From the Archives: In Search of Elusive Justice

- Share via

Editor’s note: Kamala Harris announced her run for president on Monday. Here’s more background on the candidate in an article published in The Times on Oct. 24, 2004.

The girl on the witness stand was a 14-year-old runaway with a bad attitude and a foul mouth. She wore too much makeup and showed too much skin. Although she had cleaned up for her courtroom appearance, she still came across as hard and hostile. Kamala D. Harris, then assistant district attorney for Alameda County, was trying to convince a jury that the girl was the victim of a gang rape.

“Look, I know you don’t like her,” Harris recalls telling jurors. “And I know you don’t want her to play with your children. But the penal code was not created to protect Snow White. This kid is a child who needs to be protected from predators who are going to pounce.”

Harris won the conviction but lost the victim. The girl vanished, and a sketchy report suggested that she was selling sex in San Francisco. Harris and a district attorney’s inspector launched a search.

“We never found her,” Harris says.

That was 10 years ago. Harris, now the district attorney for San Francisco, is sharing grim stories on a sunny day inside a white-linen bistro on the Embarcadero called the Delancey Street Restaurant, the namesake operation of a nonprofit that helps ex-cons lead law-abiding lives. In this oddly apt setting, the tale of the victim who got away sinks in as a parable about the gap between a just verdict and the elusive nature of true justice. Tourists have no clue that their waiter, a few years earlier, would have sooner mugged them than serve the smoked trout. But they notice Harris and know she must be somebody, what with the warm greeting from Delancey workers and a few patrons.

These days, Harris (no relation to this writer) can’t help but make an entrance. She is a striking 39-year-old single woman with a radiant smile who is known for her intellect, work ethic and, as one attorney puts it, “the aura of her personality.” Her dramatic campaign to become San Francisco’s top law-enforcement official has made her a rising political star. While San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom has made international headlines with his high-profile, polarizing embrace of gay marriage, Harris may have the brighter future. At the Democratic National Convention, Harris served on the platform committee as an appointee of Chairman Terry McAuliffe, and she was a guest of honor at a reception hosted by House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi of San Francisco. Harris also addressed the black caucus, one of a group of women that included former Sen. Carol Moseley Braun and Sen. Hillary Clinton.

With an Indian mother and a Jamaican father, Harris strikes some observers as a California version of Barack Obama, the Illinois lawmaker of racially mixed heritage who keynoted the Democratic convention and is favored to be elected to the U.S. Senate. (Harris, incidentally, co-hosted a California fundraiser for Obama before the fame of the convention.)

Her blended heritage could well prove an asset in increasingly multicultural California, says Richard DeLeon, a political science professor at San Francisco State University. There is a lot of crossover appeal, DeLeon says, in a politician whose profile combines multiracial roots, feminism and strong law-enforcement experience. Open to debate, though, is how well that combination will play on a statewide or national stage.

On this day at Delancey Street, the district attorney is stylishly dressed in a pinstriped suit, high heels and a doubled loop of pearls. Who would play her in a movie? “Maybe someone like Halle Berry,” suggests one admirer.

But Harris says she wants nothing more than to be judged on her ability to deliver that elusive ideal of justice. She is in the vanguard of progressive reformers who say that California’s criminal justice system is in dire need of drastic change. Capital punishment, three strikes, determinate sentencing — the crackdown mentality, Harris says, has backfired badly, creating a massive adult and juvenile prison system that has absorbed billions of dollars of resources that would be more wisely invested on crime prevention and rehabilitation.

Only in San Francisco could a liberal such as Harris — who resists that label — run to the right of the incumbent. Former San Francisco Dist. Atty. Terence Hallinan had been a progressive iconoclast known for his battles with the San Francisco Police Department and Mayor Willie Brown. Harris promised to bring greater professionalism and competence to a hidebound public law office that was mired in the acrimony of the city’s political culture. “The greatest challenge for a district attorney,” Harris declared in her inaugural speech in January, “and the most serious work for us as a community, is the struggle to give meaning to justice. Let’s put an end right here to the question of whether we’ll be tough on crime or soft on crime. Let’s be smart on crime.” Which is, at least, a nice slogan.

