Two years and thousands of bills later, here are the California Legislature’s wins and losses

- Share via

California’s 120 legislators took the oath of office in December 2014 with pledges to tackle issues like the cost of a college education, the state’s minimum wage and beyond.

So how did they do?

On Wednesday, the final gavel fell on the two-year session of the California Legislature, which saw the introduction of more than 5,000 proposed laws, resolutions and constitutional amendments.

Legislative leaders have praised efforts on a variety of important issues, while admitting that a few big items were left unfinished.

Big battles over climate change end with wins — and scars — for Democrats

Some of the biggest headlines were made by new efforts to combat climate change, all building on the 2006 law to shrink California’s carbon footprint. But it came at a price, as Democrats backed by labor and environmental groups clashed with Democrats aligned with business interests.

The flash point came in 2015 as the business-backed Democrats balked at a plan to slash gasoline use in California, leading more liberal party loyalists to accuse those legislators of being in the pocket of the oil industry.

Those same skeptical Democrats demanded this summer’s climate change proposal include new legislative oversight of the state’s powerful Air Resources Board, insisting that environmental protection efforts focus more on the impact to poor communities. Even though compromises were inked, the schism inside Democratic ranks caused by these two years of fights are unlikely to heal anytime soon.

Emotional votes on aid-in-dying, new vaccine mandates for school kids

Lawmakers struggled at the start of the session with the medical and moral issues surrounding the rights of the terminally ill to end their own lives. After rejecting an aid-in-dying bill in the early summer of 2015, Democrats brought the issue back for a second try and Gov. Jerry Brown signed the new law, which took effect this past June.

No less controversial was Senate Bill 277, which limited the allowable exemptions to California’s vaccination requirements for public school children. Vaccine critics first tried to overturn the law, seen as one of the nation’s most aggressive vaccination efforts, through a statewide ballot referendum. When that failed, a lawsuit was filed. It remains pending.

Legislative gridlock over California’s transportation crisis

Few failures of the legislative session were as prominent as the failed negotiations on a broad, long-lasting fix to the state’s transportation woes. In June 2015, Brown called a special legislative session on transportation, which ran concurrently with the regular work at the Capitol. But even after several proposals were floated and then reworked, the discussion struck out when it came to raising the state’s gasoline tax to help pay for a portion of the plan.

Tax increases require a supermajority vote in each house, and Republicans were unwilling to put up the needed support. As such, it wasn’t surprising that GOP lawmakers also balked at the most recent proposal, a $7.5-billion plan by Democrats that included raising the gas tax by 17 cents a gallon. The proposal also relied on an even bigger diesel tax increase and new fees to register electric vehicles.

In part, the transportation standoff has seemed stuck on a broader debate about how best to fund road and highway repairs in an era where gas tax revenues are dwindling because of increasingly fuel-efficient vehicles. Regardless, both Democrats and Republicans have criticized each other for failing to act. That doesn’t bode well for those who still hope lawmakers will take the rare step of returning to Sacramento after the Nov. 8 election for a brief lame-duck legislative session focused on the issue.

Budgets were on time, voters helped boost long-term savings

Lawmakers continued the relatively recent practice of passing on-time state spending plans during this legislative session, as they confronted growing concern that California’s relatively strong economic recovery might soon come to an end.

Brown pushed lawmakers to craft a new, more robust cash reserve account that would attempt to sock away some of the windfalls generated by capital gains income taxes paid by California’s highest earning taxpayers. Voters ratified the plan as Proposition 2 in 2014 but the new cash reserve rules only kicked in during the latest legislative session. By next summer, it’s estimated those reserves will total $6.7 billion.

Even so, legislators largely gave the governor what he wanted during budget negotiations — because, in part, those budgets relied on the revenue projections crafted by Brown’s own advisers. In 2016, Democrats celebrated the victory of restoring some funds to families on welfare assistance. And a bipartisan group of legislators came together to revamp a tax on health insurance plans that accounts for an important part of the funding for the Medi-Cal program for poor families.

Democrats also took pride in a $2 billion bond to provide housing help for homeless Californians suffering from mental illness. And it was during budget negotiations when lawmakers made good on the fight against tuition hikes at University of California and California State University campuses, linking additional school funding to promises of keeping in-state tuition flat.

Sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter »

