The Supreme Court rejected Trump’s attempt to end DACA. Now what?

- Share via

WASHINGTON — A long-awaited Supreme Court ruling Thursday rejecting President Trump’s attempt to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program brought relief to thousands of DACA recipients — but also new questions about the administration’s immediate next steps and the still-uncertain future of “Dreamers” in the United States.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., speaking for the 5-4 majority, called the administration’s attempt to rescind the program “arbitrary and capricious,” violating federal procedural law. But he also wrote, “We do not decide whether DACA or its rescission are sound policies.”

For an administration that’s demonstrated an eagerness to restrict immigration, both critics and supporters say the narrow decision leaves room to try to delay new applications, renewals and work authorization — or attempt to end DACA again.

On Friday morning, Trump framed one of the biggest defeats of his administration, and on his signature issue, immigration, as essentially a “do over,” saying the administration will repeat its attempt to rescind DACA.

“The Supreme Court asked us to resubmit on DACA, nothing was lost or won,” he tweeted, seeming to question the justices’ patriotism. “We will be submitting enhanced papers shortly in order to properly fulfil the Supreme Court’s...ruling & request of yesterday.”

Trump, who in the past has expressed concern for the Dreamers, railed on Twitter against the Supreme Court’s decision on Thursday as “horrible & politically charged” and akin to “shotgun blasts into the face” of his supporters. But neither he nor any other officials indicated they’d act again on DACA before November, and Friday, he left open how and when.

León Rodriguez, former director of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the agency that administers the program and other immigration benefits, said the court’s ruling “requires them to take new applications” but doesn’t prevent Trump administration officials from “taking another shot” at DACA.

“I’m really worried that they will say, ‘Fine, we will protect you all from deportation, but no work authorization for any of you, there’s no legal basis for it,’” Rodriguez said. “These are folks who have driver’s licenses, they go to school, they work — to suddenly cross that out, even if all those folks still remain in the U.S., on many levels, individual, families, the economy, communities — it would make a huge mess.”

But with the 2020 presidential election just months away, it’s an open question whether the administration will want to take on DACA again, he said.

DACA has granted some 700,000 young people temporary protection from deportation and access to work permits since 2012, when President Obama announced it, until 2017, when then-Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions declared the program unconstitutional. DACA recipients, known as Dreamers, were brought to the country as children and passed background checks.

That includes some 27,000 healthcare workers on the front lines of the coronavirus crisis, and more than 186,000 Dreamers in California alone.

University of California President Janet Napolitano, who launched the DACA program when she was Obama’s secretary of Homeland Security, filed a lawsuit in 2017 against the Trump administration in federal court in San Francisco, along with California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra, arguing that the administration hadn’t given a valid reason for ending DACA.

Napolitano said Thursday in an interview with The Times that she’d been watching her phone at 7 a.m. every day for the last month for the DACA ruling, which she called “a bit of a surprise.”

“Having created DACA, I fully recognize that it would be possible — not reasonable — but certainly possible for another administration to say that they wanted to follow a different policy,” she said. “You can’t just do it and kind of unwrite the rules of the road that at its height some 800,000 DACA recipients are relying on with a one-line order, which is what they did.”

