Trump proposed poll-monitoring in urban areas, so black voters are fighting back with monitoring of their own

- Share via

Reporting from Philadelphia — The Rev. Alyn E. Waller was appalled when he learned that Donald Trump was dispatching supporters to Philadelphia to watch for vote fraud on election day.

Most Trump supporters are white. Nearly half of Philadelphia’s population is black. The racial dimension was obvious.

“It is absolutely racist,” said Waller, the pastor of Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church, Philadelphia’s largest black congregation. “He fundamentally believes that we are less than who he is, and therefore capable of robbing and stealing and being dangerous.”

Trump’s slew of inflammatory remarks have led many Americans to see him as a bigot. Since 1968, when segregationist George Wallace of Alabama won five states in the South, no major presidential contender has used such raw rhetoric on race or ethnicity.

That’s why it’s hard for Waller and other leaders of Philadelphia’s black churches and mosques to view Trump’s poll-monitoring plan as anything but an attempt to suppress the black vote. Waller recently convened a group of them, and they agreed to station patrols of up to seven black men at polling stations across the city.

“If it’s an older woman who’s on a cane, if it’s somebody who’s thirsty, if it’s someone who just needs some encouragement — we’re there to do that,” said Waller, 52. “And if anyone comes around to do anything that would deter from the free, fair opportunity to vote, we will shut that down.”

For Michael Rashid, a leader of Masjidullah, one of the mosques forming the patrols, Trump’s aggressive racial politics have stirred painful memories of his upbringing in Birmingham, Ala.

Obstacles to black voting rights were part of the city’s strict regimen of segregation. The white sections of movie theaters, buses and swimming pools were off-limits to Rashid.

“It was apartheid down there,” he said.

Rashid, 69, a retired healthcare executive, was one of hundreds of black children jailed in 1963 for kneeling in the streets of Birmingham to protest segregation in a landmark rebellion led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. His voice cracked as he recalled the relentless trampling of civil rights in the era of Bull Connor, the police chief who turned attack dogs and fire hoses on the children.

“These poor black people who made maybe $10 a week — and I’m not exaggerating — they had to pay a $2 poll tax to be able to vote,” he said. “So that was a great way of holding down the black vote.”

Now, Rashid fears that Trump supporters will deter black voters, especially the elderly, from going to the polls.

“You hear all this rhetoric about these white people going to come down here, and you see on television, Trump people — they carry guns, and they rough people up,” he said.

Trump denies appealing to racism. “I am the least racist person you’ve ever met,” he has repeatedly told journalists who raised the topic.

Trump’s suggestion that urban voters might steal the election comes after months of comments he has made that offended Latinos, Muslims, women and African Americans.

In a recent Washington Post-ABC News poll, Trump drew support from just 3% of black voters. He often argues that African Americans have been failed by Democrats and says they have nothing to lose by voting for him. Trump describes blacks as living in ghettos with bad schools, no jobs and streets so dangerous that people get shot when they walk to the store for a loaf of bread.

Waller, who once ministered in western Pennsylvania steel country, says he believes Trump has been exploiting the fears of Rust Belt whites reeling from decades of factory shutdowns.

“Yes, this country has let them down, but they’ve been tricked into thinking it’s my fault,” Waller said after a Sunday sermon enlivened by a gospel choir. “The race-baiting language has poor, white, uneducated people thinking that their enemy is black and brown people — that we’re the reason that they’re poor and without jobs.”