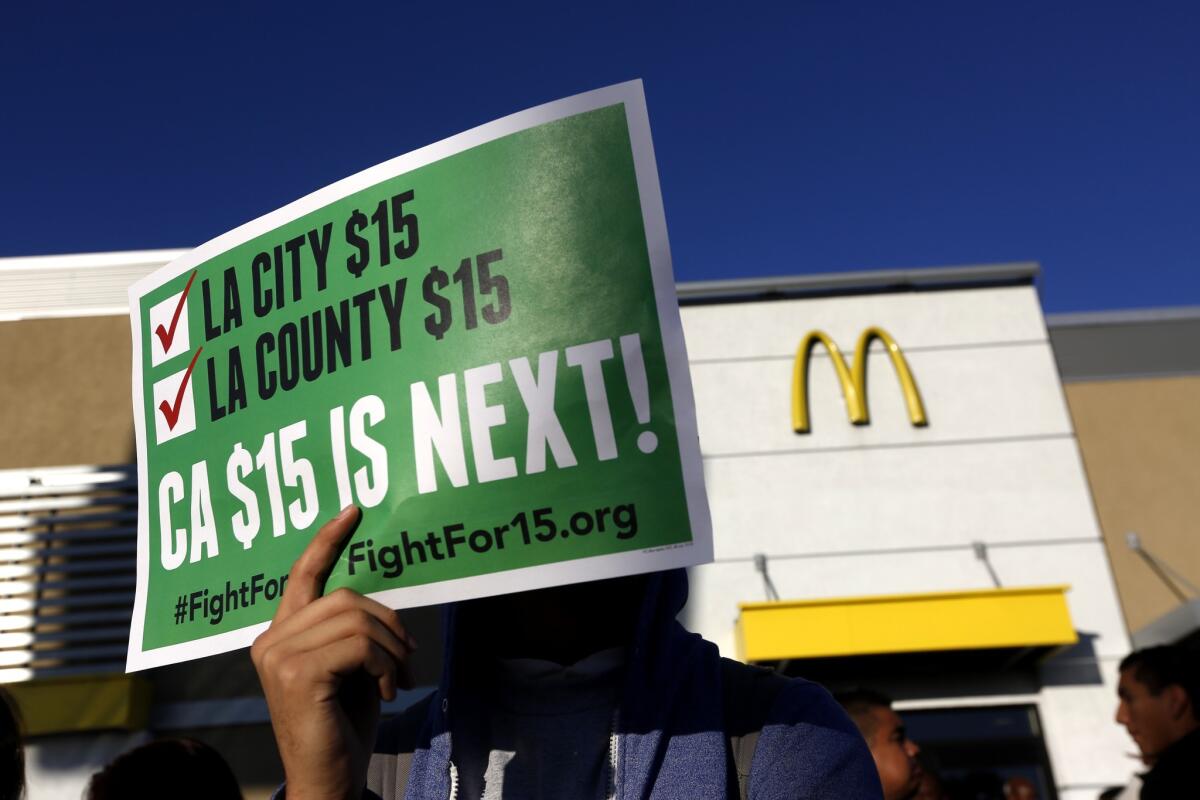

The threat of a ballot fight over minimum wage sparked Capitol action

While lawmakers promised in late 2014 to take another look at the state’s minimum wage, it took the threat of a Nov. 8 ballot initiative to force action at the Capitol.

In April, the first of two labor-union initiatives qualified for the ballot to impose a $15 an hour statewide minimum wage. Within days, Brown and legislative leaders huddled to craft an alternative way to reach that amount, and both unions agreed to stand down.

That deal will boost the wage to $10.50 an hour next year and then gradually raise it to $15 by as early as 2022. Few believe the impetus for the agreement would have existed if not for the looming ballot measure campaigns. And even that wouldn’t have happened if not for a 2014 law that allows initiative backers to withdraw their measure at the eleventh hour if their policy issue is handled instead by lawmakers in Sacramento.

Gun control efforts find some new common ground between lawmakers and Brown

The two-year legislative session saw a substantial focus on gun and ammunition laws, an issue brought back to the forefront at the halfway point of their work by the San Bernardino shootings on Dec. 2, 2015.

Senate leader Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) led the effort to require background checks for purchasers of ammunition as well as a ban on ammo magazines that can hold more than 10 rounds. Lawmakers also convinced the governor to agree to new restrictions on some semiautomatic weapons.

But Brown vetoed a spate of other bills, including an effort to remove guns from people deemed to be a danger. And even with the legislative action, an initiative similar to some of the new gun laws will appear on the Nov. 8 ballot as Proposition 63.

A judge asked lawmakers to take a look at teacher tenure, and they took a pass

Months before the beginning of the legislative session, a Los Angeles judge ruled in favor of a group of students who said that California’s teacher tenure and other job protection laws had deprived them of their constitutional right to an education. In the Vergara vs. California ruling, the judge urged lawmakers to take action themselves rather than leave the issue to the courts.

But a handful of overhaul proposals met fierce resistance in the Legislature, opposed by the politically powerful California Teachers Assn. The defeat of one bill in particular — seeking to add new criteria on student achievement to teacher evaluations — drew a sharp response from its author, Assemblywoman Shirley Weber (D-San Diego).

“If we are not about the business of improving the lives of children in multiple ways, then what the hell are we doing?” the former educator asked in a 2015 committee hearing.

A different bill, to make teacher tenure decisions after three years on the job instead of two, was defeated in committee this June.

A new era of legislative term limits began to take shape

Voters agreed in 2012 to relax term limits for legislators to allow up to 12 years in either house. And those new lawmakers are now a major political force in the Capitol.

In March, Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Paramount) took office with the potential of serving longer than any Assembly speaker in the last two decades. And in this summer’s Assembly floor debate over climate change bills, the new Democrats made clear that longer term limits mean they can stay engaged on how the policy actually pans out.

“This is not the last step,” said Assemblywoman Autumn Burke (D-Marina del Rey). “We will be here to continue to make more steps.”

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

ALSO:

See how you’re impacted by new California laws for 2016

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.