Hackers attacked California DMV voter registration system marred by bugs, glitches

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — California has launched few government projects with higher stakes than its ambitious 2018 program for registering millions of new voters at the Department of Motor Vehicles, an effort with the potential to shape elections for years to come.

Yet six days before the scheduled launch of the DMV’s new “motor voter” system last April, state computer security officials noticed something ominous: The department’s computer network was trying to connect to internet servers in Croatia.

“This is pretty typical of a compromised device phoning home,” a California Department of Technology official wrote in an April 10, 2018, email obtained by The Times. “My Latin is a bit rusty, but I think Croatia translates to Hacker Heaven.”

Although the email described the incident as the DMV system attempting “communication with foreign nations,” a department spokesperson later insisted voter information wasn’t at risk.

The apparent hacking incident was the most glaring of several unexpected problems — never disclosed to the public — in rolling out a project that cost taxpayers close to $15 million.

The Times conducted a four-month review of nearly 1,300 pages of documents and interviewed state employees and other individuals who worked on the project — most of whom declined to be identified for fear of reprisal. Neither the emails nor the interviews made clear who was ultimately responsible for the botched rollout, though an independent audit is expected to be released in the coming days.

The emails present a picture of a project bogged down by personnel clashes, technological hurdles and a persistent belief among those involved that top officials were demanding they make the “motor voter” program operational before the June 5 primary, so that it could boost the number of ballots cast.

“Not meeting the deadline was not an option,” said a project staffer who asked to remain anonymous to speak freely about what happened. Three other team members agreed there was enormous pressure to get part of the program running before the end of April.

Some of the mistakes popped up within hours of the system going live: frozen or blank DMV computer screens; private information remaining on touchscreen devices between appointments; selections sometimes flipping from what a customer had chosen.

Three weeks later, mistaken records showed up at local election offices, upward of 100,000 inaccurate documents by the fall. Party preferences were wrong. Some non-citizens were mistakenly added to the voter rolls. Other DMV customers didn’t know they’d been registered.

Staffers from a trio of state offices were involved — led by Chief Information Officer Amy Tong, Secretary of State Alex Padilla and former DMV Director Jean Shiomoto. But none seemingly had ultimate authority over the beleaguered project. Emails show that advisors to former Gov. Jerry Brown also closely monitored the work.

Some on the team building the system sounded those alarms, but to no avail.

“If we want to avoid an international incident and major security and launch failures on the scale of recent news stories about Facebook, IRS, or the Office of Personnel Management — we need state executives to understand the serious nature of the current high-pressure rush to launch,” a senior programmer wrote in an email the day before the system went live.

Building California’s automated voter registration system wasn’t going to be easy.

Programmers had to create a workaround for the DMV’s outdated computer system that could transmit thousands of daily registrations to state elections officials. Even a small mistake could result in a voter with the wrong ballot, or no ballot at all.

For the DMV, the timing was particularly tough. Its employees were already behind on technology needs to implement the federal Real ID program — a separate task that a recent audit said contributed to long lines at local department offices last summer.

Across all the agencies involved, the pressure was intense. Some programmers worked 30 hours straight without sleep in the final days, taking short naps on conference room floors.

“I wouldn’t argue with anyone who would say give us more time,” said Tong, who is both chief information officer and director of the California Department of Technology. “Of course, I wanted more time.”

Time — or lack of it — was a consistent problem. The CDT was enlisted to join the effort almost 19 months after the original law was signed. Tong said the Brown administration wanted it in place before the June 5 statewide primary. And at a May 2017 meeting, according to an email reviewed by The Times, a momentous decision was made: Move the project’s launch date from July to April.

It was an aggressive decision, programmers involved in the effort and others with extensive knowledge of government information technology said. But any worries expressed weren’t widely shared.

“We were told, yeah, sure, shaving off 90 days, that seems very doable,” said Padilla in an interview. “Nobody raised a significant concern.”

The “new motor voter” program, as it was known to state officials, was born with great promise.

After more than two decades of complaints and a 2017 lawsuit over how California’s DMV handled voter registration, the new system was promised to be a solution. Democrats, too, were happy — seeing it as a way to boost voter turnout across California, likely helping their party’s chances on election day.

The 2015 law required every citizen receiving a new or updated driver’s license be registered to vote unless opting out. Seven million eligible Californians were unregistered to vote at the time of the law’s enactment.

Implementation was slow. A database of all registered California voters, a key requirement and itself a decade overdue, wasn’t completed until the fall of 2016. From there, another eight months passed without substantive discussions on the automated voter registration system.

