Before John Cox was Trump’s choice for governor, he was on a quixotic mission to remake California’s Legislature

- Share via

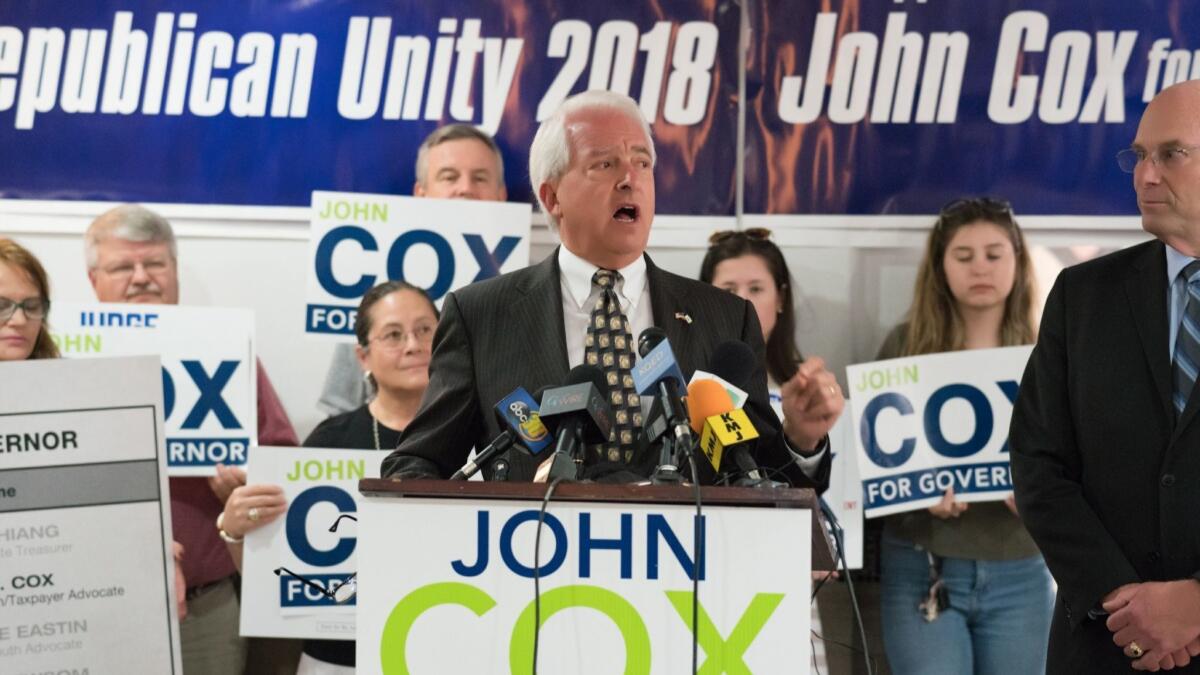

Reporting from Sacramento — John Cox’s campaign to be California’s next governor follows an unsurprising formula for a Republican running in 2018: one part anti-tax warrior and another part Trump-inspired hard-liner on immigration.

But when he started his gubernatorial run in March 2017, he offered a more unorthodox pitch. His campaign launch centered on an idea to revamp the state Legislature and add thousands more local representatives in order to squelch the influence of moneyed interests in politics.

“I have a plan to make legislative districts small enough that anyone can run — and they won’t need special interest money to do it,” Cox said in his announcement video.

In the run-up to the June primary election, Cox’s “neighborhood Legislature” idea has largely disappeared from his stump speech. Nevertheless, the idea is central to his political profile in California.

Since first proposing the plan in 2011 — one of Cox’s first forays into Golden State politics — the Rancho Santa Fe businessman has invested millions of his own money to turn his brainchild into a statewide initiative. He has failed in his multiple efforts to qualify it for the ballot.

This quixotic journey laid the groundwork for Cox’s gubernatorial bid — which, like the initiative campaigns, depends heavily on his personal wealth. And for a candidate with a scant resume in public service, the initiative offers the best look into Cox’s approach to politics, at once idealistic and unyielding to change.

Cox’s campaign declined to make him available for an interview for this article.

The idea hasn’t changed much since Cox first floated it seven years ago, not long after he moved from Illinois to the San Diego area.

The state would be carved into 40 Senate districts and 80 Assembly districts — as it is now — and then further divided into “neighborhood districts” of about 5,000 people per Assembly member, or 10,000 people for every senator. Assembly districts currently comprise about 450,000 residents and Senate districts contain just under a million people.

The nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office estimated Cox’s plan would result in about 3,900 state senators and 7,800 Assembly members. The neighborhood representatives in a district would then elect one senator and one Assembly member to serve in each chamber’s “working committee” — a group of 40 senators and 80 Assembly members, equal to the number in the current system, would hold committee hearings and craft bills. But nearly all legislation, including budget bills, would have to be approved by the full, nearly 12,000-member Legislature.

By dramatically reducing the size of districts, Cox has said it would make running for office cheaper, reducing the need to raise lots of money.

“Legislators are largely responsive not to the voters, but to the funders and the lobbyists whose bills they are going to vote on,” Cox said in his 2017 video. “You couldn’t have designed a system more fraught with temptation or ripe for reform.

“These smaller, neighborhood districts will allow elections to be decided on issues and character — not 30-second commercials or vicious mail pieces,” he continued.

Cox has also pitched his plan as a money saver. Legislators get paid more than $100,000 annually, plus per diem costs for travel and lodging while in Sacramento. Under the most recent iteration of the proposal, the neighborhood lawmakers would make $1 per year, while working committee members would be compensated at 120% of the median state income.

The plan also included a spending cap, limited to two-thirds of the prior year’s spending. In all, the legislative analyst estimated state spending would decrease by $100 million annually, but increased county costs could total in the tens of millions each election year.

Tim Rosales, Cox’s campaign manager and a consultant on the most recent attempt to qualify the initiative, said the proposal underscores Cox’s broader view of government.

“It reiterates everything he’s been about his whole career: government reform,” Rosales said. “He believes, and I think a lot of people believe, the system isn’t working.”

Cox’s proposal first failed to qualify for the ballot in 2012. Undeterred, he made another attempt the next year. The second time, he participated in a handful of symposia across the state focused on government reform efforts to increase voter participation and tackle the influence of money in politics. Other participants recalled Cox as an enthusiastic and forceful salesperson for his outside-the-box plan.

“At face value, the idea of dramatically increasing the number of politicians in California is going to be met with a lot of skepticism. Over the course of the program, John was able to explain to the audience why it was a potentially plausible solution,” said Dan Schnur, a former Republican consultant, now registered with no party preference, who teaches at USC and UC Berkeley. “He convinced some people, he didn’t convince others. But very few people left thinking it was a ridiculous idea.”

Among government reform enthusiasts, Cox’s sales pitch could be well-received — or at least not dismissed out of hand. But the proposal’s complexity made it a hard sell to most California residents.

“Anyone who hears the sound-bite automatically assumes the Legislature will have to meet in the Rose Bowl,” Schnur said. “It takes a while to explain that is not what this is about.”

Kathay Feng, executive director of California Common Cause, an advocacy group that participated in the 2013 meetings, said she could see the appeal in creating a system that brings constituents closer to their elected officials. But she said her group had questions about how the proposal would be implemented.

“Our biggest challenge in thinking about this was the logistical one — how one convenes something that has several thousand people, and how you have manageable decision-making on things that require some level of homework and expertise,” Feng said. “It wasn’t clear to us that it had been fully fleshed out.”

Common Cause did not take a position on Cox’s idea.

“He had really made up his mind about the proposal. He had moved beyond an editing mode,” Feng said. “Our feedback was received very politely, but without much impact.”

Trump endorses Republican John Cox for California governor »

Cox’s campaigns for the neighborhood Legislature proposal picked up a handful of other donors, but the engine was predominantly his personal wealth, accumulated from his work in venture capital and real estate management. Between 2013 and 2017, he gave or loaned nearly $3 million to committees backing the initiative.

The investment has yet to land the idea a spot on the ballot. Cox has tried and failed to qualify the initiative five times, most recently coming up short this February.

Another unconventional plan by Cox — a ballot initiative to require lawmakers to wear emblems of their biggest donors on their clothes, much like NASCAR drivers displaying their sponsors — also has not gotten far. Cox has dedicated nearly $400,000 to that effort, but has not qualified the initiative to put it before voters.

Cox’s eager spending on his initiatives set the template for his current gubernatorial run. He has poured more than $4.9 million into his campaign to be California’s chief executive, accounting for around 75% of his total fundraising haul.

And if Cox is successful in becoming the next governor, Rosales said Californians should expect more talk of government reform to follow — but stopped short of saying the neighborhood Legislature would be at the top of his agenda.

“Whether or not there was merit to the idea, there is merit to the idea that reform was needed in some way,” Rosales said. “Even if this isn’t the right idea or the idea that everybody necessarily rallies around, it gets the discussion going.”

Follow @melmason on Twitter for the latest on California politics.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.