Harris quickly won admiration in her new post. Assistant Dist. Atty. Linda Klee is encouraged that of the five district attorneys she has worked under in 33 years Harris “is the first who actually did the same job I do.” The others were lawyers, but none had been a regular prosecutor in the criminal court, a fact that speaks volumes about San Francisco’s unconventional politics. Harris recruited former colleagues from the respected Alameda County District Attorney’s Office to be her chief deputy and chief of investigations, and she brought in a new office manager to help modernize operations. Finally, the prosecutors have e-mail. Klee also is impressed that Harris is the first district attorney in three decades to get a fresh coat of paint on the entire office, not just her own quarters.

three months after her election, harris faced her first great political test when Police Officer Isaac Espinoza was gunned down with an AK-47. Only three days after the murder, Harris announced that her office would not seek the death penalty for the suspect arrested in the killing. Harris had made no secret of her opposition to capital punishment, yet she had still won the endorsement of the San Francisco Police Officers Assn. But her refusal to make an exception for Espinoza’s killer angered the police and many others.

Harris grimaces when asked about Espinoza’s funeral service, which transformed St. Mary’s Cathedral into a political theater. It happened to be her 100th day in office, and Harris sat in a front-row pew. Uniformed police officers and other mourners filled the sanctuary to overflowing. When Sen. Dianne Feinstein was introduced, it seemed likely that she would continue with her crusade against assault weapons. Instead, Feinstein called for the death penalty in this case, winning a standing ovation from police and blindsiding Harris. Later Feinstein said that if she had known that Harris opposed capital punishment, she probably wouldn’t have endorsed her.

Harris’ decision in the Espinoza case is “something people are still talking about,” says Barbara Meskunas, president of the Coalition for San Francisco Neighborhoods. “When you see the rising murder rate in this city, I’m not sure that sends the best message. You can respect her for sticking to her principles, but at some point you have to have respect for the law. You have exceptions for people who murder police officers. You have to go the distance.”

Harris declines to discuss the funeral and the controversy, as if it’s a wound that hasn’t healed. California law presents a dilemma for this progressive district attorney who, though she is too politic to phrase it this way, clearly considers the death penalty dumb on crime.

“I have wrestled with it. Absolutely I have wrestled with it,” Harris says. “I have thought, what if somebody killed my mother? What if somebody killed my sister? My niece? I’d want to kill them. I’d want them dead. It’s a natural human emotion. As someone grieving, I’d want vengeance.”

But Harris points to studies showing that capital punishment is not a deterrent, that it is disproportionately applied across race and class, and that the court-mandated appeals process diverts millions of tax dollars from programs that would deter crime.

Yet Harris insists that her stated views and campaign vows do not compromise her legal duty to consider the applicability of capital punishment. “I will review every case. I will review every case,” she says. Repetition is Harris’ way of emphasizing a point. “I have a committee. It is not something I do alone.” Critics suggest that her mind is closed and these committees amount to a charade. When reviewing “the worst of the worst of the crimes,” Harris says, “it would be inaccurate to think the decision is made because of some knee-jerk reaction to the issue. It’s much more complicated.”

Kamala Davi Harris has always lived in a complicated world, navigating a path where perceptions and reality often conflict. Her mother remembers the patronizing tone of a well-meaning Head Start official in Berkeley who excitedly informed her that Kamala had been tested as highly intelligent: “You don’t understand — Kamala could go to college!” What Shyamala G. Harris understood was that this man assumed her daughter must be an impoverished girl from the rough side of town, not a privileged child of foreign graduate students whose academic pursuits led them to UC Berkeley.

Harris’ mother, the daughter of a high-ranking Indian government official, would earn a doctorate in biological sciences and become a well-published breast cancer researcher. She is now based at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratories and lives in a spacious condominium in a historic building overlooking Oakland’s Lake Merritt. Harris’ father, Donald, earned his doctorate in economics, joined the faculty of Stanford University and advised the Jamaican government on economic issues.

Shyamala insisted on giving her daughters names derived from Indian mythology, in part to help preserve their cultural identity. “A culture that worships goddesses produces strong women,” she says. A favorite family story begins with Harris’ parents pushing her in a stroller as they marched for civil rights, joining in the protest chants. After one march Shyamala innocuously asked, “What do you want, Kamala?” The toddler replied: “FEE-DOM!”

