Warren’s once high-flying campaign has lost altitude. She has a plan for rising again

- Share via

MANCHESTER, N.H. — Last winter, Sen. Elizabeth Warren wowed Tom Courtney by cold-calling the former Iowa state senator and talking for a half-hour. After a campaign event in his hometown of Burlington, she sweet-talked his 8-year-old great-granddaughter. Warren impressed him as she built an imposing political organization across Iowa.

Now he’s not so sure about her. The Massachusetts senator has suffered from weeks of attacks by rivals, and Courtney is coming back to an issue Warren has struggled to put to rest: electability.

“I don’t know if she can beat Trump,” said Courtney, who is the Des Moines County Democratic co-chair and has not endorsed any candidate.

Having seen her high-flying political balloon lose air in recent months, Warren is now trying to regain altitude with voters like Courtney, by stepping up her criticism of Democratic rivals and sharpening the economic message that lifted her into the top tier of 2020 presidential candidates last summer.

With a speech in New Hampshire on Thursday and a three-day campaign swing through southeastern Iowa beginning Saturday, Warren is trying to hone her closing argument to voters, connecting her populist economic agenda and her crusade against corruption.

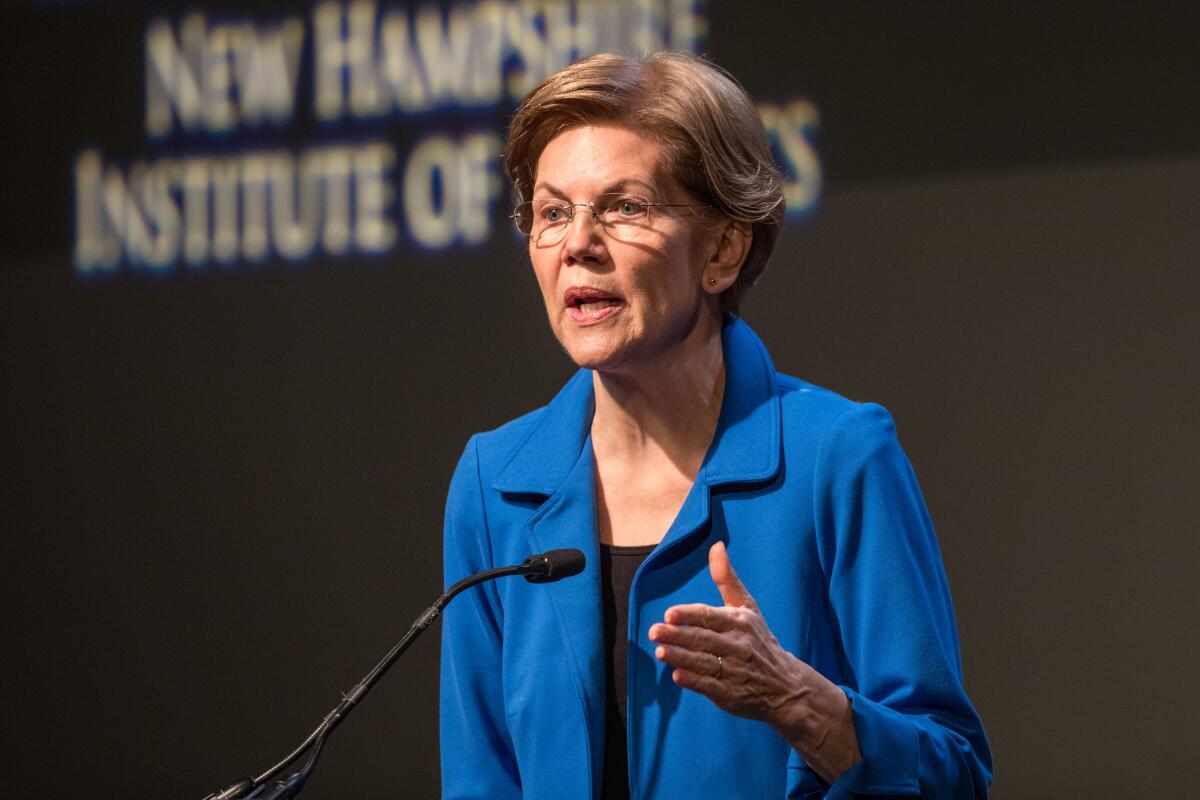

“Our problem isn’t big government,” she said in an hourlong, teleprompter-guided speech at the New Hampshire Institute of Politics at St. Anselm College. “It’s a government that’s been captured by the rich and the powerful.”

In a notable shift away from her mostly positive campaign of the last year, the speech was riddled with not-so-veiled criticism of her centrist Democratic rivals, especially former Vice President Joe Biden and South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg. She cast both as falling short in their commitment to change. Mostly spared from barbs was her progressive rival, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

“No other candidate has put out anything close to my sweeping plan to root out Washington corruption,” she said. She chided Biden -- although not by name -- for once telling a group of donors that “nothing would fundamentally change” if he becomes president, a comment he made at a fundraiser in explaining that tax increases he was proposing for the rich would not affect their standard of living. She also derided him for having the “naive hope” that Republicans would be easier to work with after President Trump leaves office.

