How ‘MASH’ actor Mike Farrell became a leading voice against the death penalty in California

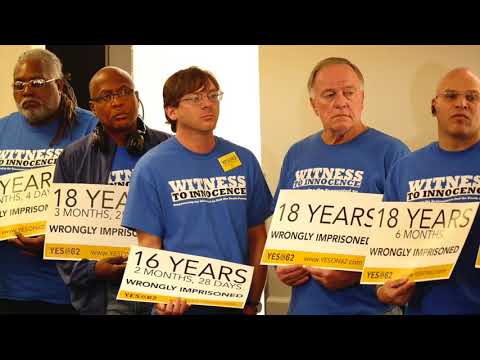

Mike Farrell speaks in support of Proposition 62.

- Share via

The day in 1979 that Tennessee Rev. Joe Ingle landed in Los Angeles and made his way to the set of the popular television series “MASH,” he wasn’t starstruck. He was angry.

As he drove his rental car through the Santa Monica Mountains to the sprawling 20th Century Fox Ranch near Malibu Canyon, Ingle thought of John Spenkelink, a death row inmate. After years of talks with politicians, countless legal filings and many sleepless nights, the state of Florida put his close friend to death in the electric chair, Ingle said.

“We had 220 people on death row in Florida at the time, and many of them had no lawyers,” the United Church of Christ minister said. “We were up against a state machinery of killing that was engaging in full gear, and we could see what was coming.”

Ingle said he thought “MASH” actor Mike Farrell, who had risen to fame as the warm and charismatic Capt. B.J. Hunnicutt, could help the anti-death penalty cause given his stated opposition to executions in a magazine interview. Farrell ended up doing more than that.

Over the past four decades, Farrell, who has wielded his celebrity to bring attention to social and political issues in Central America, the Middle East and Africa, has become a leading voice against the death penalty. This year, he is the author of a ballot measure that seeks to end capital punishment in California. For Farrell, the cause has taken precedence over others because at its root, he says, is the idea that some people are dispensable.

“We have determined that some human beings are not human, are not worthwhile or capable, and that we can just do away with them,” he said. “If you set up that belief system in a society, you can justify torture, assassinations by drone, just about anything.”

The death penalty has been in place continuously in California for almost 40 years, though executions were suspended in 2006 after the current method for lethal injection was challenged in court.

A federal judge in July 2014 ruled the system unconstitutional, finding it arbitrary and ridden with delay. But the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned that decision in November.

Now more than 740 inmates are awaiting execution, almost double the amount in Florida, the state with the second highest death row population in the country. More than 400 do not have lawyers, while the average death penalty appeal takes 25 years or more to go through the process.

But on the Nov. 8 ballot, voters will weigh two competing measures that aim to address what some people on both sides of the issue agree is a broken system. Although both initiatives would require death row inmates to work and pay restitution to victims, Proposition 62, which Farrell sponsored, would abolish the death penalty and replace it with a life sentence without parole.

It has fierce opponents.

Marc Klaas, whose daughter Polly was kidnapped and killed by a person now on death row and who has debated Farrell on a town hall stage and on the radio, argues the public does not want to do away with a punishment reserved for the most vicious members of society.

“There is this moral, elitist certainty that Mike and others of his ilk wrap themselves in, that they are doing this to save a human’s life,” Klaas said. “It gets to a point that they can work to save the lives of death row inmates, giving no consideration to the victims of these people.”

Now ivory-haired and 77, Farrell gained a following from his time on “MASH,” giving him a platform to support the issues he cares about, he said.