Harris was in elementary school when her parents divorced. She and her younger sister Maya saw their father on weekends, holidays and during the summer while Shyamala raised the children amid what Harris calls “the black intelligentsia,” with intense dinner-table discussions about the civil rights movement. Maya Harris is now director of the Racial Justice Project for the ACLU of Northern California. “When we were growing up,” she explains, “the notion of justice and public service and a commitment to civil rights were not abstractions. They were completely a part of our lives, of who we were and who we are.”

An academic nomad, Shyamala gave her daughters a worldly education, traveling frequently to visit family in India, the Caribbean and Europe. Harris attended high school in Montreal, while her mother taught at McGill University there and did research at the Jewish General Hospital. Shyamala had a strict rule for her girls: No TV unless you were also knitting or doing needlepoint. “This whole thing of multi-tasking was ingrained early on,” Harris says, laughing. Shyamala also steeped her daughters in family values that exalted education and public service. The girls looked to their Indian grandmother, Rajam, as a role model, impressed by her work for women’s rights. Rajam, now 81, keeps in touch with her daughter and granddaughters via e-mail. As Shyamala puts it: “Kamala comes from a long line of kick-ass women.”

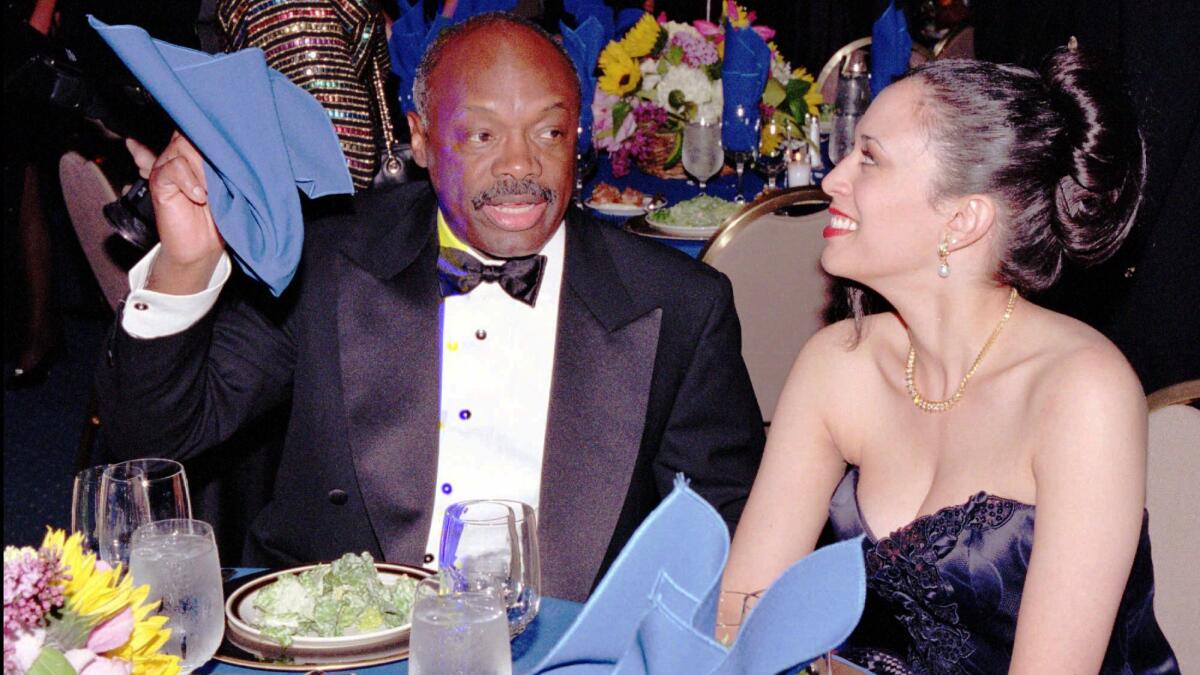

San Franciscans first became acquainted with the name Kamala Harris in 1995, when the late columnist Herb Caen noted her romance with the masterful politician Willie Brown, a considerably older man who had been California’s Assembly speaker and would soon become San Francisco’s mayor. The personal is political: Brown had appointed Harris to a pair of compensated part-time state commissions. The cynical perception pegged her as another piece on Brown’s chess board. Caen approvingly described Harris as San Francisco’s “first-lady-in-waiting.” But several months later, Caen also reported on their breakup.

