Joe Biden is running for president. Has his time come? Or come and gone?

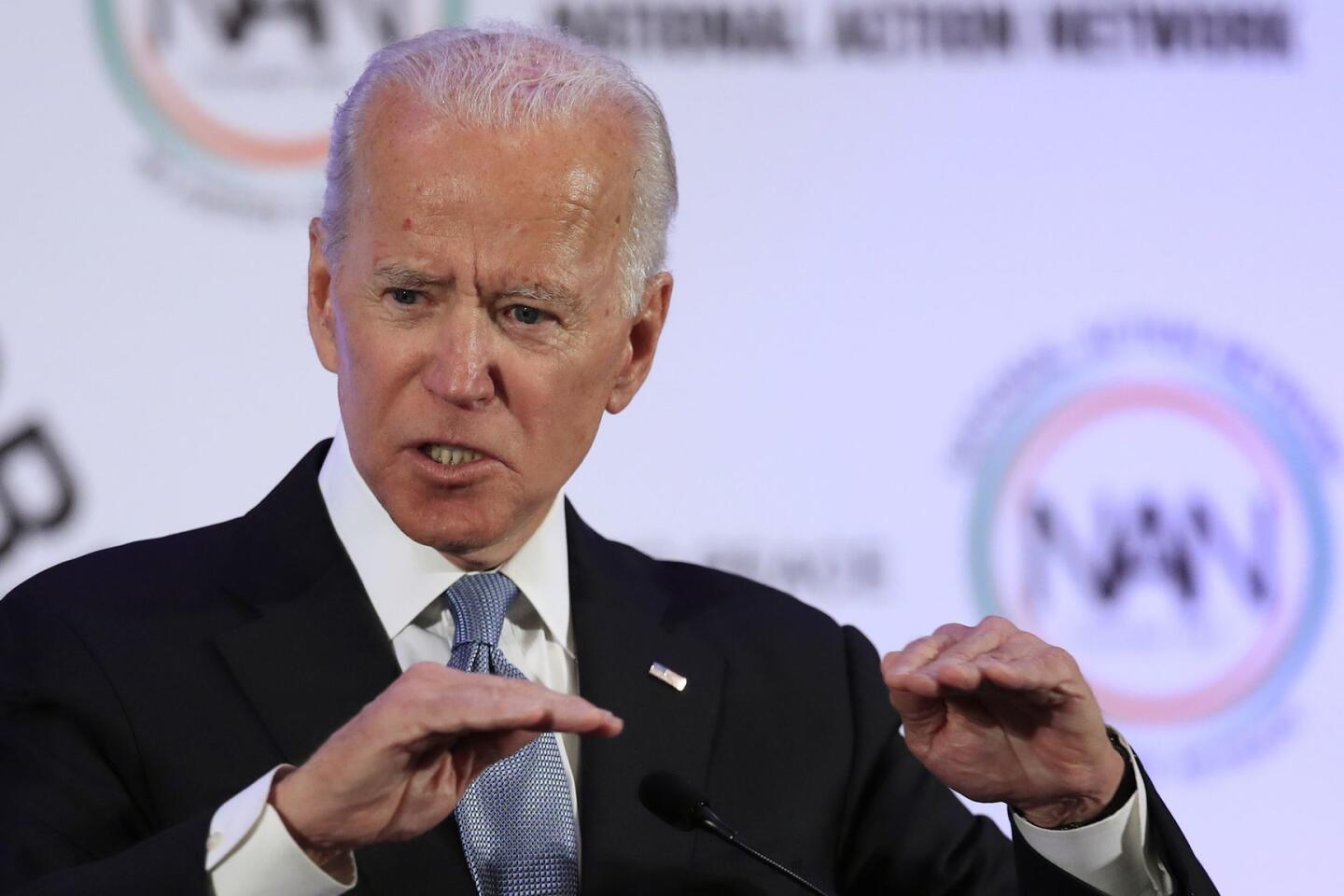

Former Vice President Joe Biden delivered a warning about the risks of reelecting President Trump, focusing on the incumbent more directly than most of his Democratic rivals have done.

