As Congress leaves town, hopes for police reforms fade

- Share via

WASHINGTON — After George Floyd’s death in police custody, both Republicans and Democrats immediately wrote bills to change policing practices, sparking hope that they would overcome the partisanship gripping most policy debates to enact meaningful legislation.

But as lawmakers leave Washington for a two-week recess, the parties are locked in a bitter standoff with no meaningful negotiations planned and little hope of finding compromise as time on the legislative calendar grows short.

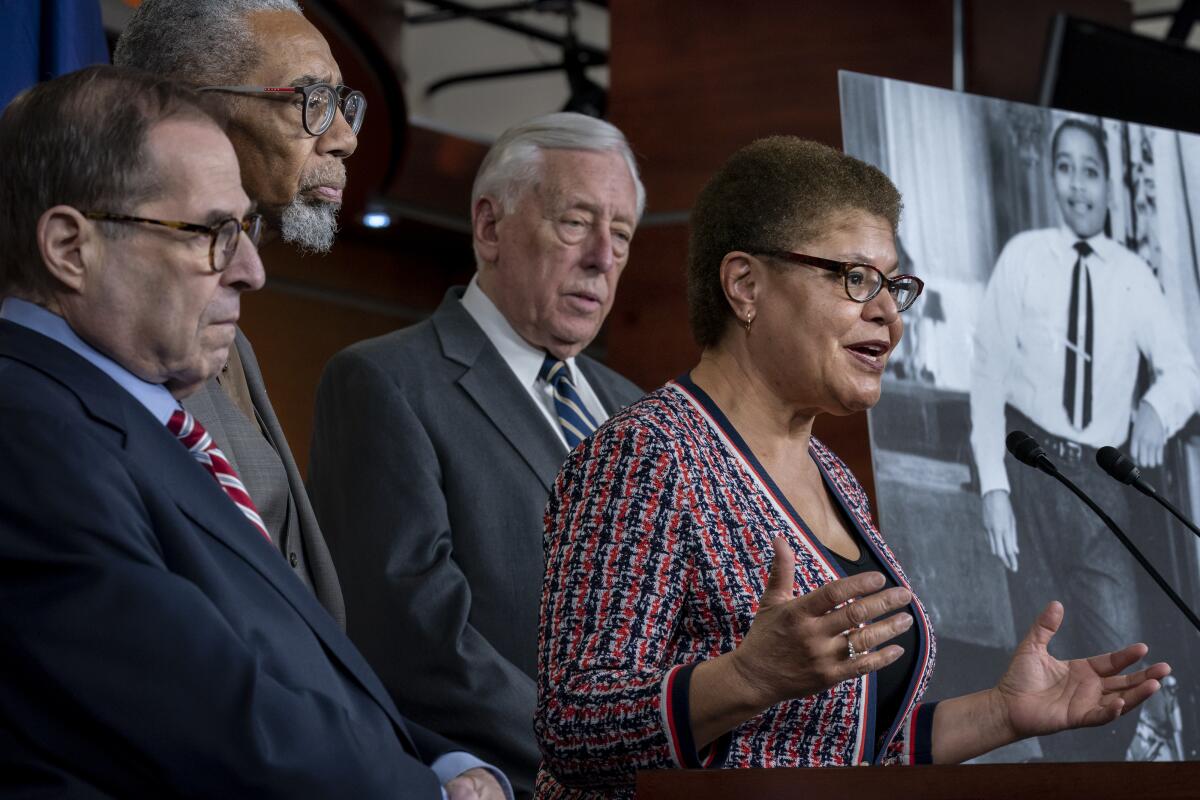

Rep. Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles), who led the effort for the House Democrats’ bill, and Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.), who did the same for Senate Republicans’ version, have continued to talk since the House approved its measure, 236 to 181, and Democrats blocked the Senate bill last week.

But there’s “nothing formal happening right now,” Bass said. Any talks are “just very informal.”

Bass expressed optimism, however, that lawmakers can find a way to push the legislation forward. She noted that some Republicans have shown interest in revisiting her legislation, which all but three Republicans opposed last week, while efforts are underway to pressure the Senate to take up the House bill.

“The movement for justice will not stop until the bill is passed in the Senate and signed by the president,” Bass said Wednesday. She spoke even as the Congressional Black Caucus turned its focus to a broader effort to end systemic racism through a series of bills that include proposed reparations for slavery.

An aide to Scott confirmed that the senator, who is the only African American Republican in the Senate, will continue the discussions. “We are not giving up, and will see where conversations over the next couple of weeks lead,” the aide said.

Privately, however, lawmakers and aides in both parties expressed little hope that compromise can be reached quickly, if at all.

Hundreds of bills approved by the Democratic-led House languish in the Republican-controlled Senate. The level of bipartisan and biracial furor over Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, after numerous deaths of other Black men in encounters with police nationwide, had led many Democrats and some Republicans to hope that on policing reforms they could surmount that partisan paralysis. But that hope quickly dissolved. Democrats dismissed Republicans’ proposals as window dressing, Republicans accused Democrats of federal overreach and President Trump threatened to veto the House bill.

Significant policy disputes emerged over banning chokeholds by law enforcement and whether people should be able to sue police officers if they believe their civil rights have been violated.

There is agreement on compiling data on police misconduct and sharing it across jurisdictions nationwide, as well as on making lynching a federal hate crime. But it is unclear whether the parties might be willing to merge those areas of agreement and pass a bill that doesn’t do everything both sides had hoped for.

“Instead of getting 75% last week, we’re at zero this week and we’ll head into the Fourth of July with nothing done. And that is a shame,” Scott said on CNN on Sunday.

Scott blamed Senate Democrats for blocking the GOP bill. “We cannot get something done if the Democrats in the Senate are more interested in presidential politics than they are in getting something actually finished this year,” he said.

Democrats in the Senate said the Republican bill had so many problems that it was not even an adequate place to begin negotiation. Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) said on the Senate floor that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) brought the Scott bill to the floor “not to solve the problem of police brutality in America but to solve his political problem,” given public support for changes.

Proponents of policing reforms are nervous that the momentum and the public’s interest in addressing policing practices may wane if Congress doesn’t act swiftly.

“It’s clear that the moment is now for us to get something done and we should not have to wait for a change in presidency,” said Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.), when asked whether legislation stands a better chance if Democrat Joe Biden is elected in November.

Yet time is running out in an election year. After the two-week recess, lawmakers are expected to be back for two weeks, mainly to work on legislation to further respond to the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Then comes their August recess, a break that during a presidential election year typically is viewed at the deadline for policymaking; by September lawmakers are eager to get home to campaign and reluctant to take a politically risky vote.

The “lame duck” session of Congress — the post-election period before a new Congress begins in January — could provide a last window of opportunity. Such sessions are unpredictable but sometimes offer lawmakers a chance to quickly enact legislation that is controversial but widely supported.

Times staff writer Sarah D. Wire contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.