What the #%&@?! Trump and 2020 Democrats are cursing a blue streak

- Share via

The subject line, targeting President Trump, was purposely provocative: A string of angry emojis and a call to “dump the *^*%#%/!!!!!!!”

“Sometimes,” read the email launching a progressive fund-raising drive, “cursing is required.”

Sometimes actually seems to be quite often, as the path to the White House has become a blue streak of vulgarity, cuss words and four-letter effusions.

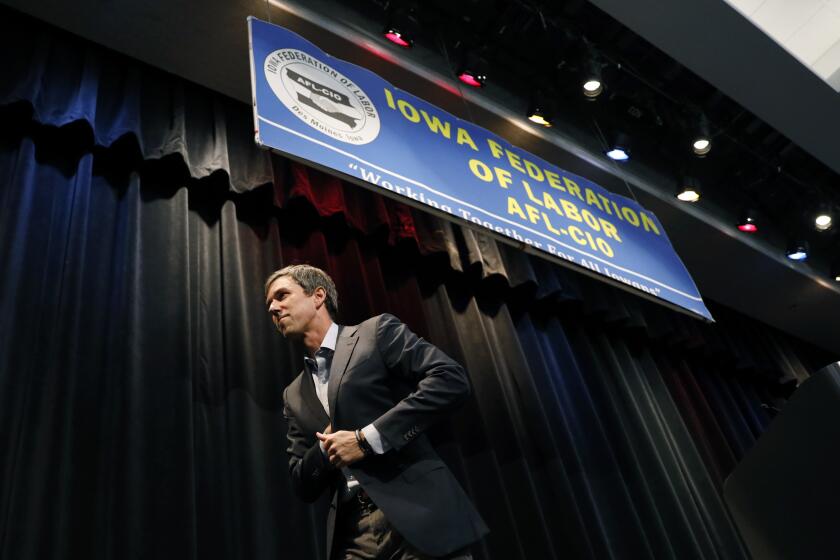

Trump and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker have employed a barnyard-related epithet numerous times. Montana Gov. Steve Bullock has offered a crude reworking of his campaign’s catch phrase, governors get stuff done. Former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke markets T-shirts echoing his profanely stated concern about gun violence and proudly boasts of his off-color vocabulary.

“I was talking to some people today,” he said during a recent stop in Los Angeles, “and somebody said, ‘I’m so glad that you say f—, because I say f—.’”

In the aftermath of the El Paso shootings, the 2020 Democratic presidential hopeful vows to follow a path less traveled as he crusades against President Trump and calls for stiffer gun laws and a more compassionate immigration policy.

The profusion of profanity, which has drastically increased during the 2020 campaign, stems from numerous factors, including the mores of a less decorous society, the cultural influence of anything-goes cable TV and the internet, and, not least, a president who began shredding political norms and behavioral boundaries the moment he launched his candidacy.

Because of Trump’s success, “politicians on both sides of the aisle are thinking, ‘Maybe profanity, which seems less scripted and guarded, is something I should try out,’” said Karrin Vasby Anderson, an author and political communications expert at Colorado State University.

Indeed, GovPredict, a public affairs software firm that aggregates data for trade groups and other clients, has found a notable rise in foul-mouthed political speech in the last five years and, especially, since the presidential campaign began in earnest this year. Researchers scouring Twitter found more than 2,400 uses of profanity by state and federal lawmakers so far this year — “jackass” and “crap” being the mildest of 13 epithets tallied — compared to fewer than 850 in all of 2018.

The cussing has become so contagious that ABC warned participants in the last Democratic debate there would be no broadcast delay, hence no time to bleep four-letter words. “Candidates should therefore avoid cursing or expletives in accordance with federal law,” the network urged. (Save for the odd “damn” and “hell,” the 10 spirited contestants complied.)

Other broadcasters and news organizations have had to relax their standards or find creative means of quotation to avoid offending their audiences.

It’s not as though politicians are national arbiters of good taste.

Columnist Judith Martin, who has spent decades defending standards of decorum and politesse under the pen name Miss Manners, said no one should look to elected officials to model upstanding speech or good behavior. “That would be pretty pathetic,” she said, though “not as bad as looking to rock stars and movie stars.”

