Does a billionaire have a place in the 2020 Democratic field?

- Share via

It would seem that San Francisco billionaire Tom Steyer belonged in America’s highest tax bracket in 2010. He and his wife Kat Taylor reported $149 million in taxable personal income, well beyond the $374,000 that required many other taxpayers to pay 35%.

But the couple paid less than 26% in federal taxes, taking advantage of rates that are lower on investment income than they are on wages. They took nearly $27 million in itemized deductions on $175 million in gross income.

Steyer, a former hedge fund manager now running for the Democratic presidential nomination, has been a major beneficiary of tax breaks that favor the rich, according to tax returns that he recently made public. In a race against rivals who have put growing income inequality near the top of their 2020 agenda, that’s one of many potential sources of political trouble that emerged from the returns.

Most glaring is what was missing.

Like all U.S. taxpayers, Steyer and his wife were required to identify every source of their 2010 investment gains ($89 million), stock dividends ($16 million) and other income ($70 million).

But when Steyer recently released nine years of federal and state tax returns in what he called an unprecedented display of transparency, he withheld nearly every page that showed where all the money came from. His campaign spokesman, Alberto Lammers, declined to say why.

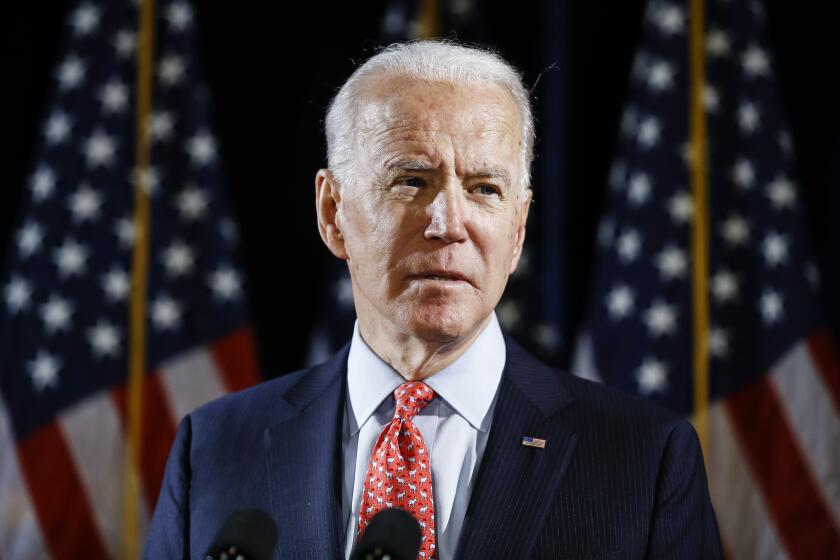

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

The vast scale of the omissions — the returns referred to more than 1,000 attachments that were sent to tax authorities but not released publicly — underlines some of the inherent challenges of his long-shot candidacy.

“I think the enormous gaps in his tax returns speak to the enormous vulnerability of a rich guy running on taking money out of politics,” said Lawrence Jacobs, a politics professor at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

Steyer, who has donated more than $500 million to candidates and political causes over the last decade and vowed to spend $100 million on his presidential run, argues that corporate money has corrupted the nation’s politics.

“We’ve had a corporate takeover of our federal government,” he told Fox News on Wednesday.

Jacobs, however, described Steyer as “a poster child for the way in which money has infiltrated our elections.”

“If he were to move out of the very bottom of the candidate rankings in the polls, he would find himself facing a withering assault” from rivals over his tax-return redactions, Jacobs said. “Frankly, the only reason that Steyer hasn’t been punched in the chops is that the leading candidates hope to be the beneficiaries of his largesse in the coming months.”

Steyer declined to respond to the criticism.

Steyer “made a disclosure that he felt was appropriate to give the public a view into his income and taxes paid,” Lammers said. “Tom has been clear that he invested in companies in all sectors of the economy and has never hid from that fact. That’s why he ultimately decided to leave his firm and focus on giving back.”

In 2012, Steyer stepped down as the top manager of Farallon Capital Management, the San Francisco hedge fund that he founded, and became one of the biggest donors to Democratic campaigns. He has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the fight against climate change and television commercials calling for the impeachment of President Trump.

When he voluntarily posted his tax returns online, Steyer did not disclose that he was withholding major portions of them.

The hidden parts detail investments that yielded hundreds of millions of dollars for Steyer. The omissions are especially significant because he had previously voiced regrets about making money in the fossil-fuel and private-prison industries.

“It’s kind of like having your cake and eating it too — ‘Oh, I’ve disclosed my tax returns,’ but not really,” said Meredith McGehee, the executive director of Issue One, a nonpartisan group that works to reduce the influence of big money in politics. “You want to get credit for it, but you didn’t really do it.”

Among the things Steyer’s omissions kept from the public were nearly all of the $267 million in federal and state tax deductions that he and his wife took from 2009 to 2017. One of the rare exceptions was for their 2010 donation of a 10-year-old GMC Yukon sport utility vehicle to a Ventura charity, Cars for Causes. Its value was $4,700.

The returns hint at Steyer’s extensive use of offshore tax havens, a practice long criticized by many Democrats.

While details of Steyer’s offshore investments were withheld, a memo released by his campaign argued there was nothing improper about that income.

“The fact that these are reported on his taxes demonstrates that the income passed through directly to Tom, was properly reported to the IRS, and all appropriate taxes were paid,” the memo said.

In 2012, President Obama’s reelection campaign pounded his Republican challenger Mitt Romney for refusing to release more than two years of his tax returns. Obama’s team portrayed Romney, who made a fortune in private equity, as a ruthless plutocrat who made millions of dollars in corporate takeovers that put thousands of Americans out of work.

Romney, whose federal tax rate dipped as low as 13% as he harvested the benefits of loopholes available to wealthy investors, had faced similar attacks four years earlier from Mike Huckabee, a rival in the 2008 Republican presidential contest. Romney “looks like the guy who fired you,” Huckabee said.

“It was a very sharp criticism that resonated with a lot of working-class voters inside the Republican primary electorate,” said Kevin Madden, a top Romney adviser in the 2008 and 2012 campaigns.

For now, Steyer’s Democratic opponents are for the most part ignoring him. When he entered the race, Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts each suggested billionaires should not be able to buy their way into the White House.

Should Steyer’s plans for heavy television advertising succeed in turning him into a more viable contender, the concerns raised by ethics watchdogs could be picked up by his rivals and turned into campaign attacks.

“If he’s trying to distinguish himself from others as being more transparent,” said Ann Ravel, a former Democratic chairwoman of the Federal Election Commission, “it’s a little disingenuous if the actual information about who’s behind this money is not disclosed.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.