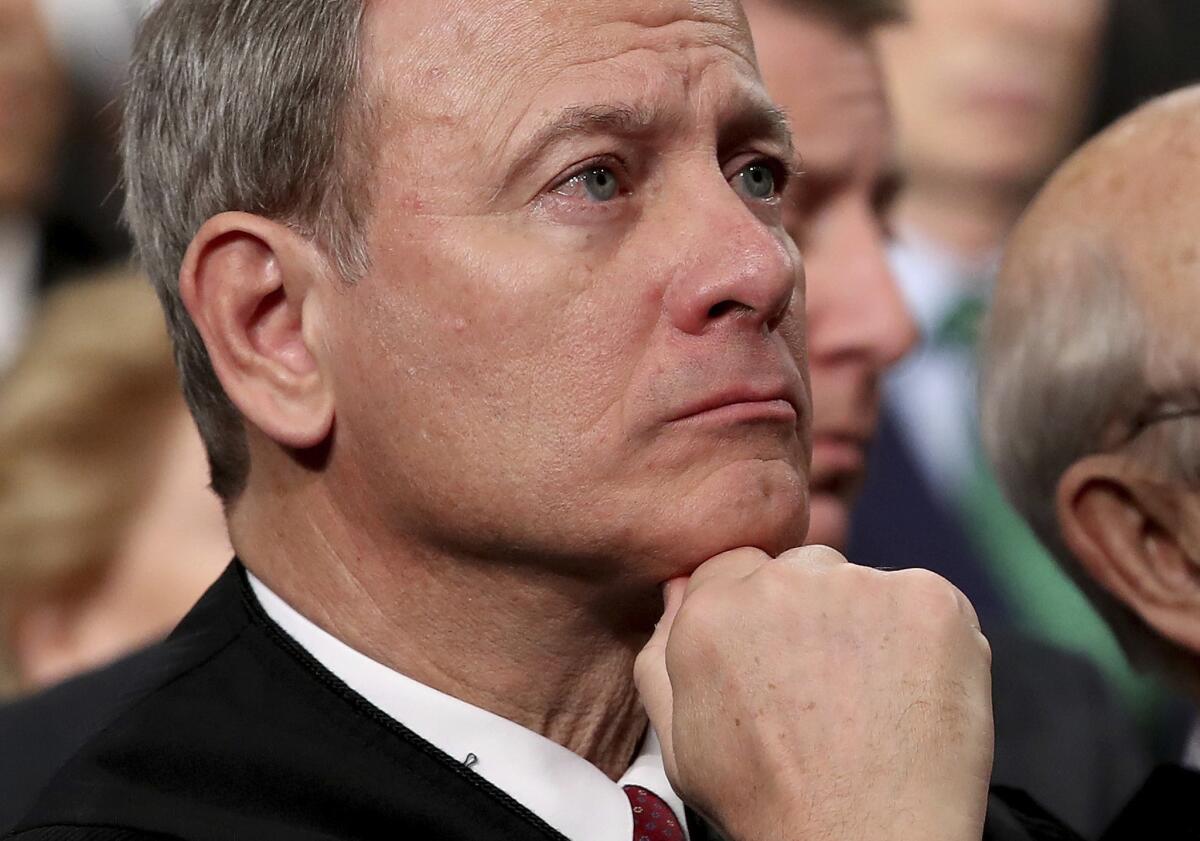

Supreme Court case of Trump vs. ‘Dreamers’ may come down to Chief Justice Roberts

- Share via

WASHINGTON — A somewhat reluctant Supreme Court will hear arguments Tuesday in this year’s most far-reaching immigration case and decide whether President Trump was justified in seeking to revoke a popular Obama-era policy that allowed more than 700,000 immigrants brought to the country illegally as children to temporarily live and work in this country.

Given the conservative majority on the court, the so-called Dreamers’ best hope for victory almost surely depends on Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.

Though Roberts has repeatedly ruled that the president enjoys broad powers when it comes to immigration, he is also one of the few remaining conservative justices who has shown a willingness to side with liberals on high-profile cases, including one recently in which he agreed that the Trump administration had not adequately defended its actions — the same issue in play in the Dreamers case.

Roberts is a conservative with four other Republican appointees on his right, including Justices Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh, Trump’s two appointees. He wrote the 5-4 ruling last year upholding Trump’s travel ban and said then the immigration laws entrust enforcement to the chief executive.

In what may be preview to how they view the Dreamers case, Roberts and the court’s other conservatives in 2016 blocked a similar but more sweeping Obama order, which would have protected as many as 4 million people who were living illegally in the country.

And in recent months, the chief justice played a key role in two other immigration victories for Trump. In late July, a 5-4 majority including Roberts overturned a federal judge in Oakland and cleared the way for Trump to shift $2.5 billion of military construction funds to pay for a border wall. In September, the court overturned a federal judge from San Francisco and let Trump enforce a new ban on asylum claims at the southern border from migrants who did not seek asylum in Mexico.

