Kamala Harris leaves a void in California and rivals rush in

Sen. Kamala Harris cited money troubles as she abandoned her campaign for president.

- Share via

Before California Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon even knew that Kamala Harris, his preferred candidate, had backed out of the presidential race, his phone was buzzing with a surrogate from one of her rivals to gauge his interest in endorsing. By day’s end, he’d heard from three other campaigns.

“Tom Steyer tried to reach out,” Rendon, a Democrat from Lakewood, said of the billionaire activist, “but apparently he had the wrong number.” (They eventually connected Wednesday.)

The instantaneous scramble for Democratic presidential candidates to bolster their California support after Harris’ sudden departure on Tuesday added to the uncertainty in the lead-up to the state’s March 3 primary. Four different candidates have led in Golden State polls over the course of the campaign, and two billionaires, Steyer and recent entrant Michael R. Bloomberg, have the capacity to shake the standings up further by blanketing the state with TV ads.

Harris, the first-term California senator, had hardly locked down her home base. Her decline to single-digit support in California polls mirrored her slump nationally.

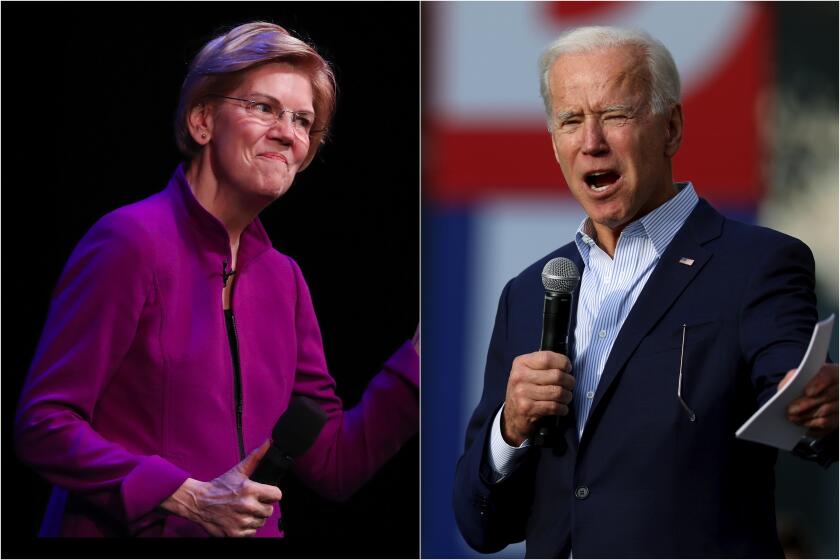

A Los Angeles Times/Berkeley IGS survey conducted just before her withdrawal found most Harris backers would jump to former Vice President Joe Biden or Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Ind., would pull in modest support.

“California voters pay more attention to national politics than they do to state or local,” said Anthony Reyes, a Los Angeles-based communications strategist. “National figures like Biden, Warren and Bernie obviously have strong support, so they stand to benefit the most.”

There is no home-state advantage in a place too big and costly for political loyalty. Winning California requires winning elsewhere first.

History suggests that Californians’ candidate preferences will shift dramatically in February as results roll in from the first four states to hold Democratic nominating contests. Winners of the early races typically benefit from a burst of national media coverage that makes them look like viable contenders, while the losers struggle to be seen as having a real shot at victory.

Most voters prefer candidates they see as having a reasonable chance of winning, said Democratic pollster Mark Mellman.

“What happens in Iowa, New Hampshire, and even in Nevada and South Carolina, will have much more impact on what happens in California than anything that’s happened so far,” said Mellman, who has worked on California campaigns. “The momentum that comes out of the earlier races has a profound impact.”

Even though she lagged with the state’s voters, Harris’ biggest advantage in California was her strong ties to its political establishment, from high-profile elected officials to moneyed donors to influential liberal interest groups.

Rick Zbur, executive director of Equality California, an LGBTQ rights group, said that many in his community were torn between Harris, whose working relationship with the group dates back years, and Buttigieg, whose candidacy as an openly gay man holds particular resonance.

“With Sen. Harris leaving the race, you’ll see a lot of those donors coalescing around Mayor Pete,” Zbur said.

Among the major political figures now up for grabs is Gov. Gavin Newsom, who endorsed Harris in February. His plans to stump for her later this month were canceled after her abrupt exit.

“I was going to Iowa in a couple of days. I just bought my damn ticket,” Newsom joked at a news conference Wednesday. “I want a reimbursement.”

Newsom is unlikely to back a new candidate immediately, according to a source close to the governor.

On Wednesday, the Biden campaign touted its first success at flipping an ex-Harris endorser: Los Angeles-area Assemblyman Mike Gipson. The former vice president already has the support of California’s senior U.S. senator, Dianne Feinstein, and nearly two dozen other elected Democrats in the state.

Biden, who has had trouble raising money, has had a slow start in California. His campaign says it has seven staffers here, but it has not yet opened any offices.

Buttigieg, who frequently visits on fundraising jags, has five full-time paid staffers on the ground. Warren has already opened two offices — a Los Angeles headquarters and a satellite in Oakland — and has held four town halls in the state, in addition to attending a number of forums.

The most aggressive field operation in California is Sanders’. His campaign has five offices with 80 paid staffers. Tens of thousands of Californians have attended his 19 events so far.

Two politically powerful unions — United Teachers Los Angeles and National Nurses United — and more than 80 elected officials in the state are backing Sanders, who is also devoting outsized resources to building support among California Latinos.

“Bernie is ahead of the game — there’s no question about that,” said Bill Carrick, a veteran Los Angeles Democratic consultant.

Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg rise in a poll of California Democratic primary voters. Mike Bloomberg is the most unpopular candidate in the field.

The byzantine system used by California Democrats to allocate the party’s 495 delegates — the biggest trove in the country — makes endorsements more important in the presidential primary than they are in most elections.

Just over half of the state’s delegates are allocated by congressional district; there are 53 in California. A candidate must receive at least 15% of the vote in a congressional district to win its delegates.

As a result, elected officials’ local volunteer operations can be crucial to reaching the threshold for winning delegates in every corner of California.

While most of the top-tier campaigns have focused on building up relationships and a presence on the ground, the two billionaires in the race have already taken to the airwaves, a more effective way to build support in this state of nearly 40 million residents spread across 164,000 square miles.

It’s a tactic that would be cost-prohibitive for most campaigns, which will need to buy ads in early-contest states as well as in the Super Tuesday states coast to coast.

It costs at least $1 million a week to air enough ads to have any impact, said Sheri Sadler, one of California’s top ad buyers.

“TV is still king in the political world,” she said.

That gives an advantage to the self-funding contenders vying for the Democratic nomination: Steyer, who used to run a San Francisco hedge fund, and Michael R. Bloomberg, former mayor of New York. Both have started TV advertising in California more than three months before the primary.

Bloomberg has already spent roughly $6 million on his first two weeks of advertising in California, Sadler estimates. “That is huge,” she said.

“I’m not going to be shocked at all if Bloomberg starts moving up, at least in California,” said Michael Trujillo, a Los Angeles-based Democratic strategist. “If you’re on TV every single day, it’s going to have an impact in our state.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.