- Share via

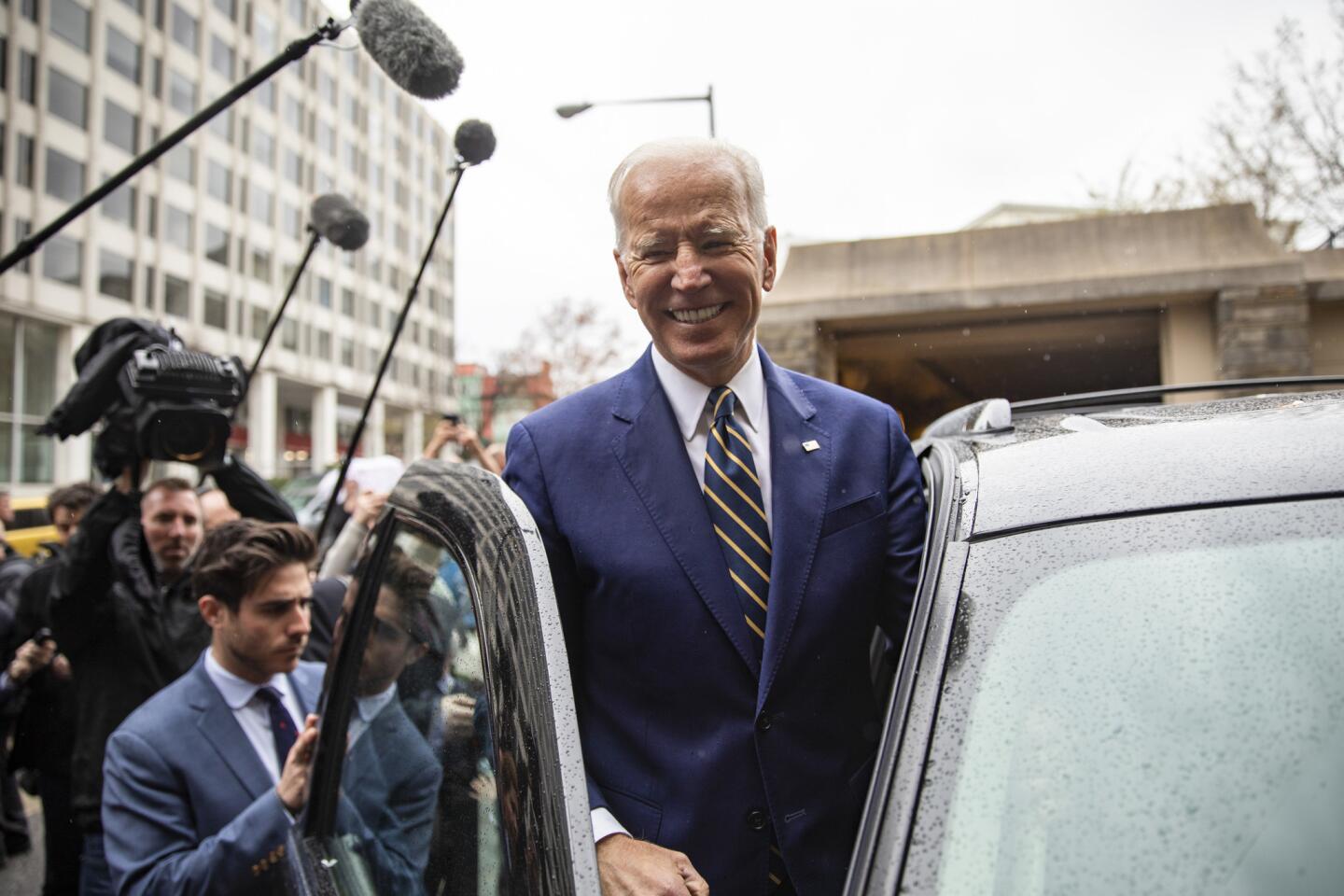

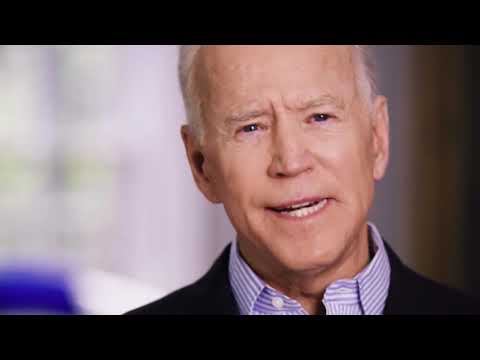

Reporting from Washington — As former Vice President Joe Biden entered the 2020 presidential race Thursday, he immediately looked past the vast field of Democratic rivals and threw down the gauntlet toward President Trump, casting the race as a “battle for the soul of the nation.”

His strategy amounts to a bet that ideology and policy matter less to Democratic primary voters than their desire for victory over a president who has upended social and political values that liberals hold dear.

“If we give Donald Trump eight years in the White House, he will forever and fundamentally alter the character of this nation, who we are, and I cannot stand by and watch that happen,” Biden said in a three-and-a-half-minute announcement video, in which he linked Trump to the violent neo-Nazi demonstration in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017.

Trump responded on Twitter with a message addressed to “Sleepy Joe.”

“I only hope you have the intelligence, long in doubt, to wage a successful primary campaign,” Trump tweeted, adding that “if you make it, I will see you at the Starting Gate!”

Biden’s focus on Trump contrasted with the campaign announcements of most of the 19 other Democratic hopefuls, who have emphasized their own messages over Trump bashing in their efforts to stand out from the crowd.

But Biden has less need to define himself than other candidates, and attacking the president may be more effective now than it was in 2016, when Hillary Clinton focused on Trump’s negatives and lost. Democratic voters have now had a few years to see what the Trump presidency has wrought.

Biden’s video centered on the moment in 2017 when Trump responded to the Charlottesville clash between neo-Nazis and counter-protesters by saying that there were “very fine people on both sides.”

“In that moment, I knew the threat to this nation was unlike any I’ve ever seen in my lifetime,” Biden said.

The video underscored the belief within Biden’s camp that his strongest argument in the primaries will be that the former vice president’s stature and long political experience make him the best equipped to beat the president.

