With one final signature, Gov. Jerry Brown closes the chapter on his quest to reshape California’s budget

- Share via

From the first time decades ago he was lampooned as a quirky upstart until now, the final stretch of his unprecedented fourth term as California’s governor, Jerry Brown has reveled in his reputation as a cheapskate.

“Nobody is tougher with a buck than I am,” he boasted during the 2010 campaign that sent him back to Sacramento.

Eight years later, Brown is poised to earn a place in the history books as the leader who helped right the ship of state. His mantra of measured spending could be a standard by which future governors are judged.

“We’re well positioned, but if the next governor doesn’t say ‘no’ at critical moments, things will get worse,” Brown said in an interview with The Times.

His promise of similar straight talk about California’s budget prevailed in the 2010 election, held in the shadow of financial collapse. The projected budget deficit he inherited — even after two years of cuts under Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger — stood at $27 billion.

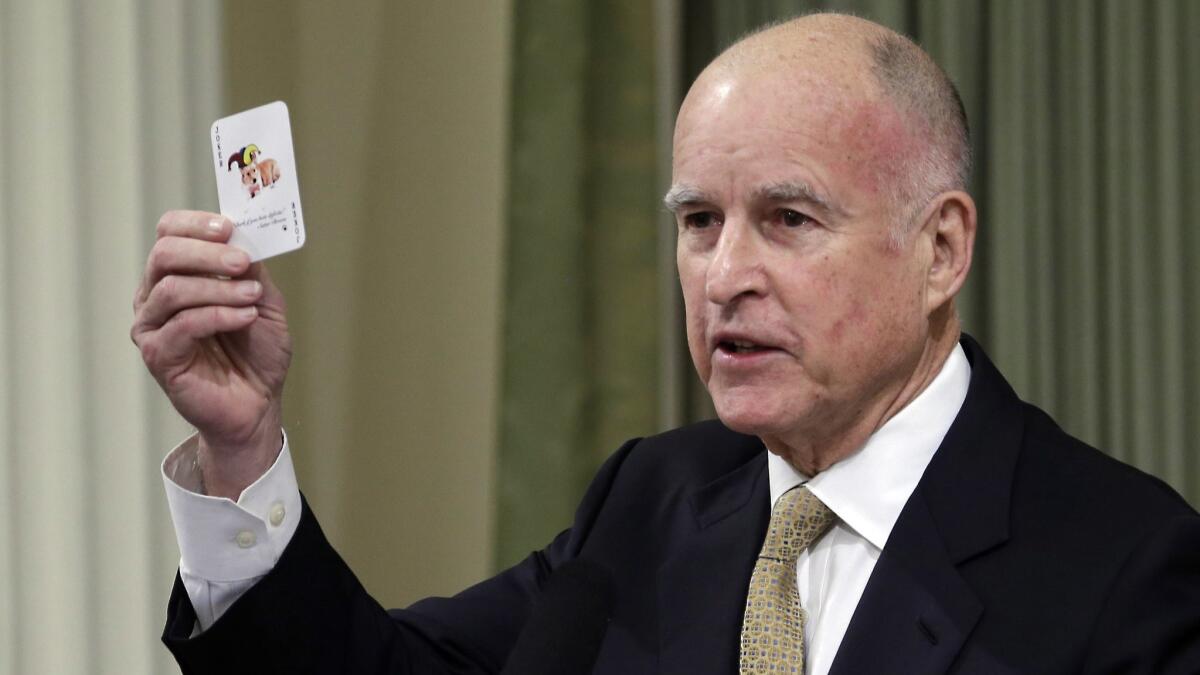

All of which seemed a distant memory Wednesday as Brown signed a budget creating a $13.8-billion cash reserve, the largest in state history. “I think people in California can be proud that we’re making progress,” the 80-year old Democrat said standing beside legislative leaders — the oldest of whom was only 12 when Brown was first elected governor in 1974.

While supporters tout his record on combating climate change or raising the minimum wage, the through line of Brown’s second chance as governor has always been the budget, a topic that demanded a fiscal reckoning just days after he took office.

“What surprised me was how deep the deficit became during Schwarzenegger’s last few years,” he said. “We had to get in there and cut, and find some new revenue and work it out the best way we could.”

Brown’s first moves in 2011 were to cancel new cell phones and government vehicles for state workers, political symbolism not unlike the bland Plymouth sedan he chose in the 1970s from the state vehicle pool. By spring, he convinced lawmakers to cut $8.2 billion from programs like higher education, daytime elderly care services and doctor visits for the poor.

