A record number of women are running for office. This election cycle, they didn’t wait for an invite

- Share via

A record number of women are running for the U.S. House, Senate and state legislatures this year — more than any other election in U.S. history.

Traditionally, the major political parties scout out their potential candidates. And typically, says Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, men are sought after more than women.

But in the two years before the 2018 midterm election, amid marches for women’s rights and the growing #MeToo movement, something shifted in a field that has historically paved an easier path for men:

“Women are running whether or not Democrats and Republicans invite them to,” said Ange-Marie Hancock Alfaro, a political science professor at USC.

Alfaro attributes the record-breaking turnout in large part to a groundswell in localized programs encouraging women to run and educating them on the process.

Emily’s List — the leading nonprofit to help and recruit progressive Democratic women to run for office since 1985 — has played witness to that rise in interest. (Emily stands for “Early Money Is Like Yeast — it makes the dough rise.”)

“Recruiting means just that — going out to find women to run,” said Emily Cain, the group’s executive director. “But in our history — the first 30-some years — we were not inundated with women coming to us to run for office.”

That changed in 2016.

Women are running whether or not Democrats and Republicans invite them to.

— Ange-Marie Hancock Alfaro, political science professor at USC

In the first few weeks after President Trump was elected over Hillary Clinton, about 1,000 women reached out to Emily’s List about running for office. The group’s record until then had been 920, and that covered from 2014 to 2016. By the end of 2017, as the #MeToo movement exploded and Women’s March anniversary rallies were planned throughout the country, the record was shattered again with more than 25,000 women signing up online to learn about running for office.

Since Trump’s election, Emily’s List says, more than 40,000 women have expressed interest in running for office.

Cain says healthcare in the age of Trump was a big factor for some women. In 2018, after the Parkland, Fla., school shooting, gun control was also at the forefront.

Emily’s List has had to increase its staff and expand its office space.

“This isn’t a wave,” Cain said. “It’s a sea change.”

A record 3,379 women have won nomination for state legislatures across the country, breaking 2016’s record of 2,649, according to the Center for American Women and Politics. And 235 women won nominations in U.S. House races, breaking the previous 2016 record of 167. Twenty-two women won major-party nominations for U.S. Senate, breaking the record of 18 set in 2012.

Sixteen women have been nominated for gubernatorial races. The previous record, set in 1994, was 10. For the first time in general election history, there are two female congressional candidates facing each other in at least 28 major-party matchups. The previous record, set in 2002 and matched in 2016, was 17.

According to David Wasserman of the Cook Political Report — a nonpartisan group that analyzes campaigns and elections — women have won 43% of Democratic House primary races, and Republican women have won 13% of their party’s primaries.

Alfaro says women don’t often run until they’re “120% ready.” Men, on the other hand, jump in at much earlier stages in their career, she said.

That can be said of fields beyond the realm of politics too. A statistic that has been widely cited in articles and books like Sheryl Sandberg’s “Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead” is that women typically apply for a job when they meet 100% of the qualifications, whereas men often apply when they meet 60%.