Across the bay, Harris earned a reputation as a skillful, hard-working prosecutor within the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office. After Howard University and Hastings College of Law, Harris surprised acquaintances who assumed that her liberal sensibilities would lead to a career as, say, a public defender or public interest lawyer. But for Harris, this was all the more reason to be a prosecutor: “It is important for people like me who have a certain perspective and experience to be at the table when important decisions are being made. Why be on the outside begging [when you can be] on the inside where the decisions are being made?”

No other experience as a prosecutor, she says, affected her as profoundly as a series of difficult cases involving the sexual abuse of children. The victims of crime, Harris says, “come from the same community as the defendants,” and tend to be “women, children, the elderly, immigrants. I want to make sure their voices are heard.”

In Alameda County, Harris became a protege of the late Dick Iglehart, an influential career prosecutor. In 1996, after taking a top management role with Hallinan in San Francisco, Iglehart recruited Harris and placed her in charge of the unit focusing on career criminals. Two years later, after Iglehart’s appointment to the bench and amid dissension over his successor, Harris accepted a job in the San Francisco city attorney’s office. Placed in charge of its Children and Family Services Division, Harris turned her attention to teenage prostitution, co-founding a group called the Coalition to End the Exploitation of Kids. Whereas police focused on the crime of selling sex, Harris saw young girls as victims driven by economic necessity, drug addiction and domineering men.

She felt there was an obvious need: Girls who wanted out of the sex trade had no place to turn. San Francisco lacked a “safe house” similar to Hollywood’s Children of the Night. In January, thanks to Harris and her allies, San Francisco will open its first such refuge.

Harris was multi-tasking, building a political base. Lateefah Simon, the 27-year-old director of the Center for Young Women’s Development, which serves residents of the Bayview district, remembers when Harris confided her plans to run for district attorney: “I thought, ‘Please don’t do it.’ ” Critics derided Hallinan as a soft-on-crime liberal, but residents had another opinion. “You think of that office as something that is oppressive to young people, to poor people,” Simon explains. Only later did Simon realize that the district attorney’s job wouldn’t change Harris, but Harris could change the job. “When I sit in a meeting with Kamala, I know something is going to get done.”

“Let’s think outside of the box,” Harris says. “Let’s do some daydreaming, fantasizing about what we want Log Cabin Ranch to look like.”

She is at the head of a long table in her brightly lighted, sparsely decorated conference room, flanked by Tim Silard, an assistant district attorney who focuses on public policy, grants and juvenile justice, and Barry Krisberg, a bearded researcher who wants to radically change juvenile justice in California. Krisberg, president of the Oakland-based National Council on Crime and Delinquency, is credited with helping expose the abuses that are forcing court-ordered reforms at the California Youth Authority. It is the rare district attorney, Krisberg says later, who wants to tackle the shortcomings of juvenile justice. “Most feel they have a narrow role.”

Log Cabin Ranch is a modest county-owned facility for moderate to mid-level male juvenile offenders located on rural land south of the Bay Area, but Harris envisions its reincarnation as a sentencing alternative that would keep San Francisco’s adolescents from the clutches of the California Youth Authority and make the dream of rehabilitation a reality. In this brainstorming session, Harris and Krisberg talk about how, instead of warehousing wayward youths, society needs to provide counseling, education, vocational training and intensive follow-up sessions. They agree on the importance of family counseling.

“You don’t fix kids by dumping them back into dysfunctional families,” Krisberg says. Before the hour is over, Silard has compiled a list of organizations, foundations, labor unions and civic leaders to enlist in the process. “I want to save these kids from the CYA,” Harris says. “And save them, period.”

This, Harris says later, is what she means by “smart on crime.” “Looking at it from a macro perspective, we should always be thinking about crime prevention,” Harris says. “In terms of cost and benefits, and in terms of the psychic costs and benefits, it’s far less expensive to get the services to juveniles than to house them as adults in state prison for years.” Stronger community-based mental health services, Harris says, could help interrupt the pathology that turns young children who have been traumatized and conditioned by violent crime into teenage offenders.

Harris takes a hard line on some crimes, ordering prosecutors to strictly enforce gun violations. The death penalty won’t deter violent crime, Harris reasons, but enforcing gun laws can.

