From silent dispatch to televised spectacle ā how the State of the Union has evolved

President Trump has spent the last year trampling many of the courtesies and customs associated with his office and the swampy bog, Washington, D.C., he now calls home.

But there is one ritual that holds fast: the State of the Union address, set for delivery Tuesday night to a joint session of Congress.

Vaguely prescribed in the Constitution ā Article II, Section 3, Clause 1, for those keeping score ā the speech fulfills the obligation of the president āfrom time to timeā to give āto the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.ā (And itās been a he, invariably, for the last 229 years.)

The dispatch of that responsibility has evolved considerably over time, from a written message sent inconspicuously to lawmakers to the modern pageant of pomp and punditry that includes wall-to-wall news coverage, a televised response from the opposition party, and no end of carefully considered post-speech reaction from members of the two major parties.

(Spoiler alert: If Trump delivers the speech standing on his head and whistling Bruno Marsā āThatās What I Like,ā Republicans will decree the performance outstandingly presidential. Conversely, he can announce that he single-handedly discovered a cure for cancer and eliminated poverty, and Democrats will express disappointment at his self-centeredness and refusal to reach across the partisan aisle.)

Bruno Mars?

Donāt count on it. The president is expected to hew to a fairly standard script, discussing the political impasse over immigration, outlining an infrastructure rebuilding plan and boasting of the nationās robust economy ā which he will gladly take credit for ā among the usual exhaustive list of topics.

Because Trumpās an old hand at this?

Well, yes and no. The president delivered an address to Congress in February in a fashion identical to the speech he gives Tuesday night. But because Trump had not been in office for a year, it was technically not a State of the Union address. That why this one is being described as his first.

How have other presidents handled the speech?

Bit of a trick question there. George Washington spoke to a joint session of Congress in 1790 in what became the first State of the Union address. But the nationās third president, Thomas Jefferson, discontinued the practice, which was a bit too monarchical for his taste, choosing to dispatch a written message instead.

And thatās the way other presidents handled their congressional updating obligation for well over a century, until Woodrow Wilson came along and, in 1913, traveled to Capitol Hill to speak to lawmakers directly.

Why, after so many years, did he do that?

Begging indulgence, Wilson said the list of topics he needed to cover was simply too long and matters were too important to submit in abbreviated written form. But Wilson also had a political motive, believing it was important to elevate the stature of the presidency and, he hoped, give a boost to his progressive political agenda.

Did Wilson tweet his remarks or post them on YouTube?

Uh, no.

Sad!

Getting a bit ahead of things there, though new media have certainly had a considerable impact.