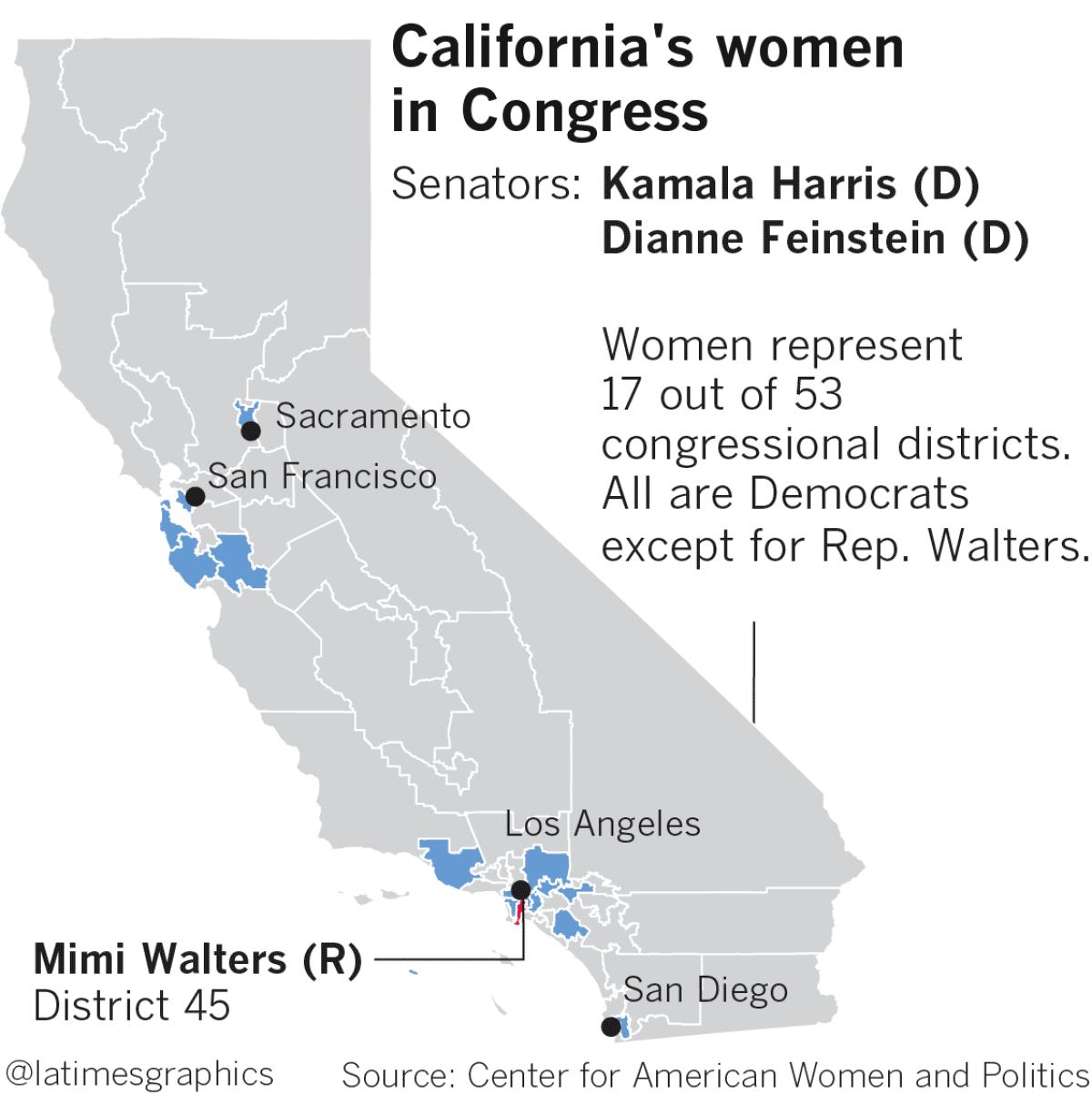

That reluctance helps lead to the imbalance in gender representation. Take California, for example. The Center for American Women and Politics ranks the most populous state at No. 26 for representation of women in the state legislature (25%) compared with the proportion of women in the state (50%).

In 1992, women ran for election in the U.S. in record-breaking numbers. The impetus for the so-called Year of the Woman was Anita Hill’s testimony during the Senate confirmation hearings for then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. Hill, a law professor, had accused Thomas of sexual harassment. Testifying before an all-male panel, she answered questions that attempted to undermine the veracity of her accusations. Ultimately, Thomas was confirmed to the court. And women who saw their gender underrepresented during the hearing were inspired to run.

Walsh emphasizes the fact that although their numbers jumped in the House and Senate that year from 32 to 54, women still accounted for fewer than 10% of members of Congress.

Now there are 84 women serving in the House, out of 435 members, and 23 in the Senate, out of 100.

Although the number of women running in 2018 is impressive, she worries that if women don’t double their representation in Congress this election cycle, it could be perceived as a failure. But it wouldn’t be, she says.

“There are other ways of measuring success,” she said. “I’m trying to not be totally driven by the numbers.”

Women have already made significant firsts

In May, Democrat Liuba Grechen Shirley — a candidate running against Republican Rep. Peter T. King in New York’s 2nd Congressional District — petitioned the Federal Election Commission to allocate campaign funds for child care. The FEC approved, marking a change that could open the door for any parent running at the federal level.

“These kinds of things do have the potential to change fundamentals that could shift the paradigms,” Walsh said.

Former Michigan state Rep. Rashida Tlaib is set to become the first Muslim woman elected to Congress after winning the Democratic nomination to fill the seat of former Rep. John Conyers Jr., who resigned amid sexual harassment allegations. Tlaib is running unopposed.

These kinds of things do have the potential to change fundamentals that could shift the paradigms.

— Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics

In Vermont, Democrat Christine Hallquist became the first openly transgender gubernatorial nominee for a major party. In Georgia, Democratic former state House leader Stacey Abrams — an Emily’s List-backed candidate — became the first black woman to win a major-party nomination for that state’s governor.

Texas is likely to send its first two Latinas to Congress after state Sen. Sylvia Garcia and former County Judge Veronica Escobar, both Democrats, won their House primaries in districts that favor their party. Arizona will send its first female senator to Congress as Republican Rep. Martha McSally and Democratic Rep. Kyrsten Sinema face off in November.

In New York, activist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez beat Democratic incumbent Rep. Joseph Crowley. In Massachusetts, Ayanna Pressley, the first black woman elected to the Boston City Council, ousted veteran Democratic Rep. Michael E. Capuano in the primary. She’s expected to become the first black woman elected to Congress from Massachusetts; no Republican candidate is running against her.

Beyond election day’s outcome, Walsh says, the big unknown is whether this year’s momentum is a one-off or a new norm that will continue into 2020 and 2022.

“We’re not going to see 240 years of women’s underrepresentation in politics end in one election cycle,” Walsh said.

Twitter: @cshalby

ALSO:

It could be another ‘Year of the Woman’ in California, but probably not

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.