As Alabama shows, Bloomberg’s ad spending buys him favor in often-overlooked states

- Share via

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — For years, Democrats running for president have given little thought to crimson-red Alabama, even in party-nominating contests.

With only 52 pledged delegates to the Democratic convention — a fraction of California’s 415 — this Deep South state is far from the biggest prize on Super Tuesday, March 3, when 14 states with about 40% of the total delegates are up for grabs.

But Michael R. Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York, has been giving attention — and money — to Alabama. And the state’s receptivity illustrates a major reason why his big-spending bid for the nomination forges ahead despite his widely derided performance in last week’s debate, which caused a significant drop in his national standing in some polls.

His investment has bought Bloomberg some favor here and in other under-the-radar Southern states, including Arkansas, Tennessee and Mississippi, where local Democrats are unaccustomed to the attention.

The media-company billionaire is focusing on Super Tuesday states, vastly outspending Democratic rivals without his riches who’ve been concentrating on the early-voting states that Bloomberg is sitting out.

As of Monday, Bloomberg had spent more than $191 million on advertising in Super Tuesday states, according to Advertising Analytics. That compares with $36 million for the next-highest spender, billionaire Tom Steyer, $12 million for Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and minimal amounts for other Democrats.

In Alabama, he has poured more than $8 million into TV and radio ads in the last two months while Sanders has spent just $142,000 and two of his main competitors, former Vice President Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind. — have not advertised. Bloomberg has visited Montgomery twice, opened up four campaign offices and hired 30 people while most of his rivals have two paid staffers or fewer.

Part of Bloomberg’s pitch is that national Democrats have long neglected the South, essentially ceding states like Alabama to Republicans, and he’ll change that.

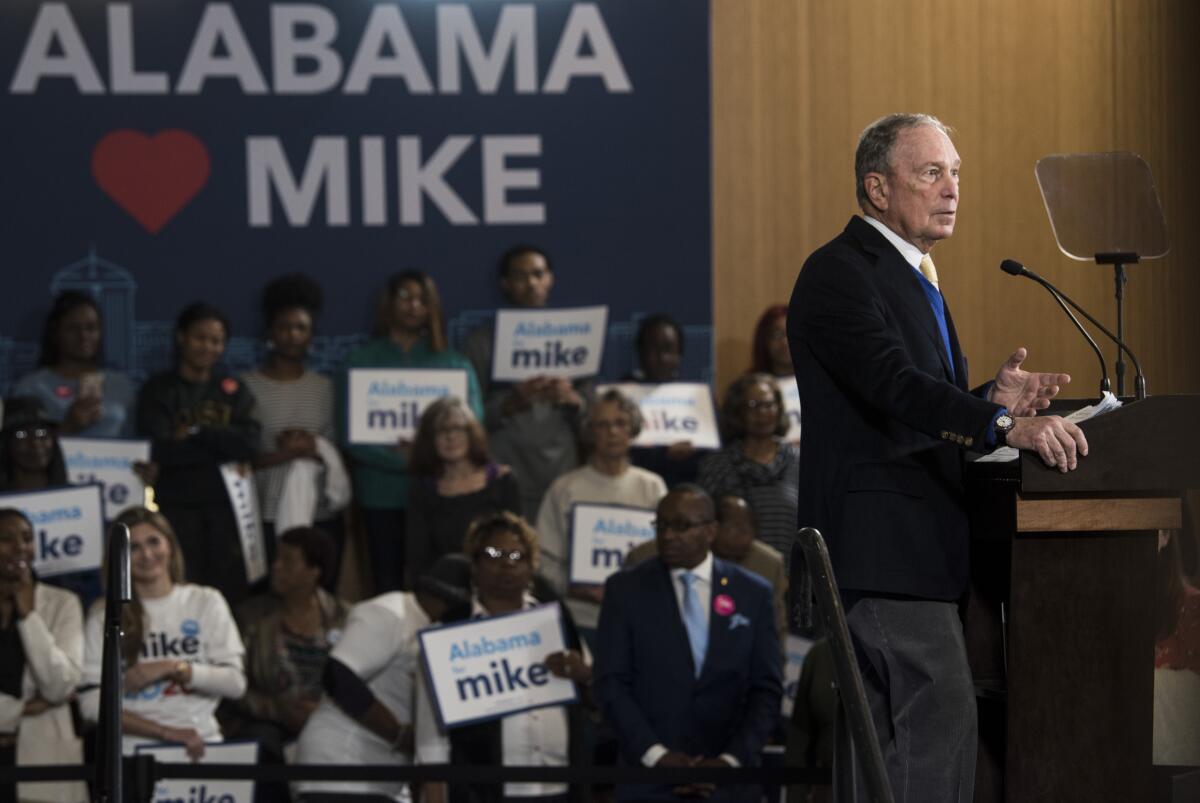

“I believe it’s time for the national Democratic Party to stop ignoring Alabama,” he said earlier this month to the Alabama Democratic Conference.