Those two cases were decided as emergency orders and without a full opinion. They reflect what has become the familiar pattern since Trump took office. The ACLU and Democratic state attorneys have rushed to federal courts in California and New York and won a series of quick rulings that put Trump’s initiatives on hold. When the cases reached the Supreme Court, Trump and his lawyers have often prevailed.

But Roberts is emerging as one of the court’s most unpredictable votes, most famously siding with liberals twice to uphold the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare.

Conservatives were equally disappointed in June when Roberts joined with the court’s four liberals to block the Trump administration from adding a citizenship question to the 2020 census. The chief justice agreed the law gave Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross authority over the census, but he concluded nonetheless that the secretary had violated the Administrative Procedure Act by giving a “contrived” and “pretextual” reason for adding the new question. Hardly anyone believed Ross’ claim that he was seeking to better enforce the Voting Rights Act. Critics said it was designed to reduce census participation among Latinos.

That ruling, though highly procedural, has given hope to lawyers for the Dreamers. They include Ted Olson, a Republican and the U.S. solicitor general under President George W. Bush. He argued that when Trump terminated the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program in 2017, he did not give a valid explanation to justify the move. Federal judges in San Francisco, New York and Washington, D.C., agreed. They said Trump’s repeal rested on the false claim that Obama’s order was illegal from the start.

“The executive can change course on enforcement policies, but not in arbitrary and unreasoned ways,” he wrote. His brief argued that presidents for 70 years had used “parole” or “deferred action” to shield large groups of immigrants and refugees, including Hungarians in the 1950s, Cubans in the 1960s and Vietnamese and Cambodians in the 1970s. “DACA is lawful. The administration could have left [it] in place. It did not have to end this humanitarian policy that allows nearly 700,000 people to stay in the only country they have ever really known,” he said.

In November 2018, the 9th Circuit Court upheld a district judge’s order that had blocked Trump’s repeal.

UCLA law professor Hiroshi Motomura, an expert on immigration law, said the court’s opinion by Judge Kim McLane Wardlaw “reminds me very much of Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion in the census case.” Motomura said the judge ruled that DACA could be rescinded, but there had to be a valid reason articulated. The decision could not rest on the “erroneous premise” that DACA was unlawful, the judge said.

For his part, Trump has continued to insist President Obama’s order broke the law because it exceeded the powers of the president. It was a “totally illegal document,” he tweeted in September. Trump has noted that Congress could pass legislation to protect Dreamers. But attempts to do so have failed in the past, largely because Trump has insisted that Democrats also agree to accept new limits on legal immigration in exchange for the protections for Dreamers.

Trump’s Solicitor Gen. Noel Francisco has the easier argument in the high court. If Obama as president was free to grant temporary relief to the Dreamers, Trump as president is free to change course, he said. That is especially so for the chief executive’s “decision to rescind a discretionary policy of non-enforcement against a category of individuals who are violating the law on an on-going basis,” he wrote.

The National Immigration Law Center in Los Angeles says there are more than 700,000 DACA recipients here now. They arrived on average at age 7, have lived here more than 20 years and are the parents of 256,000 children who are U.S. citizens.

The DACA policy emerged from the Obama administration’s strategy to target criminals, drug traffickers, security threats and repeat border crossers for arrest and deportation. As such, it made no sense to go after young people who had been brought into the country as children and had clean records since.

In 2012, then-Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano issued a memo setting out the new policy and said it was based on “the exercise of our prosecutorial discretion.”

“Our nation’s immigration laws must be enforced in a strong and sensible manner. They are not designed to be blindly enforced without consideration given to the individual circumstances of each case,” she said. “Nor are they designed to remove productive young people to countries where they may not have lived or even speak the language.”

Those who were younger than 16 and had lived in the United States for at least five years were invited to come forward. If they passed a background check, they could be granted deferred action “on a case-by-case basis” and obtain a work permit.

A year later, Napolitano was named the president of the University of California system and she is one of the lead plaintiffs in the suits to preserve DACA. One of the three cases to be heard together Tuesday is called the Department of Homeland Security vs. Regents of the University of California.

“I hope the Supreme Court justices don’t lose sight of the lives that are at issue,” Napolitano said. “They are really American in every way. They have grown up here. They have succeeded here at UC. They are the kind of young people we want.”

Opinion polls have found more than three-fourths of those surveyed — Republicans as well as Democrats — said they favored granting permanent legal status to the Dreamers.

A year ago, however, the administration’s lawyers urged the high court to take up the issue and to uphold Trump’s repeal.

But the justices waited and took no action for months, perhaps hoping that Congress and the president would resolve the legal status of the Dreamers.

With no prospect of congressional action, the justices announced on the last day of their term in late June they would decide on Trump’s repeal of DACA.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.