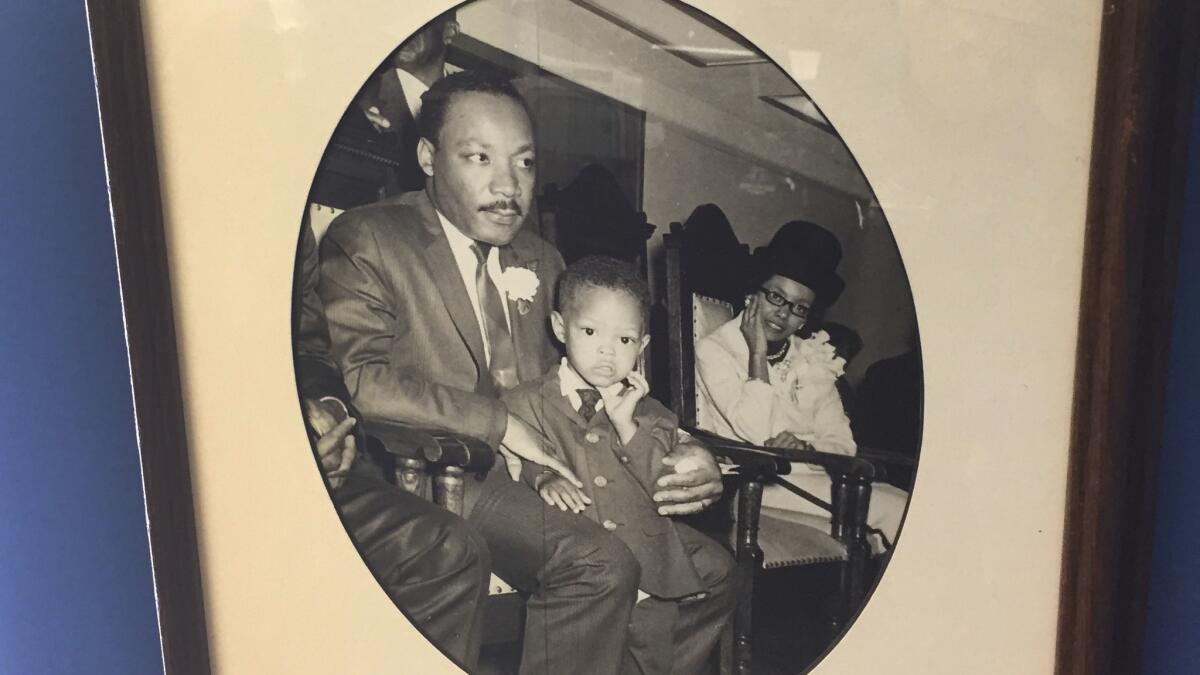

Waller grew up in Cleveland, where his father was pastor of Shiloh Baptist Church. King was a guest preacher at Shiloh in 1967, seven months before his assassination. On the wall facing Waller’s desk at Enon Tabernacle hangs a framed black-and-white photo of himself, at 3 years old, in King’s lap by his father’s pulpit.

“That picture has been either in my bedroom, my dorm room or my office all of my life,” Waller said.

Also on the wall is a photo of President Obama. For years, Trump spread the lie that Obama might be a Muslim born in Africa, challenging him to produce a birth certificate to prove his eligibility to be commander in chief.

It reminded Waller of a white cop demanding a black man’s papers.

Under Pennsylvania law, poll monitors must live in the county where they are watching the vote. But at an August rally in Altoona, Pa., a town that is 94% white and more than 200 miles from Philadelphia, Trump called for volunteers to scout for cheating in “certain parts of the state.”

“We’re going to watch Pennsylvania, go down to certain areas ... and make sure other people don’t come in and vote five times,” he told the crowd. He has made similar appeals several times since, naming Philadelphia, Chicago and St. Louis as cities where he anticipates bogus voting.

Neither Trump’s vote monitors nor the black religious leaders’ patrols would be permitted inside polling places. But both parties are allowed to station state-certified poll watchers inside.

Trump’s threat to dispatch poll watchers to Philadelphia fits a pattern that dates to Reconstruction, said J. Morgan Kousser, a Caltech historian and expert in minority voting rights. Like Jim Crow laws, including the Alabama poll tax that a federal court struck down in 1966, it’s a tactic to impede the right of African Americans to vote, he said.

Republican poll watching a generation ago led to legal trouble. Under a 1982 federal consent decree, the party pledged not to use fraud prevention as a pretext to block people from voting in minority neighborhoods. That court order could apply to Trump’s campaign.

Election 2016 | Live coverage on Trail Guide | Sign up for the newsletter

When Rashid was a boy, his father served as a poll monitor safeguarding the voting rights of black neighbors in Birmingham. At the time, Rashid’s name was Michael Coar. He converted to Islam at 23.

His older brother, David Coar, now a retired U.S. District Court judge in Chicago, remembers the literacy test that Birmingham’s election registrar required him to take in 1964.

A white clerk flipped through a Rolodex of constitutional provisions, plucked a card on war powers and demanded that Coar read and interpret it. “They told me they would notify me within a few days whether I had passed,” Coar said.

He did.

The Voting Rights Act would outlaw literacy tests the following year. At the time, many blacks in the South risked retaliation even for registering to vote. Some were fired from their jobs.

“Going to the polls and voting, it was a big deal,” Rashid said.

Standing up for civil rights was dangerous. The Ku Klux Klan bombed so many houses and churches in the Coars’ neighborhood that it became known as Dynamite Hill. Rashid was friends with three of the four girls killed in the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church.

Rashid remembers sitting on his family’s front porch one time when a car full of white men drove up. “They just sit out there and start looking at us,” he said. “My father goes in the house and comes out with a rifle, and he just sits there and holds his rifle. And they stare at him some more, and then they pull off.”

A few weeks after Rashid’s arrest at the King protest, Wallace — flouting a federal court order — stood in a schoolhouse doorway to block integration at the University of Alabama. Trump shows the same defiant streak and, like Wallace, panders to “a more brutish kind of behavior,” Rashid said. “We’ve been here before.”

Twitter: @finneganLAT

ALSO

The FBI director had a choice in the new Clinton email probe: Follow custom, or go public

Trump has made a lot of women mad. Clinton hopes to turn that into a surge of votes for Democrats

How Michelle Obama became more than just another political voice

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.