Warren, who has sparred with Buttigieg over campaign finance transparency, in her speech suggested that he “brags” about his big-donor network and “offers them regular phone calls and special access.”

Buttigieg’s campaign responded with a statement that 98% of its donations were under $200. Spokeswoman Lis Smith punched back, saying, “Sen. Warren’s idea of how to defeat Donald Trump is to tell people who don’t support her that they are unwelcome in the fight and that those who disagree with her belong in the other party.”

Biden responded at a fundraiser in Palo Alto: “I read a speech by one of my — good person — one of my opponents, saying that, ‘You know, Biden says we’re going to have to work with Republicans to get stuff passed.’ I thought, ‘Well, OK, how are you going to do it? By executive order?’ ”

Going negative carries some risk for Warren, who has prided herself on taking the high road. Yet some of her supporters in the New Hampshire audience were glad to see more of a fighting spirit -- especially because she is a female candidate -- and said it might allay some of the concerns about her ability to take on Trump.

“She needs to do that,” said Deb Johnson, a retired federal employee from Brookline, N.H. “She’s falling in the polls and has got to do something to lift her back up.”

Despite Warren’s lost ground after steadily rising in polls through the year, allies see such shifts as inevitable in a race with no commanding front-runner, producing a fluid competition among the top vote-getters -- Biden, Sanders, Buttigieg and Warren -- that will keep them trading places.

She began drawing fire this fall as she came to be seen as the front-runner. As Buttigieg has risen into the top tier, he has joined her on the firing line. Last week he bowed to criticism from her and others and announced he would open his fundraisers to the press, and he also disclosed the names of the clients he worked for during his years as a corporate consultant.

The increasingly combative tone among candidates is a sign that the long primary campaign is entering a new phase: With voting to begin in less than two months in Iowa and New Hampshire, candidates are under increasing pressure to hone their message and distinguish themselves from their rivals.

“It’s starting to get time to pick your candidate,” said Esther Dickinson, a Concord, N.H., lawyer who recently endorsed Warren. “Contrast can help with that.”

The time for hands-on campaigning in Iowa could be cut short for Warren and other members of the Senate running for president, because much of January could be consumed by the Trump impeachment trial. Face time with Iowa voters is especially important to Warren, her supporters say, because her skill at making personal connections has been a big factor in her rise.

“If they see her and hear her, that’s going to make a difference,” said Twyla Peacock, Democratic Party chair and a Warren backer in Van Buren County.

For months, Warren’s economic message has been shadowed by rivals’ attacks on her healthcare policy and questions about her electability, raising doubts about her among Democratic primary voters on the two issues most important to many of them.

Those attacks have taken a significant toll in Iowa, where Buttigieg has risen to the top of most polls at her expense. The two are ideologically very different, with Warren appealing to progressives and he to more centrist voters. But they are competing for a demographic group that holds great sway in Iowa: college-educated whites.

The rivalry between Warren and Buttigieg has been simmering since the Democrats’ debate in October, when he directly attacked her for, among other things, not saying how she would pay for her “Medicare for all” plan.

When Warren put out a detailed plan designed to show that her proposal could be financed without raising taxes on the middle class, it was criticized from the right for being too expensive and unrealistic. Thrown on the defensive, she released a follow-up plan that called for phasing in Medicare for all more gradually, which drew criticism from the left.

It was a politically damaging episode that was off-brand for a candidate who made her name as a surefooted, detail-oriented policy wonk. The attacks spooked many voters about Medicare for all by playing to their fears that it would leave them with worse health coverage than they have now, said Peter Leo, a Warren supporter who is Carroll County Democratic chairman in Iowa.

“They used scaremongering tactics like what the insurance industry would use. It depressed people,” Leo said. “The smart thing for her to do now -- and she is doing it -- is to focus on her core message.”

That is the goal of her tour of southeastern Iowa, billed as the “Fair Share Road Show.” Warren plans to underscore how her policies would help individuals and also benefit the broader economy. To amplify her message on corruption, Warren has recently launched two new ads on the issue in Iowa.

“I’m not afraid to stand up to billionaires and corrupt politicians,” says one ad that reviews her career as a consumer advocate. “I’ve been doing it for years.”

Warren also has taken to tweaking her town hall format -- to give a shorter stump speech. That allows more time for questions and answers, which her advisors hope will also show her warmer, accessible side.

The new format recently produced an emotional exchange that went viral, when a tearful Warren told a young Iowa woman about how hard it was to tell her mother she was divorcing her first husband. Warren tweeted a video clip of the exchange.

Courtney, whose hometown is hosting one of Warren’s stops Monday, said she is smart to change things up because many Iowa voters have seen her before and are overwhelmed with attention from candidates flooding into the state for the final weeks of campaigning.

“We’re oversaturated here,” Courtney said. “‘I got a plan for that’ was neat at first. But it’s getting a little old.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.