California doesn’t have enough housing, and lawmakers aren’t doing much about it

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — The reason why California faces a housing affordability crisis is simple, many experts say: Lots of people want to live in the state and there aren’t enough houses for them.

“You don’t need a PhD in economics to understand this,” said Christopher Thornberg, an economist who recently published a report on state housing costs with the nonpartisan organization Next 10. “It’s basic supply and demand.”

The lack of housing supply fuels headlines that reveal the state’s housing problems at their starkest. It could explain why doctors and others making as much as $250,000 a year are struggling to find homes in Palo Alto. And why a firefighter in Menlo Park — home to Facebook — said he decided to commute four hours to work from Reno, Nev., because he was unable to find an affordable place nearby to maintain his standard of living.

This year, however, state lawmakers aren’t doing much to make it easier to build houses. Even those who have authored the handful of bills aimed at increasing the number of homes in the state concede their efforts only scratch the surface of the problem.

Legislators have shied away from tackling broad efforts to increase housing supply, such as overhauling the California Environmental Quality Act or reforming the tax code to incentivize residential development. Doing so would force lawmakers to take on some of the largest and thorniest policy issues in the Capitol.

“I think there’s more than the usual amount of politics around those issues,” said Assemblyman Richard Bloom (D-Santa Monica), who has introduced three bills this year to ease restrictions on homebuilding.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

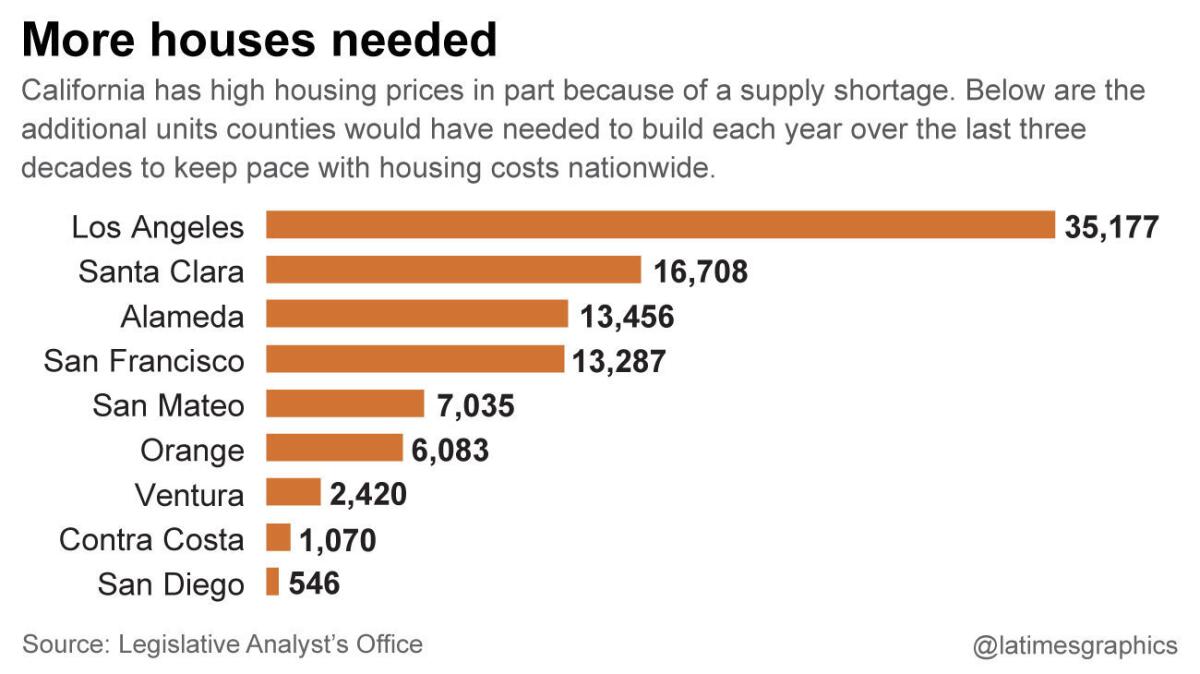

California finds itself in a deep housing hole, and residents are feeling the results. The state’s average home price of $459,000 is more than double what it is nationally. Over the last three decades, the state would have needed to build millions more new homes — including more than a million in Los Angeles County alone — to keep housing prices in line with the rest of the country, according to the independent Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The problem is especially acute in wealthy, coastal communities, many of which have seen strong job growth in the last five years as the economy has recovered without corresponding boosts in the housing stock.

“We’ve added almost half a million jobs in the Bay Area alone, and we’ve added 51,000 permits — not even buildings,” said Carol Galante, a professor of affordable housing and urban policy at UC Berkeley, who called the situation “out of whack.”

Instead of wide-ranging measures to spur housing development, lawmakers’ main response to the state’s housing crisis has been to try to increase low-income housing subsidies. Then-Assembly Speaker Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) tried and failed to pass a bill last year that would have added a $75 fee to many real estate transactions to fund affordable housing. Among this year’s highest profile efforts is a bid from Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) to borrow $2 billion to build housing for the homeless.

Though many experts believe that the state should funnel more dollars toward affordable housing — particularly after lawmakers took away a major funding source in 2011 by eliminating a program to redevelop blighted neighborhoods — greater subsidies won’t fix the problem. The legislative analyst’s report estimated that building affordable homes for the 1.7 million low-income households in California that currently spend half their salaries on housing would cost as much to finance each year as the state’s spending on Medi-Cal.

“You can’t tax your way out of a shortage,” Thornberg said of efforts to solely add housing subsidies. “It doesn’t work.”

In some ways, state lawmakers’ hands are tied on boosting housing supply because cities and counties primarily control building and permitting. But experts say the state could make many reforms to increase homebuilding.

Lawmakers could ease restrictions in the CEQA, the state’s primary environmental law, to allow for speedier and cheaper development, particularly in urban areas, experts say. Or they could allow sales taxes to be distributed by population instead of by commercial transaction, which may give municipalities an incentive to build more homes to increase their tax revenues.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Both ideas have been kicked around the state Capitol for years — legislators attempted a broad CEQA overhaul in 2013 — but have failed because the changes would upset numerous entrenched environmental, labor and business interests.

Beyond state-level politics, major changes to increase housing supply would also run into deep-seated local interests. State Sen. Bob Wieckowski (D-Fremont), who has authored a bill that would make it easier for homeowners to add additional units on their properties, said neighborhood groups fight increased housing supply because it often means greater density.

“People don’t like to use the ‘D’ word. They think of Cabrini Green in Chicago,” Wieckowski said, referring to the notorious housing project.

Economists worry that if lawmakers don’t fix the housing supply problems, many of the state’s efforts to improve the lives of low-income residents will falter. Many legislators cited high housing costs as a reason to boost California’s minimum wage to $15 an hour over the next six years. But unless something’s done to stem housing costs, much of that pay increase could be eaten up by higher rents, Thornberg said.

Bloom said he shares that concern. His three housing bills aim to make it easier to build an additional unit on a property, allow developers to build at greater density if they add affordable units, and reduce permitting requirements for properties already zoned for housing. All three, Bloom said, would make small increases to supply.

Bigger ideas to make it easier to build houses will have to wait, he said.

“These bills are hard enough to get through,” Bloom said. “They are not going to be a cakewalk. That’s the low-hanging fruit.”

Follow @dillonliam on Twitter

ALSO

Rent or own: Where can you afford to live?

Southern California apartment rents are expected to continue rising through 2018

California legislators propose spending $2 billion to build housing for homeless

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.