Can Trump campaign on a vow to end the disorder and unrest that he’s fueling?

- Share via

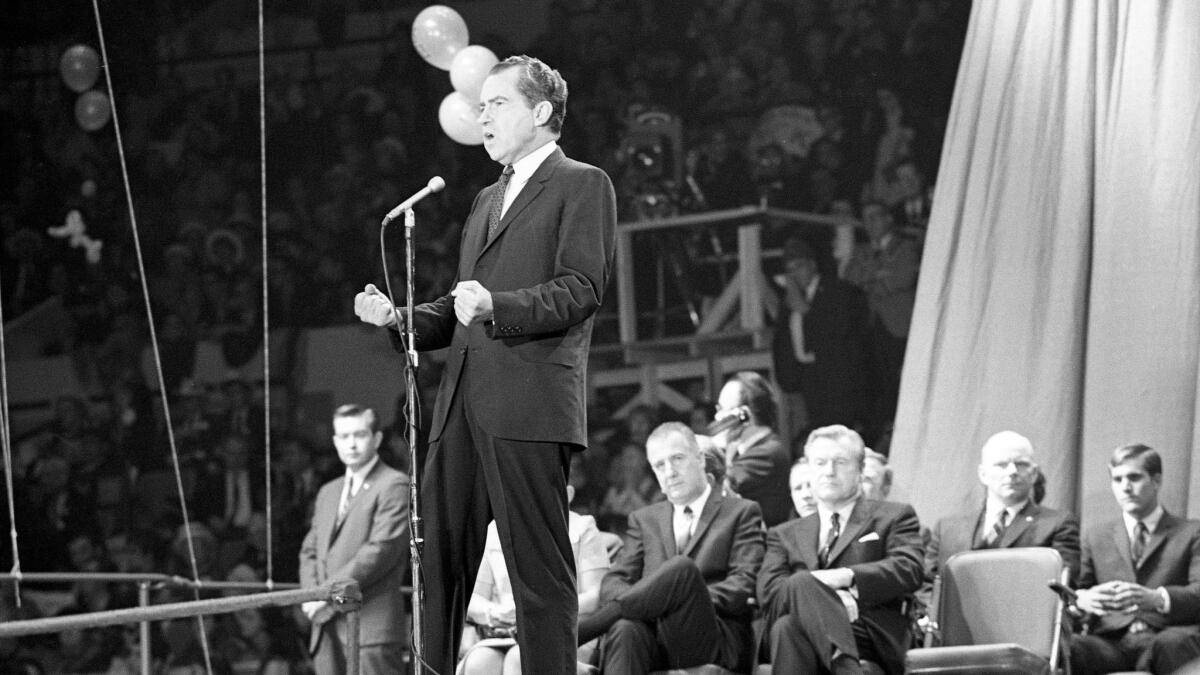

WASHINGTON — With protests erupting across the country, President Trump is ripping a page from Richard Nixon’s playbook, claiming to stand for “law and order” and calling out to the “silent majority” that he hopes will grant him a second term.

But 2020 is a long way from 1968, and there’s no assurance that Trump’s message will resonate the same way it did for Nixon decades ago.

For starters, while Nixon campaigned to end Democratic rule in Washington, Trump is no longer an outsider. He’s the incumbent president who promised to stop “American carnage” only to preside over the broadest outbreak of domestic unrest in generations.

In addition, with violent crime at historically low levels, American cities feel far safer now, potentially making a crackdown on lawlessness a less potent campaign topic.

“It’s not crime that’s the key issue,” said Neil Newhouse, a Republican pollster. “It’s really racial relations.”

The law does allow a president to send troops to a state over the state government’s objections, but only under specific circumstances.

Trump has only exacerbated those tensions as Americans protest the death of George Floyd, a black man killed when a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck while Floyd was handcuffed on the ground and begging for air.

And when the demonstrations eventually fade, the country will be still in the midst of record unemployment caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

“Looking ahead to what is going to be impactful in September and October, you’ve got to think it’s still going to be the economy,” Newhouse said. “I think that’s what voters are going to come back to.”

