Bernie Sanders ends his presidential campaign

- Share via

Bernie Sanders on Wednesday suspended an anti-establishment presidential campaign that changed the course of Democratic politics and energized large groups of new voters but fell short of amassing a broad enough coalition to capture the nomination.

The Vermont senator’s decision came after his campaign stalled following a string of losses to former Vice President Joe Biden in large, delegate-rich states that left him with little chance of becoming the nominee. Yet Sanders came closer than any self-proclaimed socialist in U.S. history.

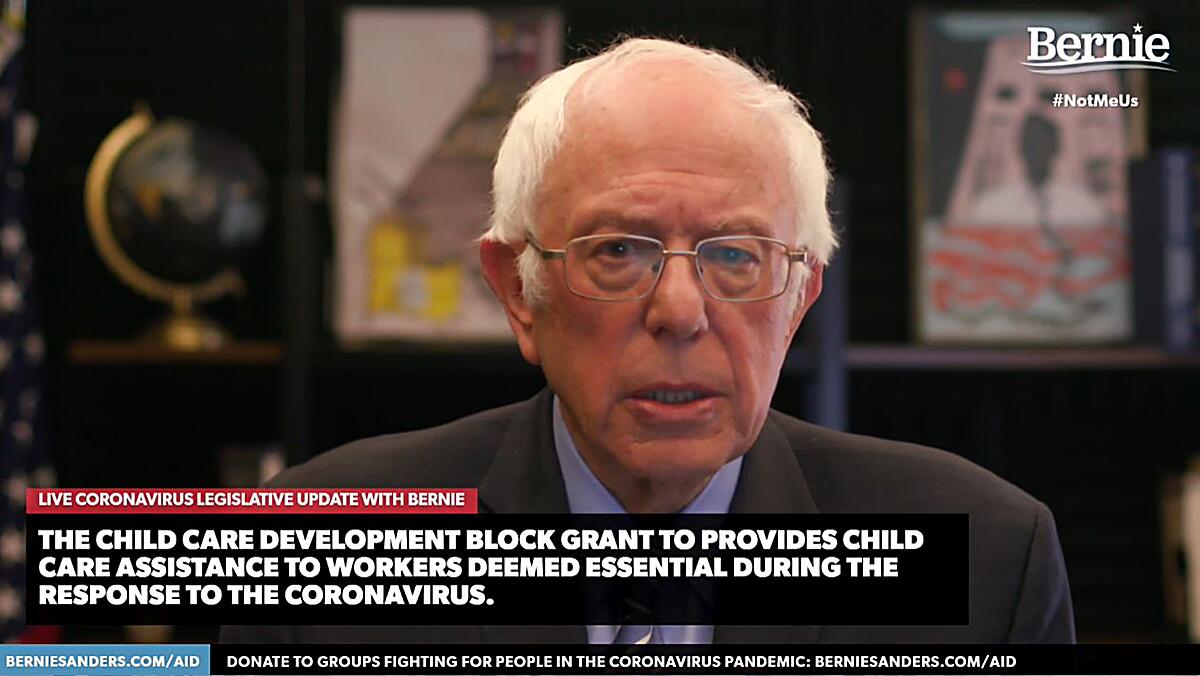

In an online address to supporters Wednesday morning, Sanders said the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated his decision to suspend campaigning.

“As I see the crisis gripping the nation, exacerbated by a president unwilling or unable to provide any kind of credible leadership, and the work that needs to be done to protect people in this most desperate hour, I cannot in good conscience continue to mount a campaign that cannot win and which would interfere with the important work required of all of us,” Sanders said.

The senator’s exit effectively makes Biden the nominee, but Sanders said he will remain on the ballot in all the states that have not yet voted. He will continue to gather delegates for the Democratic National Convention, where his supporters will use the influence to push the party platform in a more progressive direction.

“Few would deny that over the course of the past five years, our movement has won the ideological struggle,” Sanders said. “It was not long ago that people considered these ideas radical and fringe. Today they are mainstream.”

Biden moved quickly to reach out to Sanders supporters as he aims to unify a deeply fractured party.

“I know that I need to earn your votes,” Biden said in a statement. “And I know that might take time. But I want you to know that I see you, I hear you, and I understand the urgency of this moment. I hope you’ll join us. You’re more than welcome: You’re needed.”

It is not clear what concessions Biden has or is prepared to make to woo Sanders supporters. His top lieutenants have been in touch with Sanders in recent weeks. Biden and Sanders also talked directly, a conversation in which Biden explained why he was proceeding with his vetting of potential running mates even before Sanders had dropped out. Sanders offered words of support to Biden, but his followers have made clear Biden will need to work for their votes.

Sanders rebounded off his 2016 loss to Hillary Clinton to emerge for a few weeks as the front-runner in the current Democratic primary, before second thoughts about the wisdom of nominating him and voter anxiety over the COVID-19 pandemic moved Democrats to consolidate behind Biden. By the time Sanders dropped out of the race, Biden was already proceeding as the presumptive nominee.

