California passed a law boosting police transparency on cellphone surveillance. Here’s why it’s not working

A California law requires law enforcement agencies to seek permission at public meetings to buy the devices. (Aug. 28, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

- Share via

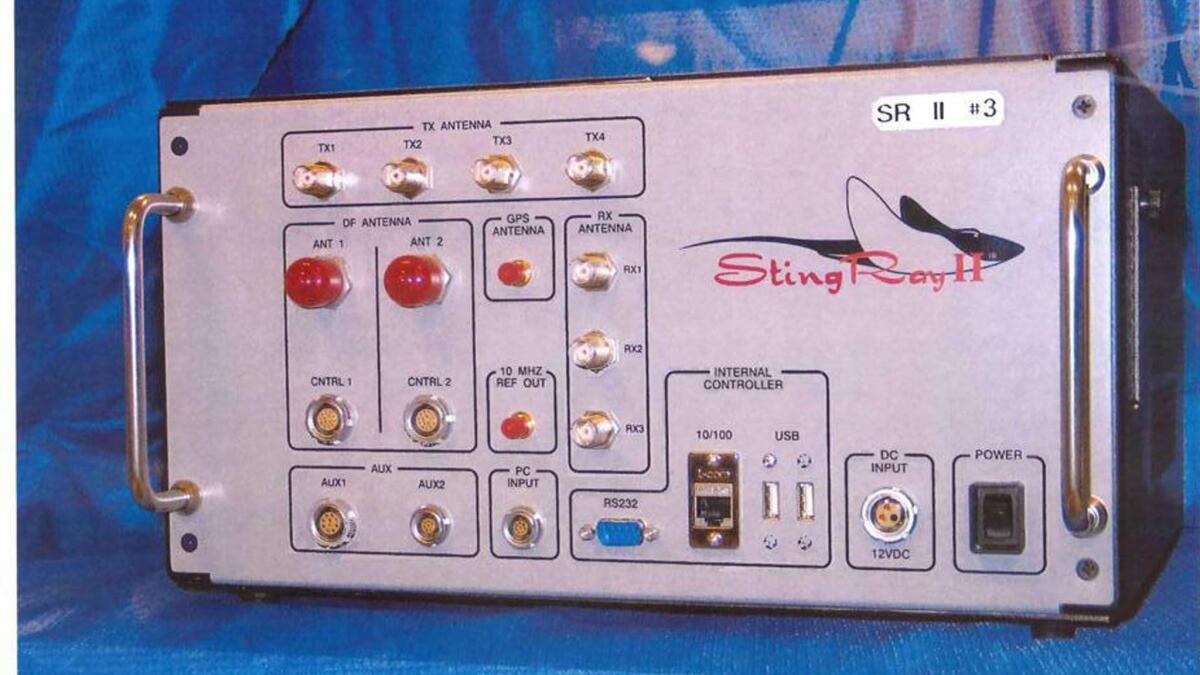

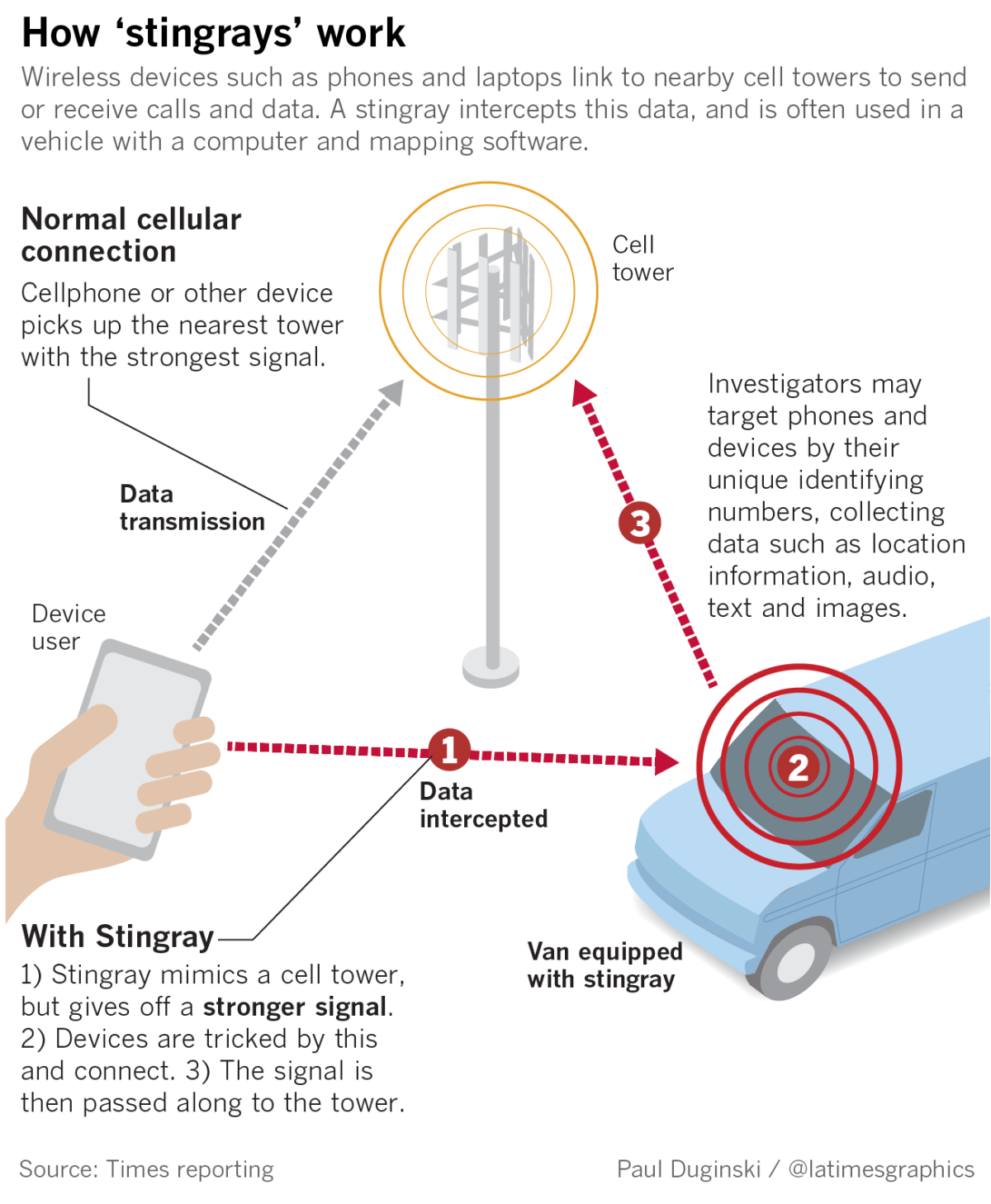

Several years ago, little was known about the StingRay, a powerful surveillance device that imitates the function of a cell tower and captures the signals of nearby phones, allowing law enforcement officers to sweep through hundreds of messages, conversations and call logs.

The secrecy around the technology, which can ensnare the personal data of criminals and bystanders alike, spurred lawsuits and demands for public records to uncover who was using it and the extent of its capabilities. In California, a 2015 law requires law enforcement agencies to seek permission at public meetings to buy the devices, and post rules for their use online.

But a Los Angeles Times review of records from 20 of the state’s largest police and sheriff’s departments, plus the Alameda County district attorney’s office, found some agencies have been slow to follow or have ignored the law. Several that partner with federal agencies to work on cases are not subject to the law’s reporting requirements. The result is that little information on StingRay use is available to the public, making it hard to determine how wide a net the surveillance tools cast and what kind of data they gather.

Who has stingrays

Out of 21 law enforcement agencies surveyed, 12 were found to own or have access to a StingRay or similar device. Nine of those agencies had developed and released online public polices.

| Department | Device | Policies |

|---|---|---|

| DepartmentLAPD | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

| DepartmentLong Beach Police | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

| DepartmentL.A. County Sheriff | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

| Department | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

| DepartmentSan Jose Police | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

| DepartmentFresno Police | DeviceACCESS** | PoliciesNO |

| DepartmentSacramento Police | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

| DepartmentSacramento County Sheriff | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

| DepartmentOakland Police | DeviceACCESS** | PoliciesYES |

| DepartmentAlameda district attorney's office | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

| DepartmentSanta Ana Police | DeviceACCESS** | PoliciesNO |

| DepartmentAnaheim Police | DeviceOWN | PoliciesYES |

**Officers don't operate the stingray but work with other agencies that may

Source: L.A. Times review of public records

The Times reviewed more than 400 documents it received from public information requests, including grant proposals, purchase orders and memos on the use of StingRays and similar devices generically called “stingrays” or “dirtboxes.”