“I’ve devoted a lot of my resources to those swing states from Michigan and Wisconsin to Florida and Arizona, but I’m also working to create what we call a new generation of swing states — states like Alabama and Texas, which could very well turn blue if more people voted.”

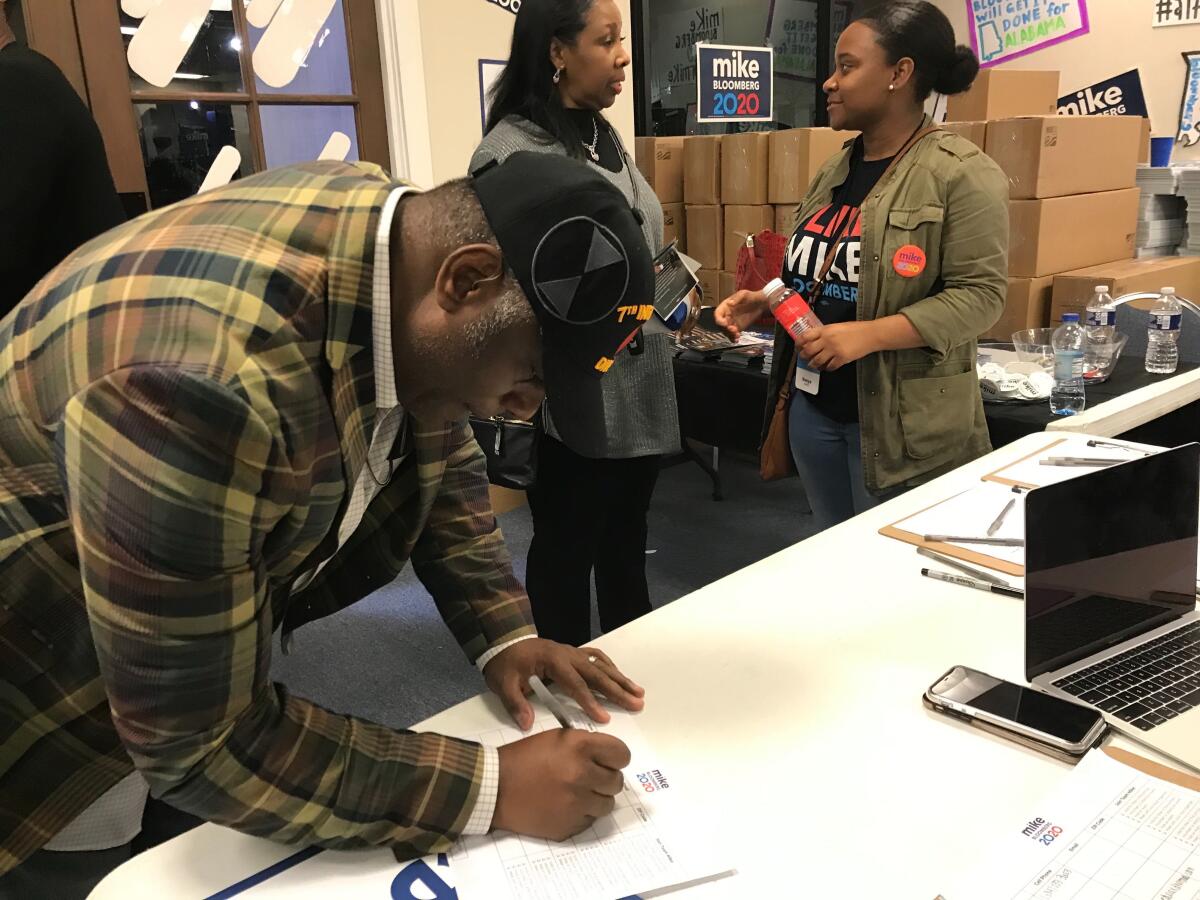

One evening last week, dozens of people — retired teachers and professors, small business owners and veterans — showed up for the opening of Bloomberg’s office in downtown Montgomery, opposite a statue of civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks and near the state Capitol. Passing a table loaded with “Mike for President 2020” buttons and yard signs, many signed up to volunteer.