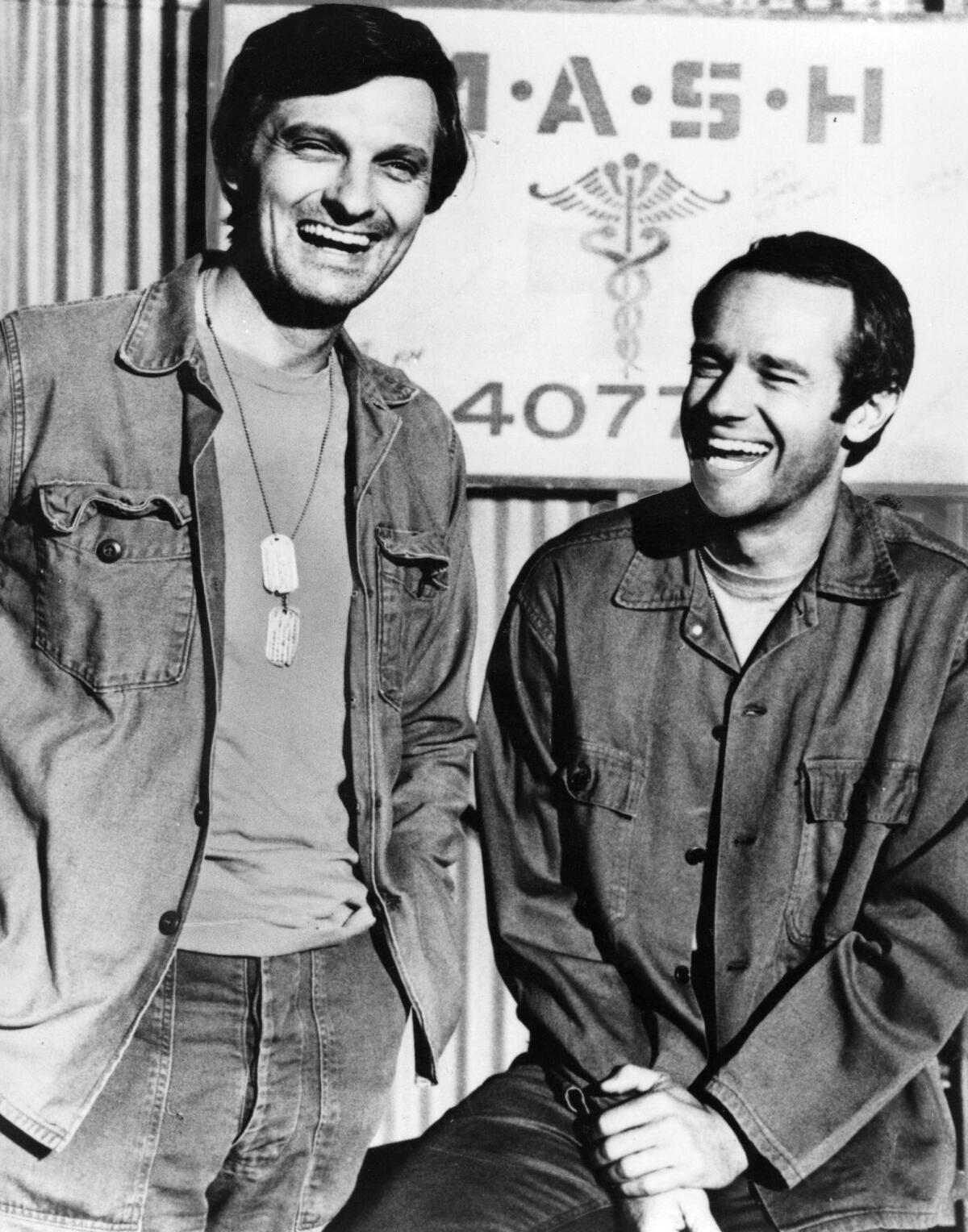

The longest running sitcom in TV history and one of the highest rated, “MASH” beamed into millions of American living rooms for 11 seasons. The show captured the trials of Army doctors working in a mobile hospital under the strenuous conditions of war.

As Hunnicutt, Farrell was the best friend and straight man to funny man Alan Alda, the martini-drinking, laid-back Capt. "Hawkeye" Pierce. Fans all knew B.J. Hunnicutt and that he lived in Mill Valley, Calif.

Farrell was born in Minnesota and grew up in the small, then-unincorporated West Hollywood. He was one of four siblings in an Irish Catholic family, who once delivered groceries to movie stars and had dreams of fame.

As his own star rose, Farrell raised money for union workers and stood up against a 1978 ballot measure that would have banned gay teachers from working in California schools. But his involvement with the death penalty, one of his longest and most passionate causes, dates to the final days of “MASH,” when Ingle paid him a visit.

For years, Ingle had been meeting with death row inmates in southern states and recruiting lawyers to take on their cases. He spoke out against capital punishment, and what he called its arbitrary and racist application on the poor and the poorly defended. With high crime rates and tough-on-crime rhetoric in full steam, his views were unpopular, even dangerous. He received death threats at his home and office, he said.

He took Farrell to see death row at the Tennessee State Prison. Farrell said he did not know what to expect.

