Newsom signs ‘Stephon Clark’s Law,’ setting new rules on police use of force

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — After an emotional fight that laid bare the chasm between California’s communities of color and police, Gov. Gavin Newsom on Monday signed Assembly Bill 392, creating what some have described as one of the toughest standards in the nation for when law enforcement officers can kill.

Intense private negotiations and public outcry influenced the final language of the legislation, which will take effect on Jan. 1. Recent fatal police shootings of unarmed black men, in particular, prompted activists to seek changes in rules that in some cases were more than a century old. Though the final bill doesn’t go as far as some wanted, supporters say it’s a first step in changing the culture of policing in California.

“The bill is watered down, everybody knows that,” said Stevante Clark, brother of Stephon Clark, who was shot by Sacramento police in March 2018. “But at least we are getting something done. At least we are having the conversation now.”

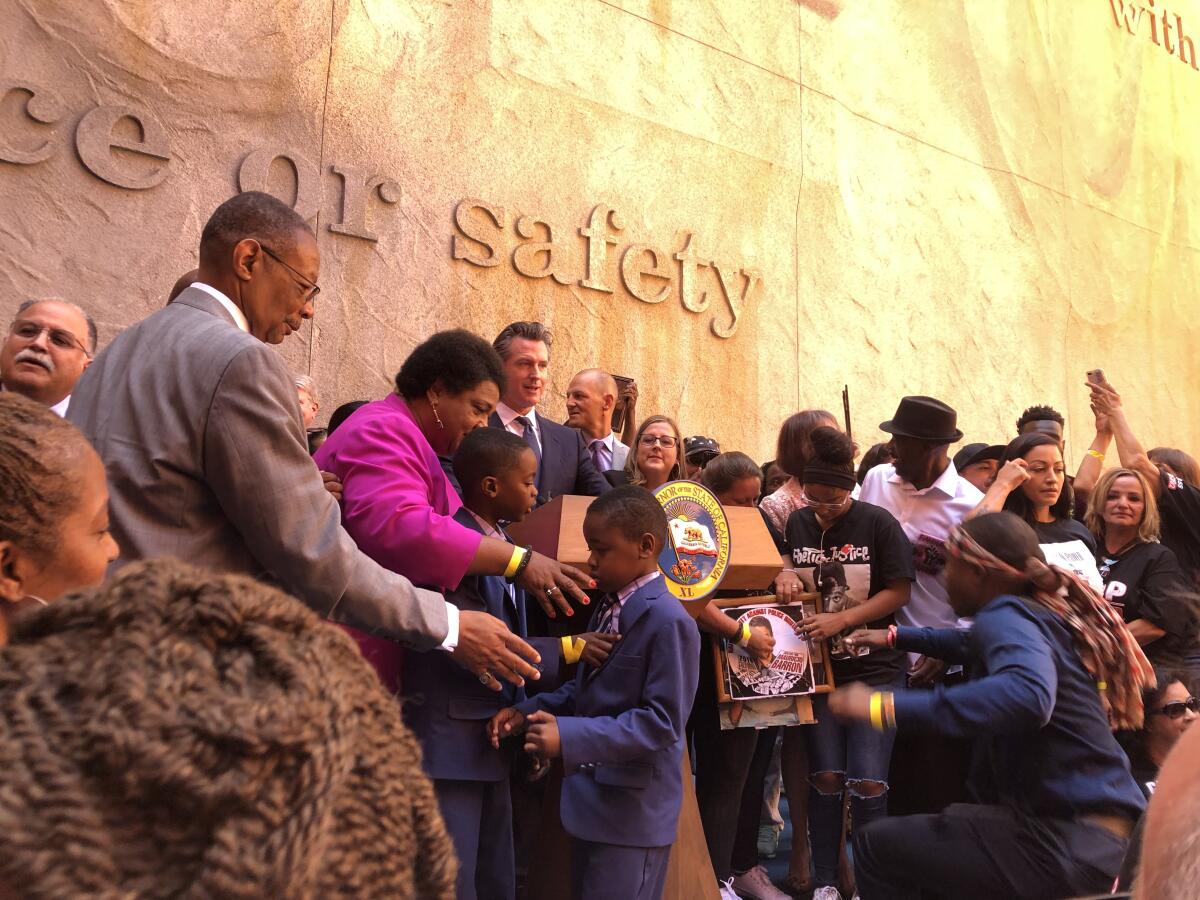

Newsom invited dozens of family members who had lost loved ones to police violence to join him onstage as he signed the bill in Sacramento at a large event at the secretary of state’s courtyard. He acknowledged the bill’s intent to change police culture would be determined by how it’s implemented.

“This is remarkable to get to this moment on a bill that was so controversial, but it means nothing unless we make this moment meaningful,” Newsom said afterward. “And so that is the goal and the desire of all of us, law enforcement and members of the community, to address these issues in a more systemic way, and that’s going to take a lot more work than passing a piece of legislation.”

Assemblywoman Shirley Weber (D-San Diego), the law’s author, said the new law could be a model for other states.