Bernie Sanders announces that he has dropped out of the Democratic primary.

Even while falling short of the nomination, Sanders had a transformative impact on the Democratic Party. He upended old rules of money and politics, eclipsing his rivals in fundraising with a loyal army of nearly 2 million small donors whose contributions averaged $21.

Sanders successfully pushed the party to abandon the Clintonomics of the past in favor of a more progressive path, and he forced rivals to embrace a more expansive role for government.

Yet the Vermont senator struggled to expand his passionate base of supporters to the critical mass needed to win the race. He ultimately ran into the same electoral buzz saw in 2020 that he did in 2016, getting rejected by African American and suburban voters in many Sunbelt states whose support is essential to winning the nomination.

It was not for lack of effort. Sanders raised a passionate brigade of progressive volunteers, forged a near-unbreakable bond with younger voters and won over many Latinos, some of whom affectionately dubbed the 78-year-old Brooklyn native “Tío Bernie.” Sanders even survived a heart attack on the campaign trail in October only to see supporters double down on his candidacy.

Supporters cherish his consistency throughout his many decades in politics, during which Sanders never wavered from his democratic socialist agenda. But that stubbornness also cost the candidate with the mainstream voters he needed to win the nomination.

Sanders continued railing against the party “establishment,” sticking with his complimentary remarks about some of the policies of the Fidel Castro government in Cuba, even in the days leading up to the primary in Florida, with its large number of Cuban exiles and their families, and pillorying the news media until the final days of his campaign.

Although Sanders’ base was smaller than in 2016 — when some Democrats backed him solely as an alternative to Clinton — and he did not generate the record turnouts he said his political revolution would need, he thrived in what was initially a large and competitive 2020 Democratic primary field.

Burlington shaped Sanders as Sanders shaped Burlington, so much so that it’s hard to consider one without the other.

Progressives coalesced behind him while several moderates in the race splintered the rest of the vote. Sanders was aided by head-to-head polls showing him as one of the most popular candidates against President Trump in a general election.