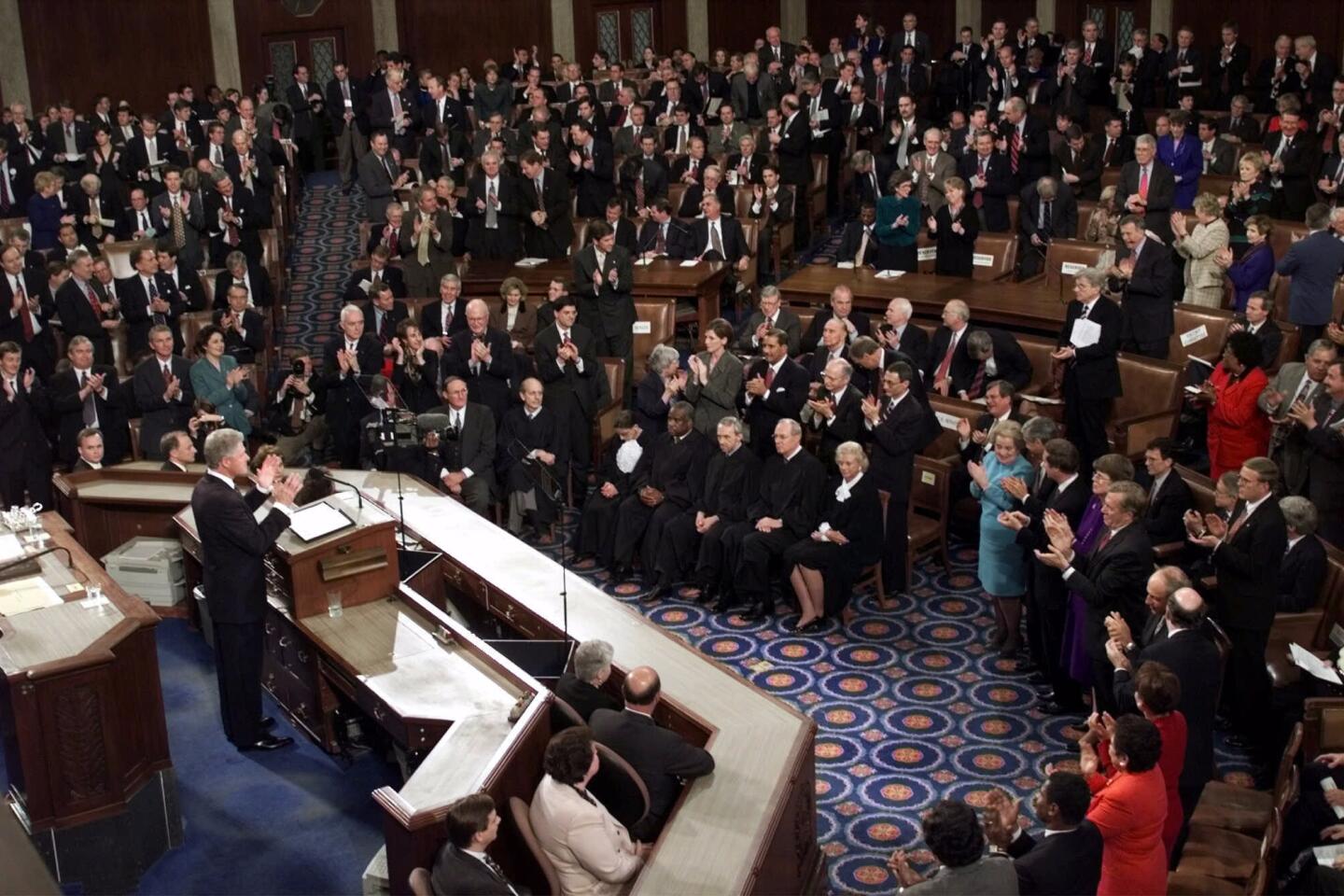

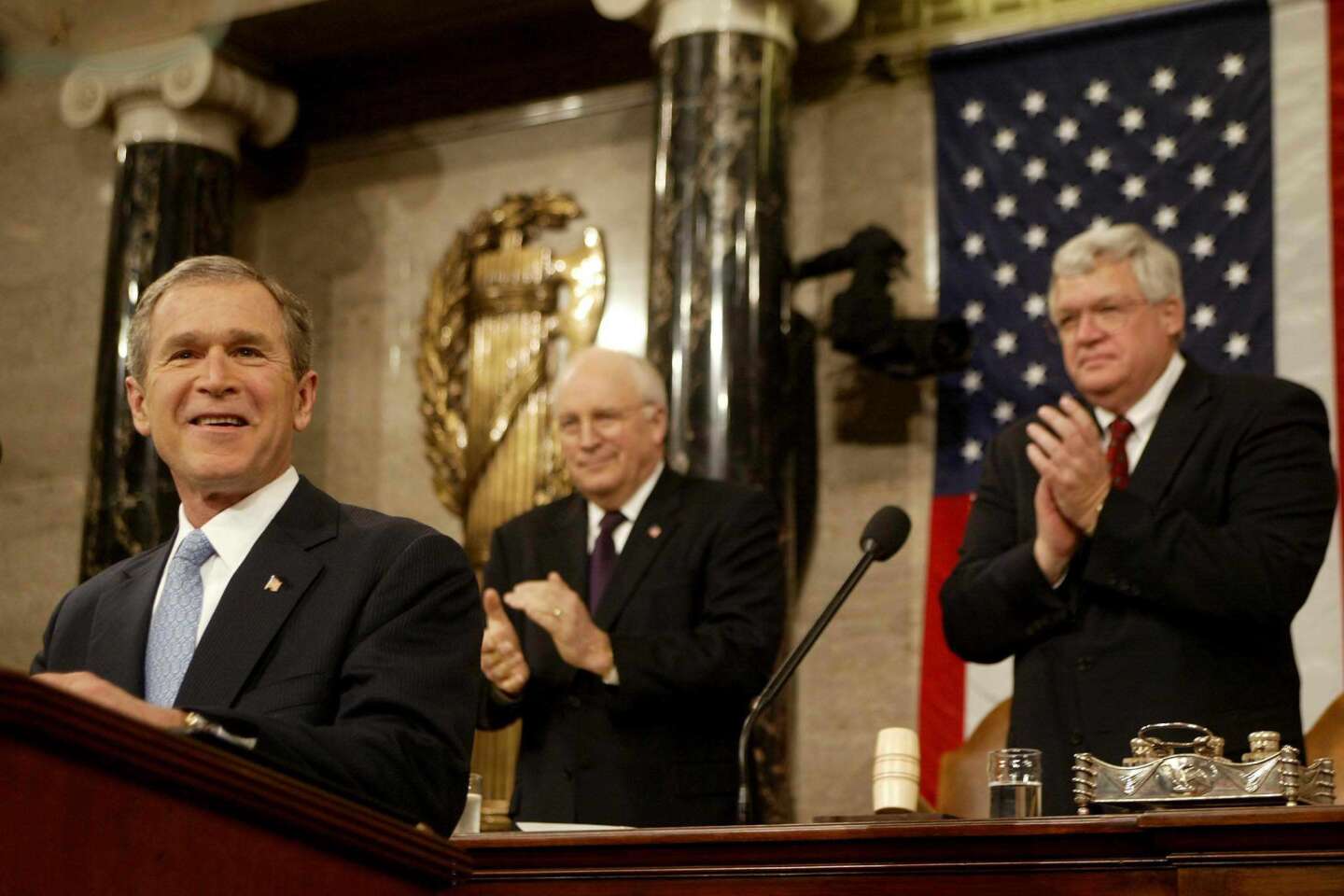

In 1923, Calvin Coolidge delivered the first State of the Union speech carried on radio, and in 1947 Harry Truman delivered the first televised address. Lyndon Johnson gave TVās first prime-time speech in 1965 and Bill Clinton delivered the first address live-streamed on the internet in 1997.

Over time, changing technologies have expanded the presidentās reach and, with it, the import of the speech. Today, tens of millions of people tune in on various media platforms, making the annual address to Congress one of the most widely followed and significant political events of the year.

Thereās certainly a lot of theatrics involved. How about substance?

There are quite a few speeches that stand out for their import. The Monroe Doctrine, warning European powers against meddling in affairs of the Western Hemisphere, was enunciated by James Monroe in his 1823 message to Congress. In 1862, Abraham Lincoln used his annual dispatch to press the case that abolishing slavery was integral to preserving the Union.

Fast-forwarding to the modern era, in 1941 Franklin D. Roosevelt outlined the āfour essential human freedomsā ā freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear ā he deemed essential to a safe and prosperous world. His vision offered the ideological groundwork for liberal policies pursued at home and abroad by subsequent generations of Democratic leaders.

In 1965, coming off his landslide reelection, Johnson outlined portions of the expansive government vision ā increased education spending, anti-poverty initiatives, the Medicare program ā that came to be known as the Great Society.

Just over 30 years later, Clinton ā chastened by a Republican majority in Congress ā declared āthe era of big government is overā and pushed to move his Democratic Party closer to the political middle.

How long does the State of the Union speech last?

Thatās entirely up to the president. The famously loquacious Clinton once spoke for close to an hour and 15 minutes. Richard Nixon was able to knock off most of his addresses in a little over half an hour.

With interruptions for applause and the like, Trumpās speech to Congress last year clocked in at 60 minutes almost on the dot.

And then?

As soon as the president finishes Tuesday night, the official Democratic response, by Massachusetts Rep. Joseph P. Kennedy III, will follow.

No Bruno Mars?

Sorry, no.

Twitter: @markzbarabak

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.