Column: Gov. Gavin Newsom embraces an untested idea on how California’s rainy-day fund should work

- Share via

Four years after California voters embraced an effort to strengthen state government rules for cash reserves, a new kind of conventional wisdom is taking root in Sacramento about how that system works.

Not all dollars, it turns out, may be equal.

Proposition 2, championed by Democratic legislators and former Gov. Jerry Brown, offered a relatively straightforward approach. It requires a fixed percentage of tax revenues to be set aside in the state’s “rainy-day” fund — some for future use and some to pay off debt. Once the cash reserve grows to an amount equal to 10% of general fund revenues, it’s considered full and the set-aside dollars flow to infrastructure needs.

At the outset, no one thought the Proposition 2 fund would be topped off in the near future, given the percentage of total revenue to be set aside is pretty small.

But things changed when Brown — who watched multibillion-dollar tax revenue windfalls materialize — began urging lawmakers to make extra payments to the rainy-day fund to fill it up sooner rather than later, and as a result the state last year socked away an extra $3.5 billion, which will bring the reserve fund to $15.3 billion by next summer and very close to the 10% threshold.

Newsom unveils a $209-billion budget to boost schools and healthcare and fight poverty »

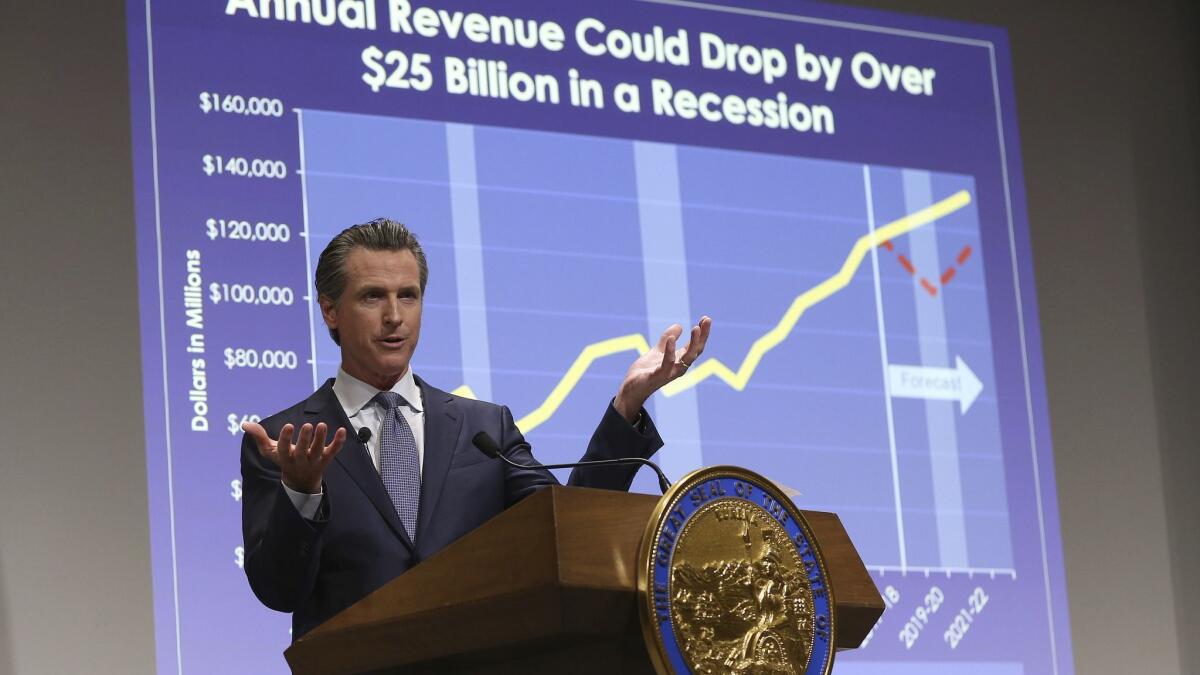

Then, in his budget proposal last week, new Gov. Gavin Newsom asked lawmakers to set in motion plans to add even more to the fund — a total of $4.1 billion more over the next four years.

To those who would suggest that that’s more than Proposition 2 says the account can hold, Newsom pointed to a legal opinion — little talked about until now — that argues there are no real rules governing extra or “voluntary transfers” of tax revenue.

That would mean not only no rules on how much extra money can be put in, but no rules on how it must be spent.

The legal opinion in question was written by the Legislature’s attorneys last September.

“We think a court would conclude that the voters did not intend to restrict the Legislature’s authority to voluntarily transfer funds [to the rainy-day account], to limit the amount of voluntary transfers, or to limit the appropriation of those funds, because there is no express language to that effect,” it said.

In effect, the legal opinion charts a future where the rainy-day fund is essentially divided into two parts: money that’s required to be there and hard to spend, and money that was put into the account just to be prudent and can be spent any time lawmakers see fit. Newsom’s own budget ledger already has two entries for the reserve fund: one showing total deposits and a subset of those that are mandatory.

Having more flexibility isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Last year, the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office cautioned lawmakers about the unintended consequences of shoving money into the rainy-day fund too quickly. They suggested that valuable, one-time needs might go wanting even when cash was plenty under the arcane rules of Proposition 2 that govern what happens when the fund is full.

Critics of the legislative process might argue that continuing to add to the “voluntary” part of the reserve fund means the money can be raided any time that a majority of lawmakers — and in Sacramento, that means Democrats — want to. That may be technically true but could prove politically difficult.

Newsom insisted last week that he’s aiming for budget “resiliency,” not new ways to simply increase spending. Voters will be watching to see whether the new, untested approach to the rainy-day reserve fund meets that test.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.