The overlapping crises have left Trump grappling for something to stop his slide in the polls, where he’s currently trailing Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee. Rather than heed renewed calls for police reform, he’s tried to project images of strength to his core base of white supporters.

“Weakness will never beat anarchists, looters or thugs, and Joe has been politically weak all of his life,” Trump tweeted Tuesday. “LAW & ORDER!”

On Monday, Trump threatened to deploy the U.S. military to quell riots if governors don’t “dominate the streets” with an “overwhelming law enforcement presence.” Police forcibly dispersed crowds of protesters outside the White House, allowing Trump to cross the street to visit a church that had been burned during demonstrations. After posing for photos, he walked between two lines of heavily armored officers and pumped his fist.

It’s a far different message from the one sent by Biden, who knelt in a symbol of protest after meeting with black parishioners in a church in Wilmington, Del. On Tuesday, the former vice president harshly criticized Trump’s handling of the protests and promised to support police reforms if elected in November.

Between the demonstrations, the coronavirus and the economy, the presidential race is going to hinge on the question of “who is going to be best to bring us back to normalcy,” said Jeff Roe, a Republican strategist.

He suggested that Trump’s renewed focus on security could help shore up support with key demographics, such as older voters and suburban women.

“If you match the two candidates up, he’s definitely going to make you more safe than Biden,” said Roe. “From a raw political standpoint, it’s absolutely an opportunity presented to the president.”

Some Democrats have expressed similar concerns.

“There are many decent white Americans who have reached the conclusion that they could not vote for Trump again, but now they may be scared,” said Ed Rendell, the former Pennsylvania governor who supports Biden. “Are they going to take a second look?”

However, the political landscape is far different from the one faced by Nixon, perhaps the best known example of a “law and order” presidential candidate.

A former vice president and U.S. senator from California, Nixon ran campaign advertisements in 1968 with scenes of violence and declaring “we shall have order in the United States.” Even though the videos showed white protesters, many viewed them as as a thinly veiled attempt to exploit racial animosities at the time.

John Farrell, who wrote a biography of the 37th president, said the message was also a reflection of a country wracked by division over the Vietnam War, reeling from a series of political assassinations and facing a years-long upswing in crime.

“The question in 1968 was not whether you were going to use law and order as an issue, but how you were going to present it,” Farrell said.

Nixon also had the benefit of campaigning against the Democratic establishment that had been in charge. President Lyndon Johnson had declined to run again, and his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, was seeking to replace him.

Trump has no such advantage as he runs for reelection.

“The fundamental difference is Trump’s in charge,” said Paul Maslin, a Democratic pollster. “He’s created this. He’s fanned the flames.”

They’re flames he’s been fanning for years. In 1989, Trump pushed for the death penalty for the Central Park Five, a group of black teenagers who were falsely accused of attacking a white jogger in Manhattan. He later promoted the baseless claim that President Obama, the first black president, was ineligible to serve in the White House because he wasn’t born in the United States.

He encouraged violence against protesters who disrupted his campaign rallies — “knock the crap out of them,” he said at one point — even as he promised “safety will be restored.”

“The crime and violence that today afflicts our nation will soon — and I mean very soon — come to an end,” Trump said in his speech as he accepted the Republican presidential nomination.

“It’s a decades-long Republican strategy,” said Matt Dallek, a political historian at George Washington University. “Trump is drawing on this tradition. But he’s also making it his own, because he’s the most divisive and inflammatory president we’ve had.”

Dallek added, “He’s more willing to say the racist and nativist pieces out loud.”

Since the protests over Floyd’s death began, Trump has repeatedly echoed the racist language and imagery of civil rights battles. He warned that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts” — a quote made famous by a Miami police chief in the 1960s — and said that the Secret Service was prepared to use “vicious dogs” against demonstrators outside the White House.

“We have turned a blind eye to his racial shortcomings for a very long time,” said Rep. Cedric Richmond, a Louisiana Democrat who is co-chair of Biden’s campaign. “Hopefully this will wake people up.”

Times staff writers Janet Hook and Mark Z. Barabak contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.