Harris has been accused of a lax attitude regarding allegations of sex for sale in “encounter booths” at exotic dance clubs. Rather than press charges against accused dancers, club operators and the clientele, Harris has called on building inspectors to ensure that the size of booth doors meets codes designed to mitigate the possibility of assault or prostitution. To those who suggest that she is protecting prostitutes, Harris says that safety and preventing violence are her primary concerns.

But there’s no ambiguity in Harris’ attitude toward the prostitution of minors. In August, her office made local history by winning a conviction against a 21-year-old man who was sentenced to three years in state prison for pimping a 14-year-old girl. For the first time in San Francisco, a press release crowed, the pimp was charged with statutory rape and child molestation. “Today we have removed a predator from our streets,” Harris declared.

The earliest polls in the district attorney’s race last year had her in single digits, far behind Hallinan and Bill Fazio, a former prosecutor whom Hallinan had edged out in two previous elections. “I knew we had a chance when we got to 12%,” Harris says. She campaigned constantly, building grass-roots support that reached from women’s groups to law enforcement to some of Delancey Street’s ex-cons who worked alongside her mother at the campaign headquarters. As polls showed Harris coming on strong, Fazio took aim at her obvious vulnerability--her ties to Willie Brown, whose roguish popularity had all but vanished.

A target group of 35,000 professional women received a mailer that featured the image of a woman saying, “I don’t care if Willie Brown is Kamala Harris’ ex-boyfriend” and then went on to criticize Harris for accepting “two appointments from Willie Brown to high-paying, part-time state boards . . . while being paid $100,000 per year as a full-time county employee.”

To Harris, the mailer was “a backdoor attempt” to rub in her association with Brown. Using an automated phone system called Robocall, Harris responded with two-minute recorded messages to the same demographic group, explaining how on the unemployment commission she wrote legal opinions to help assure the extension of benefits to gay couples, and on the MediCal commission she helped keep a Mission District hospital from shutting its doors. Most voters hang up on Robocall, campaign manager Jim Stearns says, but 97% of Harris’ messages were played to the end. The attack backfired, and Harris beat Fazio by 3% to force Hallinan into a runoff, which she won with 56% of the vote, a tally that also exceeded that of newly elected Mayor Gavin Newsom.

“Is that going to be part of the story?” Harris says when asked about her old romance with Brown. She prefers not to discuss her personal life, past or present. Brown, who is rarely reticent, did not return several phone calls. Lateefah Simon says: “Kamala’s in love with her work.”

Politicians who work hard and succeed in San Francisco--such as Feinstein, Brown, Pelosi and outgoing Senate President Pro Tem John Burton--have a knack for ascending to more prominent leadership roles. DeLeon, the political scientist, explains this in Darwinian terms: “So many San Francisco politicians rise because the city is so diverse and the politics are so ruthless. To survive, you have to be extremely skilled.”

On the other hand, the Bay Area is a political bubble. Most Californians, surveys show, remain solidly in favor of the death penalty, so Harris’ opposition may ensure that her political future remains in that insular environment. Arthur Bruzzone, a San Francisco Republican who once hosted a local political TV talk show, argues that San Francisco has now tilted too far to the left to be a good launching pad. Time will tell whether Newsom’s stand on gay marriage or Harris’ “smart-on-crime” crusade will help them statewide, or beyond California. “What’s political poison in one decade can be political dynamite the next,” Stearns says.

Harris is too smart to discuss ambitions beyond her present occupation. But in her inaugural address, she spoke at length of her admiration for a San Francisco politician who had become district attorney 60 years earlier. She described how Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, best remembered as California’s governor from 1959 to 1967, transformed a weak district attorney’s office into a strong one and how he protected the rights of minorities and organized labor before being elected state attorney general. Pat Brown, she also noted, had been inspired by the example of Earl Warren, who had been Alameda County’s district attorney before becoming California’s attorney general, governor and finally chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court during the historic Brown vs. Board of Education ruling.

If an appreciation for history translates into a sense of destiny, Harris won’t say it. A show of pride would be bad karma. Whatever the future holds, the track record suggests that Kamala Harris will be multi-tasking, bringing her own sense of right and wrong to the criminal justice system. “There’s a lot of work that needs to be done,” she says. “A lot of work.”

Scott Duke Harris last wrote for the magazine about MoveOn.org.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.