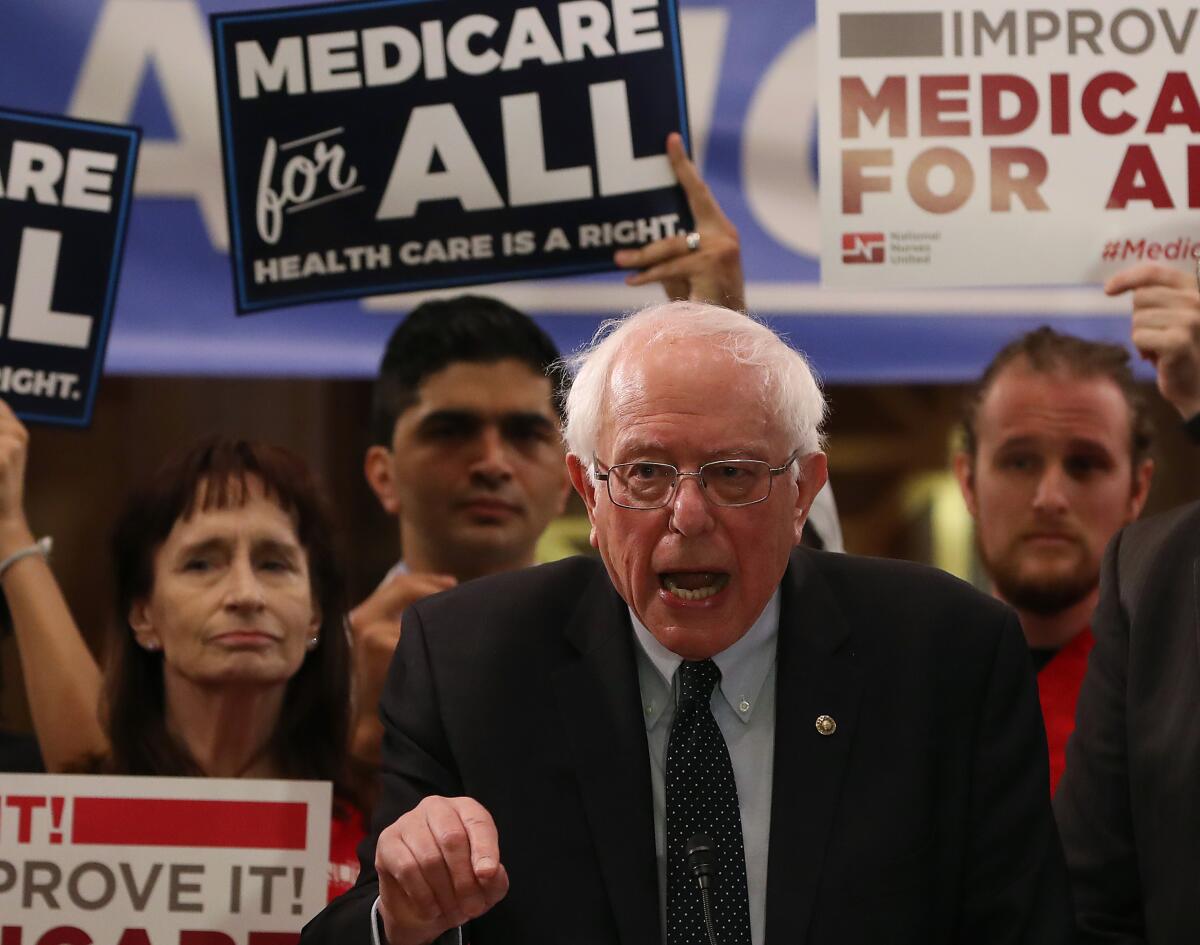

He made healthcare the race’s defining policy issue, polarizing the Democratic field with his crusade to nationalize the patchwork private health insurance system under a universal “Medicare for all” federal program.

Before moderates ultimately consolidated around Biden, Sanders’ unusual coalition drove him to strong finishes in the campaign’s first contests, in Iowa and New Hampshire, followed by a decisive victory in the Nevada caucuses.

At casino caucus sites along the Las Vegas Strip, Sanders’ Silver State victory was boosted by members of the state’s powerful Culinary Workers Union, many of whom ignored their leaders’ sharp criticism of Sanders’ healthcare proposal, which would eliminate the union’s high-quality private insurance.

It was the high-water mark of Sanders’ campaign. But within a week, the tide had turned. It became clear that Sanders, whose 2016 campaign was derailed by voters in the South, had not made the inroads needed to power through that part of the country in 2020, either.

At a debate in South Carolina, Sanders’ opponents and the moderators chiseled at his record of complimenting some social programs of far-left governments.

“We’re not going to win these critical, critical House and Senate races if people in those races have to explain why the nominee of the Democratic Party is telling people to look at the bright side of the Castro regime,” said Pete Buttigieg, former mayor of South Bend, Ind.

“Let us be clear: Do we think healthcare for all, Pete, is some kind of radical, communist idea?” Sanders shot back.

In South Carolina, black voters broke for Biden en masse after the state’s influential congressman, James E. Clyburn announced his support for the former vice president’s struggling campaign, one of the most consequential presidential endorsements in recent history.

After Biden’s runaway win, and with Super Tuesday just three days away, the once-large Democratic primary field quickly consolidated behind his candidacy. Buttigieg and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar dropped out of the race and immediately endorsed Biden, joined by former rival Beto O’Rourke of Texas.

In a single weekend, the presidential campaign had been flipped on its head. Black voters, the backbone of the Democratic Party, were firmly in Biden’s camp. Undecided voters and the former supporters of his opponents flocked to the well-known party leader.

Fifty-three percent of Latino voters in California plan to cast their ballot for Bernie Sanders, but not a single member of the powerful Latino Legislative Caucus has backed him.

The shortcomings of the Sanders bid came into stark relief on Super Tuesday, when his campaign had hoped to gain an insurmountable lead in the delegate race. Voters not inclined to support the Vermonter coalesced around Biden with unexpected force. Biden won 10 of 14 states, including some where he did not even campaign.

Young voters, Sanders’ core base, did not turn out in unusually large numbers. Instead, it was Biden supporters in the suburbs who pushed turnout to record levels in some states. And pro-Sanders Latinos were concentrated in too few states out West, such as California and Colorado, to offset Biden’s strengths elsewhere.

As Democratic leaders announced their endorsement of the surging Biden, Sanders looked increasingly isolated.

Even when his fellow progressive Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts dropped out, it was uncertain whether a majority of her supporters would shift to Sanders’ camp. Prominent liberals who were otherwise sympathetic to Sanders’ policy goals publicly complained about online harassment they’d received from his most aggressive followers.

Over the ensuing two weeks, Biden swept through a series of major states — Michigan, Illinois, Florida, Arizona, even Washington, where Sanders had triumphed in 2016. As the spreading coronavirus eclipsed the campaign, shutting down rallies and leading Ohio officials to postpone that state’s primary, Sanders struggled to retain voters’ attention.

He was trailing well behind Biden when Democrats went to the polls Tuesday in Wisconsin, another state where Sanders won big in 2016.

But Sanders had a big impact on the party ideologically, with the left-wing contours of his 2016 campaign showing up in the platforms of his 2020 opponents.

Warren had almost wholeheartedly embraced Sanders’ proposal for Medicare for all, and even moderates promoted public options that would go far beyond the advances of the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act.

The Democratic field promoted sweeping pro-union platforms that were more in line with European social democracies than recent trends in American labor policy. Biden adopted a version of Sanders’ free-college-for-all proposal, limiting it to families with incomes below $125,000. Sanders’ 2016 plank to lift the minimum wage to $15 was no longer envelope-pushing; it was the norm.

But with the party’s likely nomination of Biden, its most prominent middle-of-the-road option, Sanders supporters’ hopes of a “revolution” have once again hit the rocks.

Pearce reported from Los Angeles and Halper from Washington. Times staff writer Janet Hook in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.