The devices, which cost between $242,000 and $500,000, are primarily marketed for preventing and responding to terrorist threats, but the documents suggest they are used most frequently in felony criminal cases, such as burglaries, murders and kidnappings.

Out of 21 law enforcement entities The Times surveyed, 12 either owned stingrays or used or had access to them through partner agencies. Nine owned the surveillance devices, and each of them posted public policies online as required by law. Three of the nine went a step further to conduct annual reporting audits that showed when and in what cases the devices were used.

But some stingray policies posted by the law enforcement agencies revealed little about the devices besides noting they were in use. Other agencies took months to post their stingray guidelines online. The Los Angeles Police Department, which owns a stingray, updated its public safety policies to include its stingray guidelines only after questions from The Times.

Data on stingray purchases and use have long been difficult to come by, a problem the 2015 law requiring more public accountability was meant to correct — and has yet to fix.

The Times found that the nine agencies that own stingrays bought them between 2006 and 2013, mostly with federal grant money or under programs or agreements that prohibited any public disclosure, following a national trend. Local tax dollars weren’t used on the purchases, and city and county officials didn’t ask about them in a public forum.

Just two of the 21 law enforcement agencies polled by The Times have ever publicly discussed buying new devices before city or county officials: Santa Clara (which did not buy a device) and Alameda counties.

And only one agency, the Oakland Police Department, has gathered input from the public to develop guidelines for stingray use, which isn’t required under the 2015 law.

“Any tool can be used for good or bad,” said Brian Hofer, chairman of Oakland’s Privacy Advisory Commission, which helped establish the surveillance policies. “This is the most controversial piece of equipment that we know about, and they should not be used in the dark.”

A device cloaked in secrecy

Stingrays tend to be the size of small briefcases and mimic the function of cell towers. They give off the strongest wireless signal in an area, tricking nearby phones, tablets and laptops to connect.

Investigators can target the location data of specific phones, allowing them to track suspects and their associates. They can also sweep up communications over a wide area. How much and what types of data they collect — location information, audio or images — depends on how the devices are designed and how law enforcement agencies use them.

The technology has been used for about 20 years by federal, state and local law enforcement, often secretly, under manufacturer agreements that typically prohibit agencies from disclosing the purchases.

The public did not learn about the existence of the equipment until 2011, after an inmate in federal prison, Daniel Rigmaiden, spent three years scouring government records and meeting transcripts on a hunch that investigators used some kind of secret device to catch him.

Rigmaiden, a native of Seaside, Calif., who hadn’t had a stable living situation, was arrested in Phoenix for filing fake tax returns. Police were able to find him through tracking an old Verizon wireless card he seldom used to connect online.

“It wasn’t just that [investigators] were able to get historical call data from Verizon,” said Linda Lye, an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, which filed an amicus brief in support of his case. “They were able to pinpoint him to a particular apartment in a particular apartment building, which was far more precise.”

State bill requiring California police to disclose surveillance equipment clears its first hurdle>>

In 2015, California lawmakers passed the sweeping Electronic Communications Privacy Act, which prohibited any investigative body in the state from forcing businesses to turn over digital communications without a warrant. That same year, state Sen. Jerry Hill (D-San Mateo) introduced legislation to compel local law enforcement agencies to disclose more information about the use of stingrays in California.

“Our country has a rich history of democracy and civilian oversight,” Hill told a Senate judiciary committee that May. “The stealthy use of these devices undercuts the very nature of our government.”

The law, which took effect in January 2016, requires cities and counties that operate a stingray to create guidelines for how and when officers use the equipment. Any agency that wants to buy a device must first receive approval at a public hearing.

Opening access to information

The state law helped open up some public access to information about how and where the devices are used. Privacy advocates and lawyers have kept up the public pressure in some cities and counties, particularly in the Bay Area, calling on officials to put ordinances and guidelines in place to bar police from collecting data from those not under investigation.

Under most of those policies, officers can use the technology only when it is critical to a case and is approved by higher-ranking officers, or in emergency situations such as natural disasters. Investigators are also required to obtain search warrants. Any data not considered official evidence can’t be sought, recorded or stored. Officers must delete or destroy all information gathered by the equipment related to an investigation at the end of the period in which they’re authorized to use the technology.

Three agencies keep track of when officers use a stingray — the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, the San Jose Police Department and the Alameda County district attorney’s office. But their data offer few details about the cases.

