Andrew Yang drops out of presidential race

Democrat Andrew Yang, who promised to give every American adult $1,000 per month, ends his presidential bid.

- Share via

Entrepreneur Andrew Yang, whose quixotic presidential campaign revolved around giving every adult U.S. citizen $1,000 per month, ended his bid for the White House on Tuesday after failing to garner significant support in the New Hampshire primary.

“We have touched and improved millions of lives and moved this country we love so much in the right direction. And while there is great work left to be done, you know I am the math guy. And it is clear tonight from the numbers that we are not going to win this race,” Yang told supporters in Manchester, N.H., shortly after the polls closed. “I am not someone who wants to accept donations and support in a race that we will not win.”

The ability of the 45-year-old who has never held elected office to make it this far — outlasting far better-known politicians — was one of the surprises of the 2020 presidential campaign. He was the last candidate of color to make the Democratic debate stage.

The lawyer turned businessman decided in late 2017 to run for president because he believes the government is not taking seriously how automation is going to disrupt the economy and eliminate millions of jobs. He proposed a form of universal basic income — the monthly stipend — to partly compensate for the job losses.

His views on automation, shared in February 2019 on Joe Rogan’s podcast, YouTube and social media, started to attract a following and more exposure on television and the internet. His presentation — part data-driven descriptions of a dystopian future, part dry Gen-X-style witticisms, part optimistic earnestness — struck a chord among disaffected voters as well as former supporters of President Trump and Sen. Bernie Sanders.

As he ended his campaign, Yang vowed to support the eventual Democratic nominee, but he cautioned the remaining candidates to not forget the economic disruption that he believes caused Trump’s election in 2016.

“Donald Trump is not the cause of all of our problems. He is a symptom of a disease that has been building up in our communities for years,” Yang said. “We must cure the disease that got him elected. And in order to do that we must address the real problems that affect our people and offer solutions to actually solve them.”

Yang pledged to continue fighting for those losing their livelihoods because of economic upheaval.

“While we did not win this election, we are just getting started,” he said, as supporters started chanting “2024! 2024!” “This is the beginning. This movement is the future of American politics. This movement is the future of the Democratic Party.”

Yang was clearly not a politician, and his supporters relished that. He signed bongs. He refused to wear a tie to debates. (Democratic rival and fellow Phillips Exeter Academy alum Tom Steyer gave him one for Christmas.) And Yang frequently joked about his Taiwanese heritage, saying that he was the opposite of Trump: “An Asian man who likes math.” The line drew laughs from supporters but cringes from some Asian Americans.

2020 presidential contender Andrew Yang wows his “YangGang” in L.A.

The candidate may be known for his antics, which have recently included throwing axes and crowd-surfing. But his empathy also touched a chord with voters. During a recent event in Ames, Iowa, he paused his speech and wandered into the crowd to hug a young man whose parents struggled with opioid addiction.

This combination of human connection and sardonic wit gained a fiercely loyal online following known as the “Yang Gang,” reminiscent of the “Bernie Bros” and the “Ron Paul Revolution.”

Supporters have tattooed a Yang campaign slogan, MATH — “Make American Think Harder” — and his face onto their bodies. They complained loudly when they believe the media or the Democratic National Committee short-changed their preferred candidate. He also received an eclectic mix of endorsements, from Tesla founder Elon Musk to comedian Dave Chappelle.

2020 presidential candidate Andrew Yang is little known but loved by his “Yang Gang.” He has qualified for the Democratic debates while some lawmakers did not.

Yang spoke seriously about how economic disenfranchisement is leading to higher suicide and drug overdose rates, and how society needs to rethink how it judges an individual’s worth. He pointed to his wife, Evelyn, who raises their two children, including one who has autism. That work may not contribute to the GDP, Yang said, but it has value.

Yang’s wife was thrust into the spotlight in January when she told CNN that she was sexually assaulted by her physician while she was pregnant with her first child. She said during a women’s march that month that she hoped telling her story would help other victims find their voices.

Yang called his wife “the bravest woman I know,” in a statement. “I hope that Evelyn’s story gives strength to those who have suffered and sends a clear message that our institutions must do more to protect and respond to women.”

In the early stages of his campaign, Yang was viewed by most political observers and his rivals for the Democratic nomination as a curiosity. But then he began to qualify for debates that senators and governors failed to make.

January’s debate in Des Moines was the first time he didn’t make the stage. But his supporters made sure he was not forgotten: On the day of the debate, #AmericaNeedsYang was the second-most trending topic on Twitter in the United States.

That night was perhaps a demonstration of the dynamics of his entire campaign — wildly successful online, but less so among the tradition-bound caucus-goers and primary voters who pick the Democratic nominee.

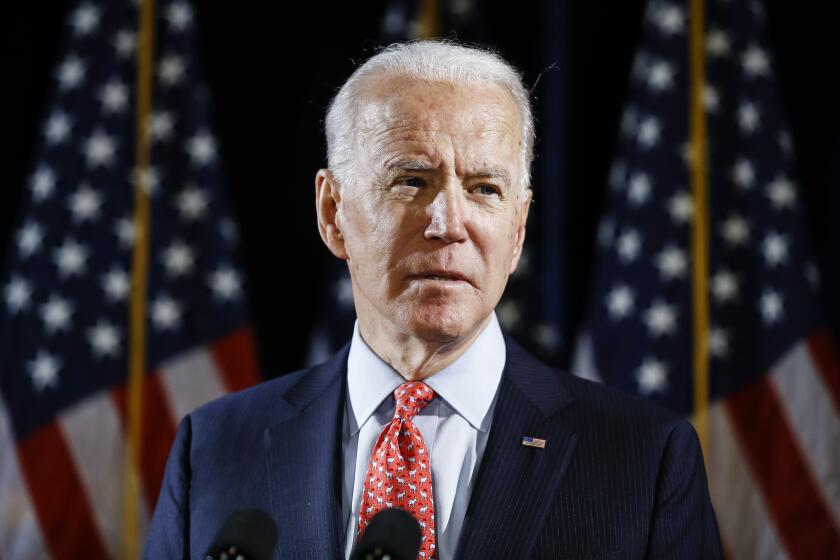

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.