“This will make a difference not only in California, but we know it will make a difference around the world,” she said.

What does the law do?

The new language will require that law enforcement use deadly force only when “necessary,” instead of the current wording of when it is “reasonable.” In large urban law enforcement departments that already train for deescalation and crisis intervention, day-to-day policing will probably not noticeably change.

The law also prohibits police from firing on fleeing felons who don’t pose an immediate danger, an update from California’s original code that dates back to 1872.

How will it help curb the use of lethal force?

Under current law, prosecutors can only consider the moment lethal force was used when determining if an officer acted within the law. Did an officer reasonably believe his or her life or bystanders’ lives were in danger in those seconds?

Under the new standard, prosecutors can also consider the actions both of officers and of the victim leading up to a deadly encounter, to determine whether the officer acted within the scope of law, policy and training. Opening up those tactics to scrutiny, supporters believe, will encourage departments to train officers in deescalation and other strategies that could decrease the use of lethal force and provide a potential path to accountability when it is used.

Weber, the bill’s author, said recently that AB 392 will be an “aggressive effort to retrain our officers and change the culture of police.”

What does law enforcement think of the change?

Law enforcement groups vehemently opposed AB 392 when it was introduced. They backed a counterproposal, Senate Bill 230, written by state Sen. Anna Caballero (D-Salinas), that largely left current law unchanged but instead focused on training. SB 230 was significantly altered during the committee process and was amended so that it could pass only if AB 392 did.

After months of negotiations, law enforcement groups, including the California State Sheriff’s Assn. and the California Highway Patrol, unexpectedly dropped their opposition to AB 392 after it was amended to address their concerns. Newsom and leaders of both the Assembly and Senate then threw their support behind the measure.

Though law enforcement representatives were largely absent from the signing ceremony, many voiced support Monday for the new law.

“Together, AB 392 and SB 230 will modernize our state’s policies on the use of force, implementing the very best practices gathered from across our nation,” said Ron Lawrence, president of the California Police Chiefs Assn. in a statement.

What exactly changed to end law enforcement’s opposition?

Language requiring deescalation and a definition of what “necessary” force means were removed, along with passages about potential “criminal negligence” of officers involved in lethal incidents.

Law enforcement lobbyists also faced a new political regime at the state Capitol. For years, bills opposed by law enforcement had little chance of advancing, and law enforcement lobbyists held almost insurmountable clout. But Newsom, Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) and Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) broke that tradition by insisting on a compromise measure.

Will more police be prosecuted under this law if they use deadly force?

It’s possible but unlikely to become common. The decision on charging law enforcement personnel involved in deadly force incidents still remains in the hands of local district attorneys, and the underlying standards for when it is legal are still set by federal case law.

AB 392 opens the door for prosecutors to look at more factors when making a charging decision, including events leading up to the deadly encounter. But it doesn’t provide clear language on what “necessary” means. That will be left to prosecutors and courts to decide.

How does this law address issues of race in policing?

Weber introduced the bill during the upheaval following the killing of Clark by Sacramento police. Two officers shot Clark, a black man suspected of breaking car windows, after they mistook his cellphone for a gun. The incident prompted massive protests, which spilled into the Capitol, bringing with them the national debate over the disproportionate number of people of color killed by police.

In 2018, there were 628 instances of use of force that resulted in serious bodily injury or death in California, according to data collected by the state attorney general. Though the overall number represents a decline from previous years, nearly 47% of civilians involved were Latino and 19% were black — statewide, about 40% of residents are Hispanic or Latino, and 6.5% are black.

Nationwide, a recent study found that about 1 in 1,000 black men and boys can expect to die at the hands of law enforcement, and that people of color regardless of gender are killed by police at higher rates than their white counterparts.

Along with Stevante Clark, dozens of families of color whose relatives were killed by police packed committee meetings, offering raw testimony both about the incidents themselves and how communities of color are policed. Racial bias in policing is not directly addressed by AB 392, but implicit-bias training will probably be a part of new training standards.

Supporters argue that more emphasis on nonlethal practices will reduce lethal use-of-force incidents overall. “This is Stephon Clark’s law,” said Stevante Clark. “The cost, the price that had to be paid for this, it hurts. ... I hate that this had to come out of such a tragic situation, but at the same time, it helps the healing process to know his name could possibly prevent something like this from happening again.”

When does it go into effect?

Although the law technically takes effect in January, it will take some time for law enforcement across the state to be retrained in the new standards. The state Commission on Police Officer Standards and Training will have to decide the details of that training before the state’s nearly 80,000 sworn officers receive it.

Ultimately, the scope of the law will have to be hashed out in court — which will require any prosecutions of officers to wind their way through what likely will be years of litigation.

What’s next?

Senate Bill 230, the training bill tied to AB 392 and supported by law enforcement, is stuck in committee in the Assembly in part because backers of AB 392 fear that language added to it weakens the new law and could undermine its intent. Law enforcement lobbyists counter that the language is necessary for clarity. In particular, some community groups object to wording that requires deescalation only when its “feasible.” The fate of that contentious bill remains uncertain.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.