“Biden’s not really doing good,” said Grace Stewart, 68, a retired supervisor for General Motors. She said she liked Bloomberg’s messages on TV about gun violence and climate change, as well as his investment in Democratic causes.

“This is the first time I ever volunteered,” she said softly, clutching a Bloomberg T-shirt. “I’m not really a volunteering type of person, but we’ve got to get Trump out of office. I think Bloomberg’s a candidate that can win against Trump.”

Some of the other candidates are organizing here. Sanders has more than 1,000 volunteers contacting voters through phone banks and knocking on doors across the state. The Buttigieg campaign plans 100 events Saturday. Still, Bloomberg has likely amassed the largest Democratic presidential staff in Alabama history, Democrats say.

“His presence is overwhelming,” said Montgomery Mayor Steven Reed, who was elected last fall as the first African American in the office.

“It matters,” Reed added. “It helps him gain some traction in communities that may not have been touched by a campaign.”

Reed has yet to endorse any candidate. But his father has. Joe Reed, the leader of the Alabama Democratic Conference, the party’s primary black caucus, surprised many in this majority-black Southern city a few weeks ago when he endorsed Bloomberg.

His group, which works to get blacks to vote, plans to put Bloomberg’s name on more than a half-million sample ballots and distribute them in every county.

“We’ll take them door to door, from church to church, from barbershop to barbershop,” Reed said. “We’re going to try our level best to help him.”

As in other Southern states, Biden has long been favored among black voters who make up the majority of Alabama Democrats, given his strong association with former President Obama and past visits to Birmingham, Selma and Montgomery.

“The fact is the people in Alabama really don’t know Bloomberg — unlike Joe Biden, who has been into Alabama for a long time,” said Sen. Doug Jones, a Biden supporter. In 2017, Biden came to Birmingham to campaign for Jones.

But while Biden has won the endorsement of Jones and some other party leaders, including Rep. Terri A. Sewell and Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin, his poor showings in Iowa and New Hampshire, and his distant second-place finish behind Sanders in Nevada on Saturday, did not help his case with undecided officials.

With no clear front-runner nationally, and little competition here yet, Bloomberg has seized the opening to spread the message that he is experienced, well-funded and the candidate who can beat President Trump.

“His strategy of skipping the first four states is incredibly risky,” said Andra Gillespie, associate professor of political science at Emory University. “But with Joe Biden’s campaign having faltered, and perhaps having stumbled irrevocably, his strategy doesn’t seem to be as far-fetched or quixotic as it once did.”

A former Republican, Bloomberg faces challenges in courting black voters after strong criticism of his support as New York mayor of stop-and-frisk policing and his suggestion that the end of redlining contributed to the 2008 economic collapse. Yet locals say his wealth allows him to get noticed, especially among older, more moderate black Democrats uncertain whom to support.

“Bloomberg has had a free hand in places like Alabama to be nothing but positive,” said Glen Browder, a professor at Jacksonville State University and a former Democratic congressman. “When Bloomberg comes to town flush with cash, not asking for contributions and just saying, ‘I’d like to have your support,’ that’s a pretty powerful introduction.

Bloomberg’s money is central to such calculations, as voters made clear.

“He’s the first person who can afford to spend money on his campaign with no reservation,” said David Sadler, 46, the owner of a concierge company and former mayoral candidate, adding, “I don’t think you should punish someone who has resources.”

Addressing those who turned out for Bloomberg’s office opening here, Joe Reed won loud applause when he said that he considered Biden a good friend, but he wanted to beat Trump.

“I’ve been around a good little while and this is one campaign we don’t have to shoot marbles to raise money,” he said. “We don’t have to roll the dice or anything. We can win big!”

