and health officials see a more complicated calculus. Research shows children, especially younger ones, largely do not get seriously ill from COVID-19, but their role in spreading the virus to adults such as teachers and other school employees, or family members back home, appears to vary by age. Other countries that have successfully opened schools did so when outbreaks of the virus were largely controlled, while the United States continues to see surging spread.

“We had a problem with overcrowding before COVID,” said Kimya Jacobs, who works for a nonprofit that encourages parent involvement in Detroit schools. The 42-year-old, who lives with her two adult daughters and three grandchildren under the age of 2, said she had a hard time picturing the schools ensuring students would wear a mask or socially distance. “How does lunch work? How does recess work?”

Here’s what scientists know about kids’ potential to spread the coronavirus and the risks of sending them back to school amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Parents and policymakers are weighing potential risks against the downsides of keeping kids at home, including developmental and socialization drawbacks, lack of access to school-provided nutrition and possible increased exposure to abusive household environments. For working parents, having children at home during the day could be an added challenge or downright impossibility.

Shannon Duckworth, whose two sons attend middle school in the St. Louis suburbs, said her district announced a hybrid plan that combined two days in-person instruction with virtual learning — a setup that could leave families scrambling for child care.

“It’s kind of depressing,” said Duckworth, 42, whose work as a freelance fashion consultant gives her more flexibility than many to supervise her kids at home. “It’s assuming a lot about the privilege of our area, the privilege of our families.”

Trump’s threat to withhold money rankled Tiffany Jones, a hospice nurse from Indianapolis. Juggling her administrative work from home and helping her son with his kindergarten classes was nearly impossible in the spring, but Jones, a 44-year-old cancer survivor, said she feared she could contract the virus from him if he went to school. She worried the school’s meal program, which continued to provide food for her son, could be at risk under Trump’s plan.

“I don’t agree with him cutting funding if schools don’t open,” said Jones, a member of ParentsTogether, a national advocacy group. “I don’t agree with that at all.”

Trump’s blunt position has fallen flat with voters, according to multiple polls. An Associated Press survey on Monday found the public disapproved of Trump’s handling of education issues by a 2-to-1 margin. Another poll by Quinnipiac University found that among Republicans, where the president usually commands near unanimous backing, just two-thirds of respondents approved his actions. His numbers cratered outside his party, especially among women: only 20% of independents and 3% of Democratic women backed the president.

The issue will likely exacerbate Trump’s floundering support among women, said Democratic pollster Celinda Lake, who noted that even white women, the majority of whom backed his 2016 bid, are moving away from the president.

“You do not want to get between moms and their kids,” Lake said.

The White House’s demand for reopening is a dramatic break from traditional conservative orthodoxy, which holds that education policy is generally best left to authorities outside Washington.

“You can’t have it both ways,” Matthews said. “Republicans have always been about local control. This is an enormous departure from that.”

Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, has offered his own spin on the schools issue, arguing that reopening plans should be tailored to local conditions. In an updated road map released last week, the former vice president proposed national safety guidelines based on the spread of the virus to inform decisions on the local level, and provides $30 billion in additional funding for protective equipment and alterations to school infrastructure.

Opinions don’t always match up neatly along party lines. Kenna Welch, a former teacher and stay-at-home mother of three, said a Facebook thread about schools in Oak Park, a liberal Chicago suburb, grew to 800 comments within 90 minutes, with many Democrats backing reopening so they could return to work.

“If you would think pushing your kids to go back to school is more of a conservative viewpoint, that’s not the conversation that was happening,” said Welch, 44, whose kids learn remotely. Still, when the tone of the social media debate got too heated, commenters would often turn their attention to Trump, a shared foil, to take down the temperature.

“People would always flip it back to, ‘We wouldn’t be in this position if we had some leadership at the federal level,’” she said.

“You do not want to get between moms and their kids.”

— Celinda Lake, Democratic pollster

Zach Biehl, a former youth football coach from Cumming, Ga., similarly faulted the Trump administration for injecting politics into an “agonizing” situation. While his family has chosen virtual schooling for their 14- and 12-year-olds, he said he didn’t blame parents for wanting in-person instruction.

“Our kids now have become pawns in it and that’s really sad,” said Biehl, 43, who identifies as a political independent and plans to vote against Trump.

The reviews for state and local officials have varied. Nearly 7 in 10 adults — including roughly 40% of Republicans — say they trust their governor more than Trump about how to restart the economy, a recent NBC News/SurveyMonkey poll found.

Jones, who voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016, gave high marks to Indiana’s Republican Gov. Eric Holcomb for “looking out for his community.” But Pritchett, a fellow ParentsTogether member, was more critical of her governor, Republican Brian Kemp of Georgia, who challenged the city of Atlanta’s face mask ordinance in court last week.

“I don’t think he actually cares about safety,” Pritchett said, with another incredulous laugh.

The issue will likely ripple further down the ballot. Duckworth said she plans to vote against her county’s executive, whom she believes has been overly restrictive by shutting down parks and recreational youth sports. But though she generally agrees with Trump on the need to open schools, she says his leadership has been lacking, making the issue more divisive than it needs to be.

“Is this a political thing or are we actually trying to solve a crisis that is going on in this country?” said Duckworth, a political independent with libertarian leanings. The schools issue would definitely weigh on her vote choice, she said; as of now, she remains “totally undecided.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.