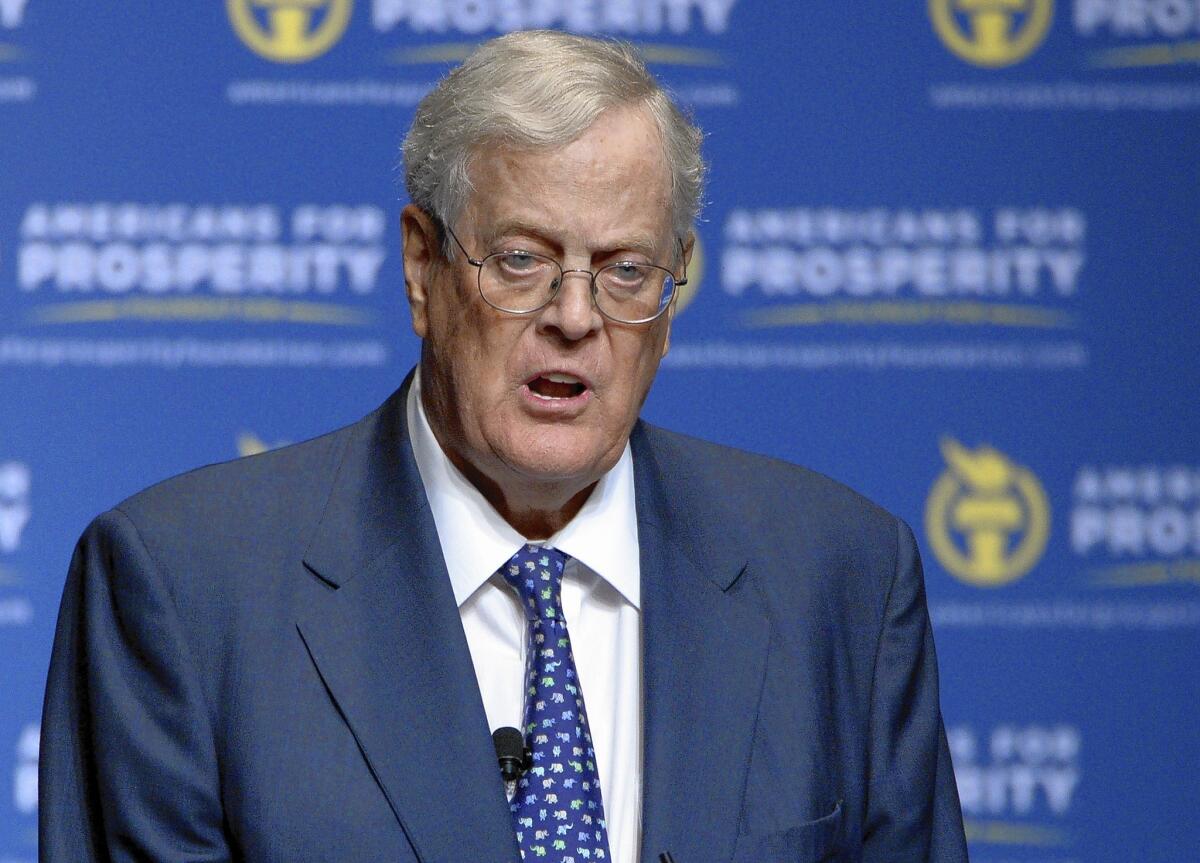

David Koch dies at 79. With brother, he moved U.S. politics to the right

- Share via

David H. Koch’s career as a politician was hardly illustrious, beginning and ending with a quixotic 1980 bid for the vice presidency, when Koch and Ed Clark, his running mate on the Libertarian Party ticket, tried to persuade voters that Ronald Reagan would leave the nation careening toward socialism.

But few Americans have had an impact on the political system to rival that of David Koch and his brother Charles.

David Koch, who died Friday at 79 after a long battle with prostate cancer, was the aide de camp to Charles, his older brother, as the two leveraged the family fortune, one of the nation’s largest, to push American politics to the right. Charles Koch, 83, announced his brother’s death in a statement.

The Koch brothers notched huge and lucrative victories over the political system and American government, remolding large parts of the Republican Party, pushing the boundaries of dark money in politics, and fueling a potent backlash against environmental regulation and government programs as disparate as healthcare and mass transit.

While David Koch often played the role of passive investor in the ideological battles launched by his brother, his support for the cause was unyielding and enabled the unfettered expansion of the Koch political empire.

“David shared Charles’ vision for the company and the politics,” said Christopher Leonard, author of the recently published “Kochland: The Secret History of Koch Industries and Corporate Power in America.”

“He was fully on board.”

The behind-the-scenes efforts of the Koch brothers nurtured the tea party movement after the election of Barack Obama as president, fueled climate denialism, and won legal victories that allowed wealthy donors to spend unlimited amounts on political campaigns.