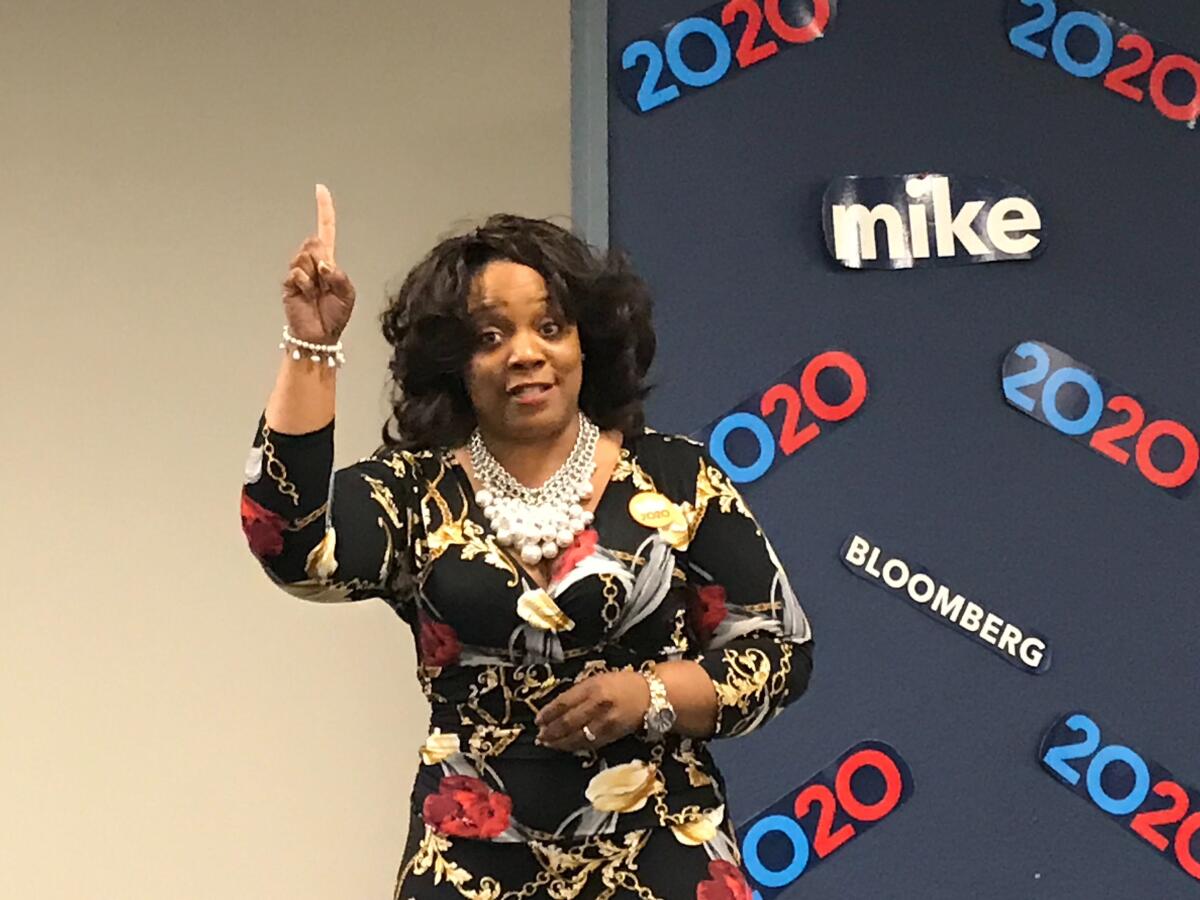

Merika Coleman, assistant minority leader of the Alabama House, dismissed the talk about stop-and-frisk, noting favorably that Bloomberg supports Everytown for Gun Safety, the national nonprofit group that advocates for gun control.

“He put money behind making sure that our children are safe,” she said. “Mike Bloomberg has put his money where his mouth is.”

Whether they support Bloomberg or not, many Alabama Democrats are grateful for his investment in a state where no Democrat has held statewide office since 2012.

“The infrastructure and the level of organization structure the Bloomberg campaign has in place has to get your attention,” said Anthony Daniels, minority leader in the Alabama House, who has not yet endorsed a candidate. “Win or lose, he’s going to be engaged in the long haul. For me, that speaks volumes.”

Whoever wins the Democratic nomination, no one here is unrealistic about the nominee’s chances in November in Alabama, which favored Trump over Hillary Clinton by 28 percentage points. Yet local Democrats say that Bloomberg’s investment — he has vowed to keep his offices operating even if he’s not the nominee — could buoy endangered down-ballot Democrats, such as Jones, and help them capture two congressional seats.

“All of this energy happens in battleground states every cycle, but we don’t really see it here,” said Leanne Townsend, Bloomberg’s Alabama regional organizer, who spoke giddily of how he is spending to train volunteers on voter contacts, data management and canvassing.

Not everyone is so enamored of Bloomberg’s money.

“It was stated that money can’t buy elections, but it certainly buys you a VIP table,” said Sean Champagne, a 27-year-old attorney and a democratic socialist who favors Sanders. Casting a withering look at the Bloomberg campaign office as he strode by, Champagne said he was troubled that Bloomberg could enter the race so late and gain momentum by opening his wallet.

“He is emblematic of everything that’s wrong with U.S. politics,” Champagne said.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.