In Los Angeles County, a report from the sheriff’s office showed deputies followed state law and obtained a search warrant in nearly all 138 investigations that required a cell site simulator in 2015, and 38 investigations in 2016, the majority of which were murder cases.

In that time, the device helped officers arrest 70 suspects and find one crime victim. Sheriff’s Department officials declined to disclose further information or records on those cases.

The Alameda County district attorney’s office, which purchased a device to be operated by the Sheriff’s Department and other area police agencies, said the stingray had not been used as of January.

The San Jose Police Department bought a $500,000 stingray in June 2013, and used it about 20 times between early September 2016 and June 2017.

Law enforcement officers in Oakland and San Jose, as well as several other California cities, say the law requiring them to disclose use of the devices has allowed them to ease community fears over what the technology can and can’t do.

“You watch TV and you’d think that we are sucking their phones dry of all the images, of all the texts, of all the pictures and emails,” said San Jose Police Lt. Steve Lagorio, who crafted guidelines for stingray use with the city attorney’s office. “But we are not. We don’t have that capability.”

The cellphone interceptor at his department is strictly used to target the phones of individual suspects, and Lagorio said he doubted any local law enforcement agencies used the equipment to do much more than that.

Calls for oversight

Privacy advocates and lawyers say a state agency is needed for oversight to ensure law enforcement agencies are following the law and post their own guidelines.

Most of the records on purchases and grant proposals reviewed by The Times were highly redacted, providing little insight into how their equipment is designed and what it can collect.

The LAPD provided purchase orders and invoices that show the department first obtained price quotes for stingray equipment in 2004, but it is unclear when it acquired the technology. LAPD officials said only that the stingray was not deployed due to technical malfunction issues, but declined to elaborate.

Other records from the Police Department show it obtained another stingray in June 2012, but the department declined to release additional information on the purchase, including its cost.

It was used more than 21 times in routine criminal investigations over four months in 2012, according to LAPD records that were first obtained by the First Amendment Coalition, a nonprofit that works to advance free speech and open-records laws.

In response to an information request regarding its purchases of stingray devices, the San Francisco Police Department provided heavily redacted records, including a 2012 grant proposal and shipping receipt showing the purchase of “specialized surveillance equipment” in 2007.

The department also gave The Times a document indicating a stingray was bought with 2009 federal grant funds. But a spokesman said the department did not have any public policies on the technology because the equipment was not in use.

Seventeen of the 21 agencies polled by The Times said they did not keep or declined to provide data on how often and in what types of cases they used stingrays.

Privacy advocates point to a loophole in the law that allows some law enforcement agencies to avoid reporting their use of the devices. Police departments that partner with another agency that owns and uses a stingray in an investigation are not required to publish their own guidelines for using the equipment.

The Santa Ana and Fresno police departments, for example, said they did not have any records on the use and policies of surveillance devices. But both departments acknowledge they work with agencies that do have them, including the FBI and the U.S. Marshals Service, and might have indirect access to the data they produce.

“Our officers don’t use the equipment, but we often look for fugitive hunters,” Santa Ana Police Cpl. Anthony Bertagna said. “Anaheim [police] may have one, the U.S. Marshals may have one.… They do help us catch fugitives, but whether they have one — you’d have to ask them.”

Increasing transparency

This legislative session, a new proposal by Sen. Hill would expand the state’s disclosure law on stingrays to all surveillance devices, including facial recognition software, drones and social media monitors.

Senate Bill 21 would require law enforcement agencies to disclose not only the use of the surveillance equipment, but the use of any information obtained from the devices.

Civil rights lawyers and advocates have supported the measure, saying transparency is necessary at a time when concerns over surveillance of immigrant and Muslim communities have risen under the Trump administration.

The legislation was narrowly approved by the state Senate, with heavy opposition from law enforcement officials who argued it would give criminals a road map to police agencies’ crime-fighting technology.

Its prospects of passage in the Legislature are unclear. Hill says he understands the technology has many benefits for law enforcement.

“[But] we need people — we need agencies — to be accountable, and we need civilian bodies to create that accountability standard,” he said.

—————————

FOR THE RECORD

6:31 a.m.: This article reported incorrectly that Daniel Rigmaiden was arrested in Phoenix. He was arrested in Santa Clara.

Twitter: @jazmineulloa

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.