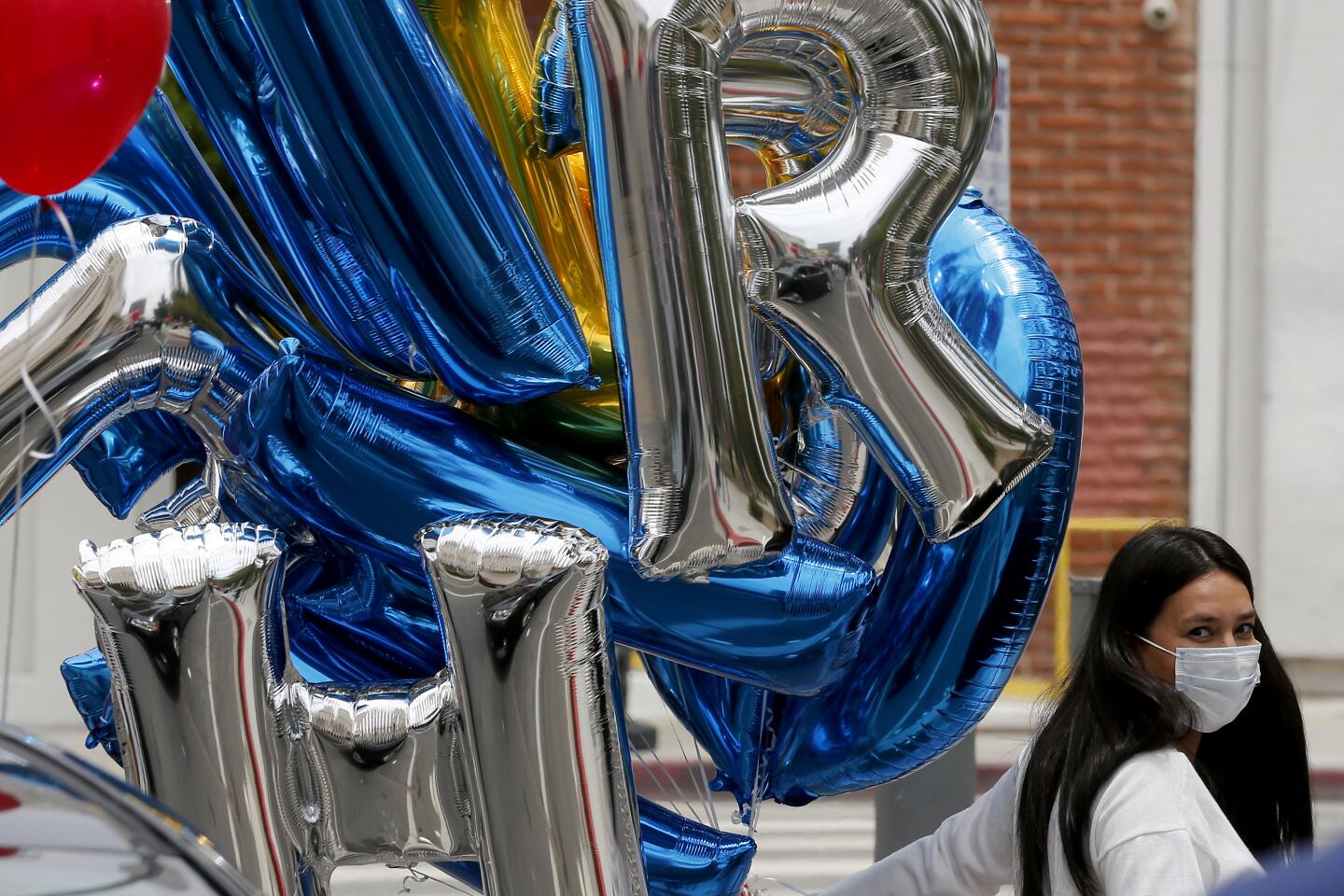

The Supreme Court’s decision saving DACA reinvigorated many across California, home to more DACA recipients, known as Dreamers, than any other state.

She said the Trump administration may try to deny Dreamers benefits or try again to rescind it, but added: “It’s not the kind of thing where you want to lose twice.”

Orders from lower courts in effect froze the program in September 2017 while the administration appealed directly to the Supreme Court. Though the administration was required to renew existing DACA applications, roughly 66,000 children have turned 15 since then, eligible for DACA but blocked from applying, according to the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute.

Officials at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS, told The Times on condition of anonymity late Thursday that they have yet to receive any guidance in the wake of the DACA decision, including whether or not they should restart processing new applications. The administration has also threatened to furlough thousands of personnel this month unless Congress gives the fee-based agency $1.2 billion, saying it is essentially bankrupt, though the cause and extent of the shortfall is disputed.

“How will they file new DACA apps if USCIS is shut down?” one official asked.

Mike Howell, a former Trump administration official in the Homeland Security Department’s Office of the General Counsel and a senior advisor at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, said administration officials should “stop issuing any renewal or work authorization” as they try to fix the procedural issues identified by the court and again rescind DACA.

“They were avoiding a politically contentious issue by calling a process foul,” he said of the justices.

But, he allowed, any renewed attempt to get rid of DACA just got a lot harder. And in the meantime, officials must take new applications and process renewals and work permits. “Absent any other affirmative action by DHS,” he said, “the program is operating as it initially was dreamt of.”

The Homeland Security and Justice departments did not respond Thursday to requests for comment, and neither did White House advisor Stephen Miller, the chief architect of Trump’s restrictive immigration policy, or the National Security Council.

Two top Homeland Security officials rejected the ruling in a statement, but didn’t signal next steps. Both are in acting roles, underscoring ongoing struggles with record vacancies at the department.

One, Ken Cuccinelli, a hard-liner with the official title of “senior official performing the duties of the deputy secretary of Homeland Security,” tweeted, “Terrible. Awful. Double-standard. Outrageous. Supreme Court says all any President needs is a pen and a phone? Does anyone think they’d let @realDonaldTrump just make up ‘laws’ on sticky notes like @BarackObama???”

But DACA is also a broadly popular policy, including with Republicans and Trump voters.

A long-term fix for the roughly 700,000 Dreamers comes back, once again, to Congress.

The Supreme Court, in another rebuke of Trump, rules that his decision to cancel DACA, a program that protected young immigrants, was not justified.

“DACA recipients must have a permanent legislative solution,” Sen. John Cornyn of Texas, a high-ranking Republican, said Thursday. “They deserve nothing less.”

Yet the Supreme Court may have given lawmakers even less motivation to act now than in the last eight years under the Obama and Trump administrations, said Steve Vladeck of the University of Texas School of Law: “Congress could fix this tomorrow — that’s the whole reason why we’re here.”

The president may be similarly grateful to the court for giving him political cover, Vladeck said.

“There’s a reason why they didn’t do it right the first time,” he added. “It’s not just incompetence — the administration relies on implausible arguments in order to try and deflect responsibility for ending DACA.”

Elora Mukherjee, director of Columbia Law School’s Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, predicted that the president wouldn’t move to change DACA, but would promise to — after November.

“The administration is figuring out what is the best way to use this opinion to capitalize on solidifying its base,” she said. “SCOTUS gives it cover to not move to change DACA immediately. ... ‘If you elect me, I’ll do this and much more in the next four years.’”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.