Wesley Goo, a DMV deputy director, said officials needed final regulations and state budget funding. “Our timeline to implement this project hadn’t really started yet” before the late spring of 2017, he said in an interview.

Tong said engineers struggled with the DMV’s outdated, cumbersome computer system. “You go in and you kind of open up the hood of the car, so to speak, and you’re like, ‘Wow, OK, this is kind of how all of these are cobbled together,’” she said. “And we kind of tried to untangle all of that.”

The partnership wasn’t easy. DMV staffers weren’t prepared, Goo said, for the work plan imposed by the Department of Technology. Several people who worked for Tong, on the other hand, told The Times they found DMV officials reluctant to fully cooperate.

“They had a thousand ways of saying no,” said one former project employee about the DMV, who asked not to be identified in order to speak candidly.

Kane Baccigalupi, at the time a senior CDT programmer, said she spent months repeatedly asking DMV technology staff members for technical information to begin designing the motor voter system.

“I had loud conversations with, like, anyone that would listen because we didn’t have any access to the systems that we needed to integrate with,” she said.

The CDT’s team had its own internal problems. In mid-February, two months before the launch, a top programmer emailed Tong that the project was “spinning out of control,” insisting that a “documented project plan still does not exist” and noting that a highly regarded private contractor, John O’Duinn, had abruptly quit after disagreements about how to prioritize the work. O’Duinn declined to comment on the project.

“The window for success in April is narrowing fast,” the CDT programmer wrote.

In an interview, Tong denied such problems affected the project’s ultimate success. “Those were raised and we mitigated and had a very open dialogue about it,” she said.

Still, documents and interviews reveal clashes that consumed valuable time needed to build the computer system, including additional testing before introducing it to the public.

As the launch drew near, various technical glitches appeared — some difficult to diagnose and fix in the push to launch the system early.

A project timeline written in late 2017 shows that three months for testing key elements were condensed to six weeks. In other areas, design and testing would have to be done simultaneously.

In late February, the secretary of State’s chief counsel said he was concerned that a key component — how voter data would be transmitted from the DMV — was still incomplete. “There are a number of cascading issues on our end that are quickly mounting that we need to get a handle on,” wrote Steven Reyes.

Emails frequently cited concern about the lack of time for testing.

“I hope everyone appreciates that proper testing remains a significant long-term project risk,” an outside consultant, Michael Wiederhold, wrote in an April 7, 2018, email. “Consider, for a moment, the pressures we will face supporting these systems after go-live should something go wrong in production.”

Three days later, a portion of the voter registration system tried to contact computers in Croatia.

“Much of the traffic is highly suspicious,” a state official, Marc Hanson, wrote in an email a few hours after the incident.

Others had expressed concerns about whether the system being built was fully secure. One engineer, who declined to be identified, said the incident was aided by the “back door” of the voter system being left “unlocked.”

CDT officials said the incident was not the reason for the program launching one week later than originally expected.

Carlos Ramos, California’s technology director from 2011 to 2016, said a hacking attempt on a major project should always merit more than a quick check. “I would dig into that and find out what’s going on,” Ramos said.

Tong downplayed its significance in an interview with The Times. “We were constantly monitoring, and this was brought to everybody’s attention,” she said. “And it was addressed immediately.”

If the project dodged a bullet with what staff members called “the Croatia incident,” other serious problems appeared in the hours leading up to — and the actual day of — the new motor voter system’s April 23 launch.