“We’d been fed this stuff about people on death row,” he said. “They are deadbeats, they are animals… they are child-eating, fang-toothed monsters.”

What he saw were mostly black and Latino men with little to no education, he said.

“Some of them very, very sorry for what they had done,” Farrell said. “Some of them crazy. Some of them so angry they could hardly speak. And some who said they were innocent.”

A revealing look at California's death row »

Across the country, following mounting legal challenges, legislation and a number of botched executions that have sparked national outcry, at least 20 states no longer have the death penalty.

With 28 executions last year in the United States — the lowest since the four-year, de facto moratorium on the death penalty ended in 1976, when the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed its constitutionality — lawyers and activists say California has become a litmus test for the nation on whether people, not courts or governments, want to continue the practice.

Over three decades, support for the death penalty has dwindled in California, its supporters and opponents said, but not enough to end it. The last time voters weighed a ballot measure similar to Farrell’s current proposition was in 2012, when it was rejected by 52% of voters.

This year, Proposition 66, which was written by death penalty prosecutors, intends to speed up the system. Instead of the California Supreme Court, it would allow the lower court in a case to hear habeas corpus petitions challenging a conviction, and would limit the appeals process to within five years of a death sentence.

A unified campaign to defeat Farrell’s Proposition 62 and bolster the opposing measure has pulled in $4.2 million in donations and garnered wide support from police, sheriffs and prosecutors statewide.

But competing efforts have garnered nearly $6.5 million in donations, and Proposition 62 has attracted some prominent supporters, including billionaire Tom Steyer, hip-hop artist will.i.am and Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Polls have shown mixed results as to which is in the lead.

Farrell said he has witnessed a shift in policy and public opinion against the death penalty “little by little,” as more than 155 men and women nationwide have been exonerated since 1973 — some having come within hours of execution before their convictions were overturned.

As the former president of the nonprofit Death Penalty Focus, founded in 1988, he has raised defense funds for those inmates he believes are innocent, no matter how grim their cases.

Criticisms that the group champions murderers over victims upsets him, Farrell said, as he and fellow activists have lost loved ones to crime. “I don’t think a victim is benefited by someone else being made a victim,” he says.

But their opponents argue that most of their cases, including all of those reversed in California, have been dropped or dismissed on technicalities, such as ineffective counsel or an improper jury instruction.

San Bernardino District Attorney Michael Ramos said he only wishes Farrell could stand in his shoes, when comforting a grieving mother whose daughter has been savagely raped and killed.

“I believe in the death penalty for a very small percentage of individuals,” Ramos said. “He is not in the justice system. He doesn’t see what we do every day.”

Tami Alexander, wife of former NFL player Kermit Alexander, says she respects Farrell. But she wants to see Tiequon Cox executed. More than 30 years after the gunman went to the wrong address and killed her husband’s mother, sister and two nephews, he remains on death row.

“I applaud Mike, I really do,” she said. “I feel he has dedicated his life to a very toxic issue, but he doesn’t have a dog in the fight.”

On a recent Sunday in West Los Angeles, Farrell sat in the front pew of the Holman United Methodist Church, with more than a dozen people from across the country who have formed the Witness to Innocence project.

Alongside Farrell was Nathson Fields, who was acquitted in 2009 in the deaths of two rival Chicago gang members after spending 20 years in prison. And Lawyer Johnson, whose charges were dropped after he spent 10 years in prison for a 1971 slaying in Massachusetts.

And Harold Wilson, whose conviction was overturned in 2005 based on DNA evidence after he served more than 16 years for the slayings of three people in South Philadelphia.

In the church foyer later that morning, Wilson’s voice shook with rage at the thought of prosecutors who still denied his innocence. When he was locked up, he said, his daughter was 3 years old. “I am still suffering,” he said.

Outside, Farrell shook hands with patrons, some of whom remembered him from his “MASH” days and had watched the show with their parents or grandparents. People often question why Hollywood actors meddle in politics and social causes. But Farrell says he sees himself as a concerned citizen, not an activist.

In debates and panels, he says, his critics have often told him death row inmates “‘don’t deserve to live.”

“But the really important question people don’t ask is, ‘Do we deserve to kill?’”

Follow @jazmineulloa on Twitter

ALSO:

California voters oppose ending state's death penalty

Richard Branson, will.i.am endorse California ballot measure to end the death penalty

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.