The movement the brothers set in motion remains in full force even in David Koch’s absence, but his death raises the question of who will eventually inherit it from his brother, who continues to preside over the family enterprises.

“The political mantle is up in the air,” Leonard said. “It is an open question whether it will continue as it has.” Some have speculated that Charles Koch’s son, Chase, would eventually run the network, but “Chase is not the driven, intense builder that his dad has been,” he said.

The notable deaths of 2019 include Ross Perot, Luke Perry, Nipsey Hussle, Gloria Vanderbilt, João Gilberto and Doris Day.

David Koch was one of the world’s richest people, with assets of more than $42 billion when he died. The worldview he and Charles shared was shaped by their father, Fred, an ardent anti-communist who made his fortune improving the process for refining gasoline and construction of refineries throughout Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, and became a cofounder of the right-wing John Birch Society.

Fred’s sons would inherit Koch Industries, based in Wichita, Kan., and expand it into a chemical and fossil-fuel behemoth with more than 100,000 employees. The firm was constantly at odds with regulators, paying millions of dollars in fines and court judgments.

While the more reserved Charles Koch has been the mastermind behind the movement the brothers would build, David was often a public face of the Kochs, carving out a place for himself on the Manhattan society-party circuit and donating hundreds of millions of dollars to the city’s arts and medical institutions.

The brothers formed an alliance amid a legal war with their two other siblings over distribution of the Koch Industries proceeds, and David Koch would be a loyal lieutenant to his brother, Leonard said.

They shared a fierce antipathy toward government, with much of their political and charitable giving aligned with their business interest in rolling back regulations, cutting taxes and shrinking bureaucracy.

The brothers would ultimately invest hundreds of millions of dollars into an innovative and wildly successful approach to reaching their policy goals, one that involved a network of hundreds of other wealthy anti-government activists, armies of attorneys and lobbyists, and the seeding of grass-roots activist groups across the country.

By the time of the Obama presidency, the Koch network rivaled the union movement in its political largesse and influence. Their movement gained further strength with the Supreme Court’s landmark Citizens United decision in 2010 that opened the way for corporations, the wealthy and other interests to spend unlimited amounts on politics. The Koch brothers helped bankroll the case as it went to the high court.

By January 2014, the Washington Post reported that the Koch network was stealthily funding 17 different conservative groups and had poured at least $407 million into the previous elections to defeat Obama and other Democrats. It was operating at an unprecedented level of secrecy, with funds funneled through limited liability corporations and opaque nonprofits created to shield donor disclosure.

The opacity of the network became a flashpoint in California during the 2012 elections when regulators took aim at $15 million that one Koch-affiliated group poured into an unsuccessful effort to help defeat a tax hike on the ballot and help pass another measure limiting union clout.

State officials said the contributions ran afoul of California disclosure laws. They ultimately tracked down and revealed the names of the wealthy individuals who had attempted to secretly fund the effort and levied millions of dollars of fines.

The Koch operation went far beyond investments in election-cycle infrastructure and ideological think tanks. Koch-affiliated groups such as Americans for Prosperity and the American Legislative Exchange Council actively organized at the state and local level to push the broader conservative agenda. They have incubated and trained activists and politicians who worked their way through the system.

The American Legislative Exchange Council grew into a sophisticated tool for the right, with expert attorneys drafting anti-regulatory measures favored by Koch allies and recruiting lawmaker members to lobby for them in the states. Americans for Prosperity mobilized members at the local level against policies including renewable energy mandates and public transit programs. The group mounted a formidable effort to roll back policies enabling the expansion of solar energy in several states.

Many alumni of the Koch network occupy key posts in the Trump administration.

Although the brothers have been openly critical of President Trump and his policies on trade and immigration, on which he has departed from their free-market and small-government views, many of the far-reaching regulatory rollbacks Trump has been able to achieve are the result of Koch investments and political alliances.

The administration is populated with graduates of the Koch network at the highest levels. Vice President Mike Pence has deep ties to the Kochs, as does Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. Former Environmental Protection Agency chief Scott Pruitt is also a longtime Koch network ally.

Marc Short, the former White House head of legislative affairs and currently Pence’s chief of staff, was once a key operative of the Koch network.

The advocacy group Public Citizen in November 2017 identified 21 officials in the White House or awaiting confirmation for White House posts who had either worked for groups in the Koch network or represented Koch businesses or Koch-affiliated political groups as attorneys or lobbyists.

Around the time that report was published, the Koch network released a memo to donors touting two big achievements, Leonard noted in his book.

The first was the Trump tax-cut bill, which the Koch network had infused with its own priorities with the help of its many allies in the Congressional Freedom Caucus. The other victory: the regulatory rollbacks Pruitt and others championed, including the withdrawal by the Trump administration from the Paris climate accord.

“We’ve made more progress in the last five years than I had in the previous 50,” Charles Koch told his allies.

Brown is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.