When substantive efforts to solve the rest of the problem stalled that June, the governor did something his predecessors had never done: He vetoed the budget ratified by lawmakers.

“For a decade, the can has been kicked down the road and debt has piled up,” Brown said as he signed the veto message. “California is facing a fiscal crisis, and very strong medicine must be taken.”

The veto was a shot across the bow to the Legislature. “It communicated very clearly that there was going to be a minimum standard for the legislative budget, and they just couldn’t slap anything together and put the name ‘budget’ on it,” Brown says now.

“We were frustrated,” remembers John A. Pérez, who was Assembly speaker at the time. “But it laid the foundation for what has become eight years of on-time, balanced budgets.”

Deeper cuts ultimately were made. Within months, ratings agencies moved California’s credit outlook to positive, the beginning of a trend that has driven down interest rates for government borrowing, one way the state has saved money.

Gov. Jerry Brown’s wall of debt crumbles, but more walls are behind it »

He later turned his attention to the short-term obligations that piled up during the financial crisis, from raided school funds to Wall Street-backed deficit bonds. Branded by Brown as the state’s “wall of debt” and once towering at nearly $35 billion, today the balance is less than $5 billion.

“I tell my friends that Jerry Brown is one of the most fiscally conservative Democrats that I know,” said Connie Conway, a Tulare County Republican who served as Assembly GOP leader from 2010 to 2014. She recalls saying at one point that Brown “is the adult in the room because at least he’s admitting we have debt.”

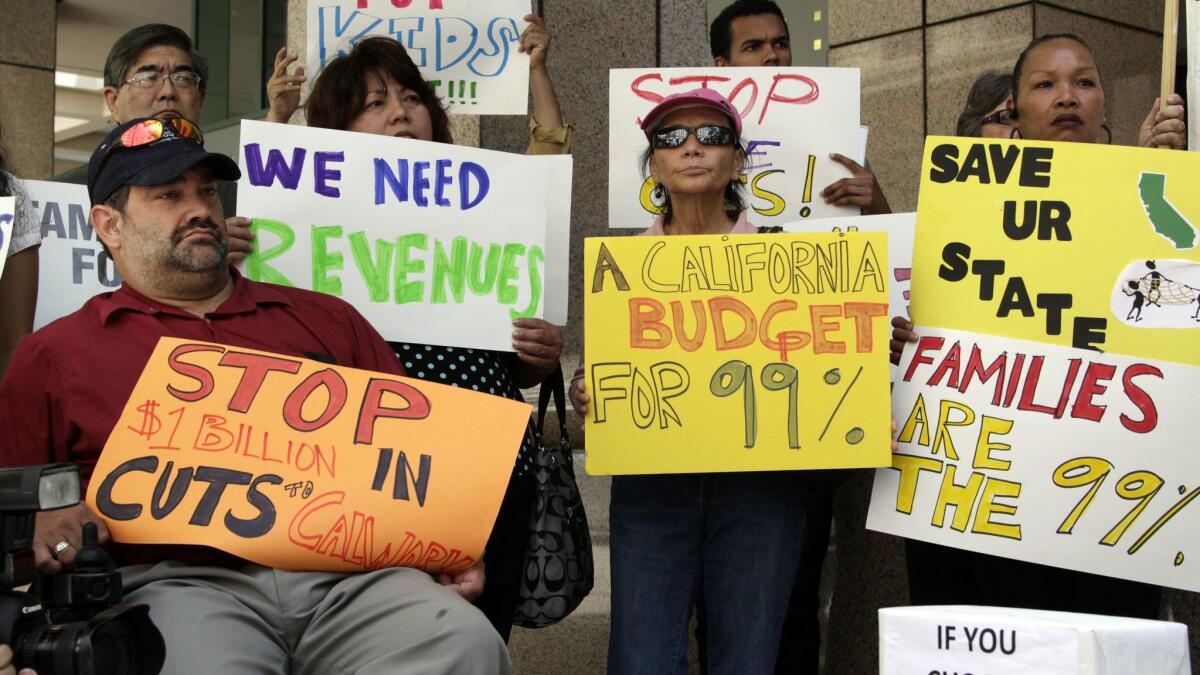

Still, it was Republicans who handed Brown his first real budget setback in 2011, refusing to support a special statewide election to extend temporary taxes. The governor, never a back-slapping kind of politician, nonetheless mounted an intense charm offensive. He hosted private dinners for legislative Republicans where California wine flowed freely. He brought along his affable Corgi, Sutter, for visits. GOP lawmakers wouldn’t budge.