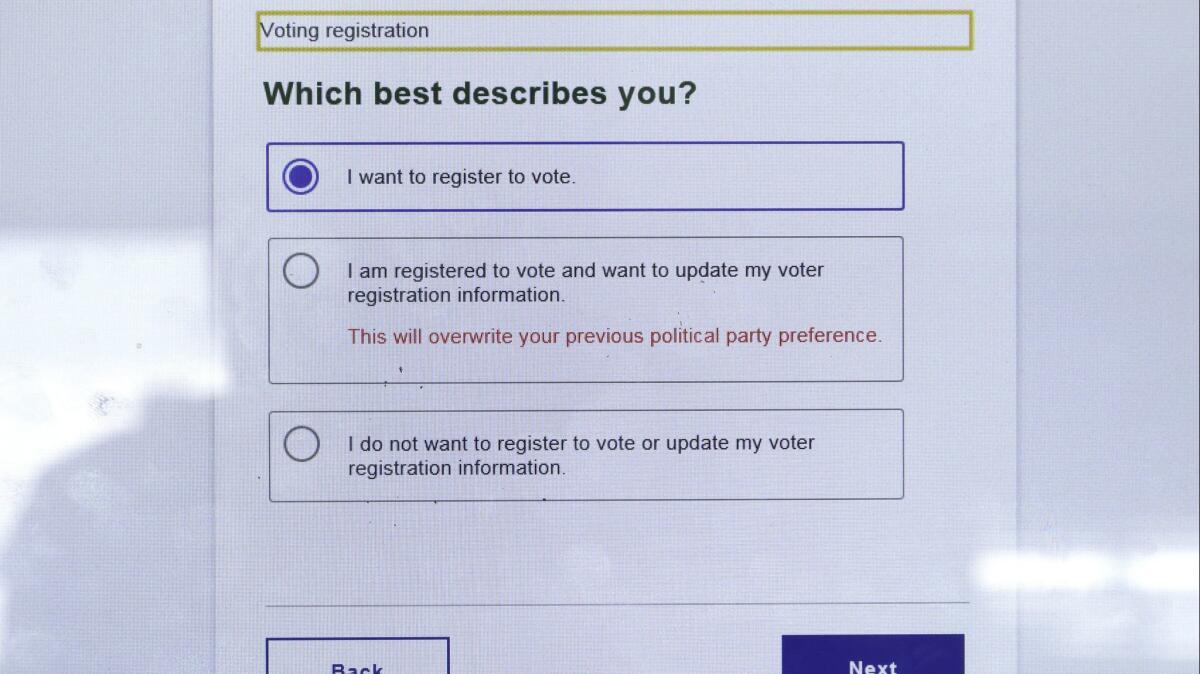

Touchscreen devices at DMV offices seemingly changed customer selections from registering to vote to “I do not want to register to vote or update my information.” When discovered, two state engineers told The Times, some files were manually “corrected” — even though questions lingered about the customer’s intent.

Touchscreen problems were also the source of frantic emails among top DMV officials regarding the potential for identity theft — the screens weren’t clearing personal data between customer appointments. Here again, physical testing of the devices was limited to a single four-hour session the day before launch, probably insufficient to catch potential shortcomings.

Officials later discovered a problem with incorrect county information, thus sending a voter’s new or updated registration to the wrong location. The mistake was brought to the attention of Padilla, told by a top advisor to Gov. Brown in an April 28 email that there would be a “remedy for this issue as quickly as possible.”

Problems arose, too, after DMV officials turned on the system’s second phase: internet registration and change-of-address functions. On May 1, a DMV official wrote that there were “defects” including “errors in reporting eligibility information.”

CDT officials hurriedly brought in new outside programmers who had worked on healthcare.gov and other national projects and were considered to be crisis experts. Contracts totaling $250,000 were awarded to the two companies involved, Layer Aleph and Open Lattice. Neither company is still working on the voter registration project.

In the first two days of operations, the DMV sent more than 35,000 voter records to state elections officials. By the end of the first month, the total was more than 313,000.

Errors by DMV field office employees were later cited as the cause of some 23,000 registration errors. But other mistakes may be attributable to the fact that multiple state government teams were involved with no clear leadership structure. CDT officials said it was the DMV’s job to train its employees, for example, but the physical equipment needed for that training was developed by the CDT.

Baccigalupi, who left the project shortly before launch, said she had urged project leaders to launch the online registration system first — and not the more complicated task of in-person DMV appointments.

“They rolled out in exactly the way we told them not to,” she said.

Nor was there consistent oversight about data security. In August, a CDT employee mistakenly deleted official online voter and license data while using his laptop. A department spokesperson told The Times the mistake was quickly fixed and that rules were subsequently changed to ensure that employees could only read — not actually delete — the original information.

Through February, the new motor voter system had been used for more than 6.7 million transactions. The majority were either people updating their voter registration or opting out of the process. About 1 million new voters were registered.

Padilla, one of the system’s most visible supporters, admitted to frustrations with the program — which led him last year to withdraw his support for Shiomoto, the former DMV director.

“To this day, I believe California motor voter has been an overwhelming success,” he said. “Perfect, flawless rollout? No.”

California’s Little Hoover Commission, an independent oversight agency, urged state officials last fall to ensure that the voter registration system’s problems are fixed.

“Otherwise,” the commission’s report concluded, “the rich diversity of California’s population will be limited in voice and fairness, and the legitimacy of elections called into question.”

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter and sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.