Nor should the occasional — or not so occasional — curse word come as a surprise. Politicians are people, after all, and not plaster saints.

2020 presidential contender Andrew Yang wows his “YangGang” in L.A.

That said, the many indelicate utterances of President Nixon, famously rendered as “expletive deleted” in transcripts of his secret White House tapes, still held the capacity to shock when they were revealed nearly half a century ago.

Eyebrows arched in 2000 when George W. Bush, running for president, described a New York Times political writer as a “major league asshole” and again in 2010 when Vice President Joe Biden used an unprintable modifier — “this is a big f—ing deal” — to express his enthusiasm over signing of the Affordable Care Act.

In each of those episodes, however, the statements were meant to be private. Nixon appealed to the Supreme Court to fight public release of the raw tapes — along with their evidence of criminal wrongdoing — and Bush and Biden were both inadvertently caught speaking on hot microphones.

What’s different about today’s cursing candidates is the deliberate nature of their unrefined language.

Trump, a virtuoso at reading a crowd, cannot help but note the frisson of excitement at rallies when he employs “hell” for added emphasis, as in suggesting those in the country illegally need to “get the hell out” of the United States. (A word his pious vice president, Mike Pence, would never use.)

Trump’s use of the bovine epithet to impugn the White House investigation by special counsel Robert S. Mueller III went over so well at a gathering of conservative activists, the president repeated it days later on the campaign trail; soon a variant, #RidiculousBull, surfaced on Twitter.

The White House declined to comment on Trump’s use of profanity.

John Murphy, an expert on political rhetoric and its evolution, sees a degree of calculation in the cussing.

“It’s a way to say, ‘I’m so passionate about this issue it’s just bursting out of me,’” said Murphy, a professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “It’s a sign of authenticity: ‘I’m real.’”

O’Rourke suggested as much when asked recently about his not-infrequent dropping of f-bombs. Earlier this year, he forswore their use after being confronted by a concerned voter in Wisconsin.

“We already have one vulgar-in-chief,” said the man at a meet-and-greet in Madison. “Do we need to replace him with another?”

“Great point,” O’Rourke responded. “And I don’t intend to use the f-word going forward.”

That changed in the aftermath of August’s mass shooting in his hometown of El Paso, when the candidate fell back on his old speech pattern, offering four-letter commentary on both Twitter and national TV. In defense, he said the normal parameters of debate are too confining for these highly contentious times.

“Our political rhetoric and our language has really been insufficient in describing just what is happening in this country today and the threat posed by Donald Trump,” O’Rourke said after a heartrending tour of Los Angeles’ skid row. “I think the focus-group-driven, poll-tested triangulated careful language has kept us from seeing things for what they are, calling them by their true name.

“And when something’s f—ed up,” he said, “saying it’s f—ed up is really important.”

Kathryn Jones, who heads a digital media company for progressive organizations, the Collective Agency, offered the same crisis-mode justification for her provocative press release referring to the president as *^*%#%/!!!!!!!

“The idea of being nice and [politically correct] just feels useless and old news,” Jones said. “These past three years have been taxing on all of us, personally and politically, and now is not the time to be worried about who we’re offending.”

There is, however, a risk of backlash from voters accustomed to more dignified language and comportment from those who aspire to sit in the Oval Office.

Judging from her 90-year-old mother, for one, Penn State’s Mary Stuckey believes older voters are far more likely to cringe than thrill to the sound of a White House contestant in unexpurgated flight.

“She’s used to my potty mouth. But she doesn’t want to hear it from her president,” said Stuckey, who studies political communication and campaign rhetoric. “Many people would prefer their professionals to be professional.”

Other experts agreed.

“Right now ‘appropriate’ and ‘authentic’ are in a war,” said Murphy, hoping his preference for the former doesn’t make him “sound like an old fuddy-duddy.” (He’s 59.)

But it seems as though the generation gap, a cultural touchstone of the 1960s, is alive and well.

O’Rourke, 46, recalls being admonished during his 2018 Texas Senate campaign by a woman who brought her grandson to a campaign stop in San Antonio and asked the candidate to stop swearing. “It really turns people off,” she said.

As they were leaving, he recounted, the young man turned and offered his advice. “Keep it up,” he whispered.

Times staff writer Michael Finnegan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.