In hindsight, it was a lucky break. Special elections have historically had a disproportionately high turnout of conservative voters who likely would have rejected the plan. When Republicans balked, Brown and a coalition of business and labor leaders qualified a tax increase for the ballot in 2012, a presidential election year with strong turnout from Democrats.

The resulting Proposition 30, a surcharge on the state’s sales tax and the incomes of wealthy taxpayers, provided revenue for six years — a more robust plan, Brown now says, than what he asked Republicans to support. “We’d have been right back in the soup” with the original plan, he said. “This way, we got a couple of more years.”

Brown campaigned hard for the ballot measure, shrewdly making it about the budget’s biggest beneficiary — schools — and about his own commitment to balancing the books. On election day, it passed with 55% of the vote.

“There’s no way in hell the voters would have approved those taxes if not for their faith in his fiscal stewardship,” Pérez said.

The taxes and California’s recovering economy have since produced historic tax windfalls. The state Department of Finance estimates the 2012 tax initiative and an extension approved by voters (but not explicitly endorsed by the governor) in 2016 has, to date, generated $50 billion in additional revenue.

Brown’s budget dominance begins with a firm grip on tax revenue forecasts »

Not that all of the modern Brown era has been all about less spending. State government spending has risen by 59% since 2011. Much of that has gone to K-12 schools, as required by law, and Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program. Healthcare spending, in particular, has more than doubled in seven years, to about $23 billion in general fund costs. California has fully embraced Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Brown has lashed out at efforts by President Trump to rescind the law.

The rush of revenue also has allowed for a substantial savings account. Brown and lawmakers crafted a robust rainy-day reserve fund, ratified by voters in 2014. “That’s the kind of collaboration you don’t often see between legislators and governors,” Pérez said.

Through lean and flush years alike, the governor’s job approval ratings remained strong. Liberal activists routinely criticized him for not doing more to help those in need, suggesting with an increasing frequency through the years that the scion of a prominent political family had never experienced those struggles first-hand.

“They’re always asking for more,” he said. “There’s no natural limit. There’s no predator for this species of budgetary activity, except the governor.”

Even critics acknowledged that Brown kept listening to advocacy groups. In 2016, he agreed to remove a provision in the state’s welfare assistance program, CalWORKs, that denied coverage to children born while their families were already receiving benefits. The ban had been in place for almost two decades.

“We came a long way,” said state Sen. Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles), the chair of the Senate’s budget committee and a vocal advocate for changing the welfare rule. From the beginning, she said, Brown’s advisers said it was about the cost, not the policy.

This year, Mitchell convinced him to go even further — a small increase in the size of CalWORKs’ monthly cash grants, subsidies that failed to rise with inflation for more than a decade.

Mitchell recalled a flight from Los Angeles during which Brown, a voracious reader, spoke at length about a book that chronicled poverty around the world. “And I was able to say to him, ‘Yes, that chapter right there, that sounds like Central California,’ ” she said.

Likening income inequality to his celebrated efforts on climate change, Mitchell said she once told Brown, “By you just making it a priority, you’ve had worldwide impact. So have the same attitude about poverty.”

In recent years, Brown has agreed to expand childcare programs, Medi-Cal coverage for children regardless of immigration status and a state earned income tax credit for the working poor.

“His track record on issues of poverty, inequality and economic security adds up far better [over two terms] than it often looked in individual budget years,” said Chris Hoene, executive director of the nonprofit California Budget and Policy Center, which advocates for the working poor.

Looking beyond the one-year-at-a-time approach to state budgets may be an important legacy of the Brown administration. The governor pointed to recently adopted five-year plans as a way to get a better look at what’s over the horizon. “It gets people thinking about the inevitable consequences of the decisions in this budget,” he said.

It also may help break one of the more ignominious traditions of California governors: leaving a fiscal mess for the next person to clean up. It’s the kind of dilemma his father, the late Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, left Ronald Reagan in 1967 and he left the late George Deukmejian in 1983.

“The story is one of governors always hitting a wall and leaving a big, fat deficit,” he said. “I wanted to avoid that if I could.”

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.