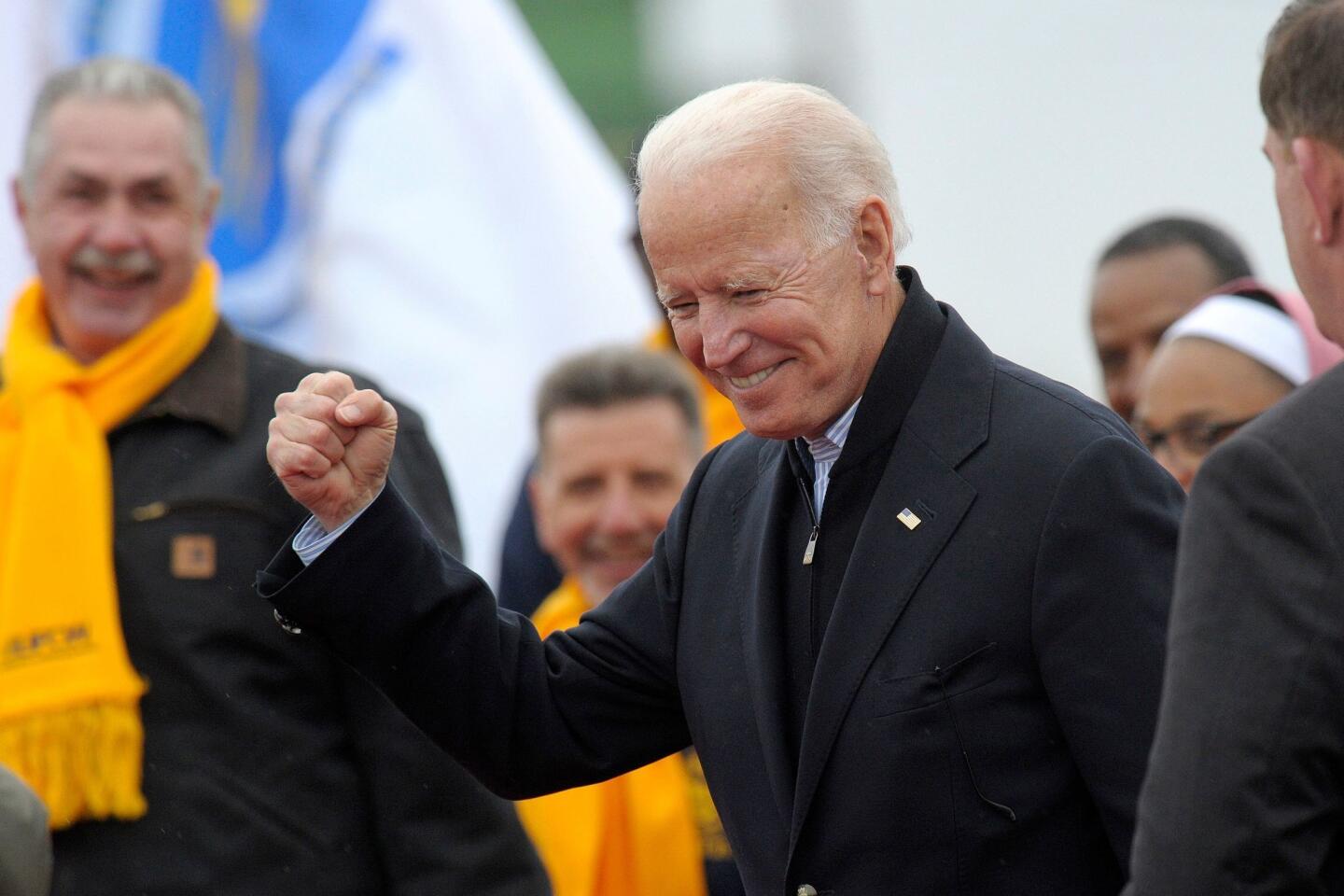

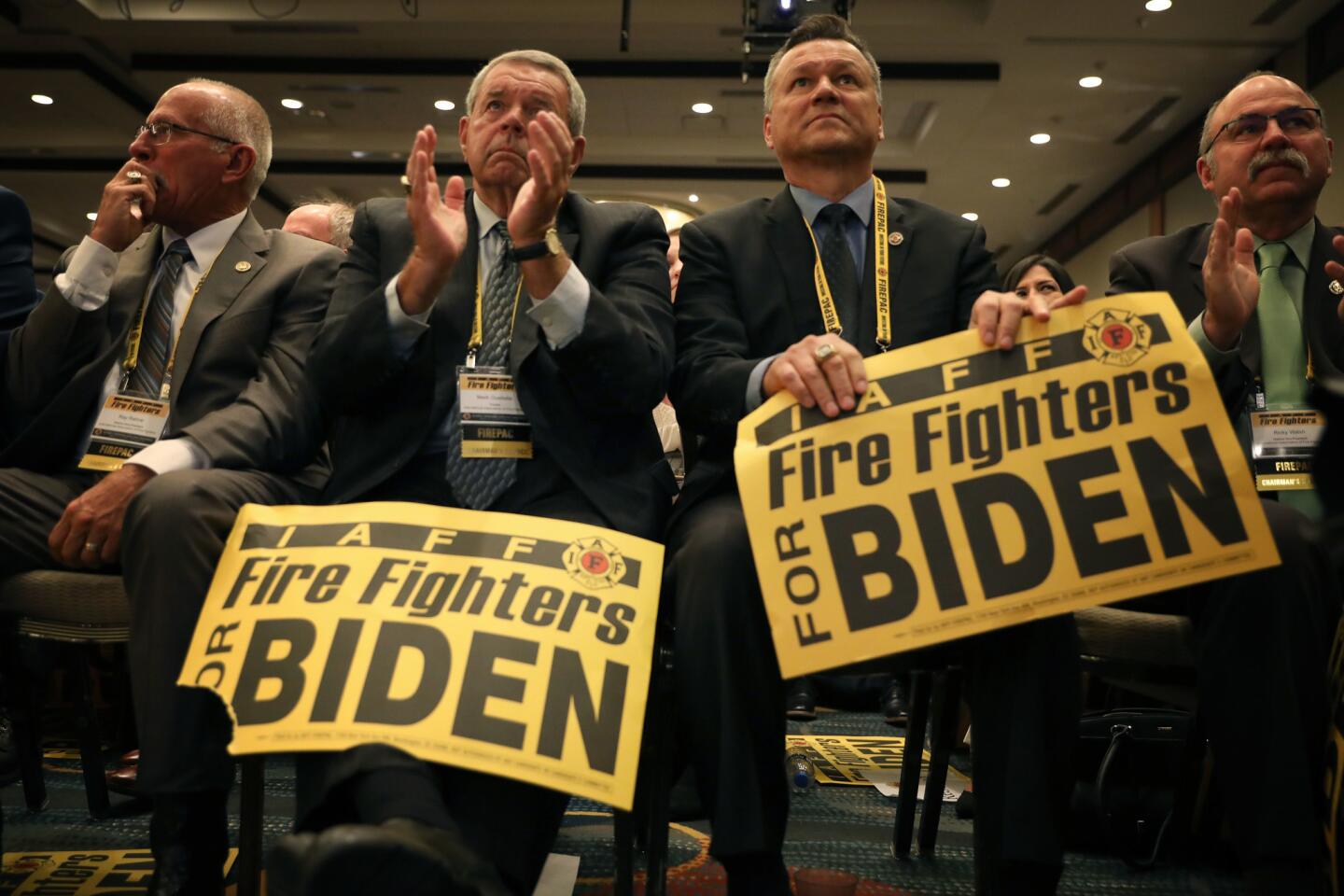

A campaign spokesman said Biden’s message will build on “three pillars” -- the “battle for the soul of America,” spelled out in the video; rebuilding the middle class, which is to be the focus of his first public campaign event Monday at a Teamsters union hall in Pittsburgh; and uniting America, the theme of a big campaign kickoff rally scheduled for Philadelphia on May 18.

The early focus on Pennsylvania is no accident. The state was one of three, along with Wisconsin and Michigan, where narrow Trump victories in 2016 put him in the White House. Biden’s claim to have appeal to working-class voters in those states forms a key part of his pitch to Democratic primary voters.

In the run-up to the Philadelphia rally, the aide said, Biden will also travel to Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Nevada, all states with early contests in the primary season.

Biden has teased his announcement for months, building anticipation. With his near-universal name recognition, vast political network and long government resume — 36 years in the Senate and eight as Barack Obama’s vice president — he has consistently sat atop polls of Democratic voters nationwide and in states holding early primaries.

Now, his official entry into the race has potential to shape it. As a popular centrist well known to most Democrats, he poses an obstacle to lesser-known candidates laboring to gain traction.

He could stand as the principal rival to Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator who has his own large group of committed supporters on the party’s left flank including many who backed his unsuccessful 2016 bid for the Democratic nomination.

Biden armed himself for that rivalry Thursday by announcing as a senior advisor Symone Sanders, an African American who had been a top spokesperson for Sanders in 2016.

A major question is whether Biden can maintain his current level of support once he goes from hypothetical candidate to real competitor.

Biden is renowned for his gaffes in previous presidential races. If he stumbles early, the Democratic campaign would likely become far more competitive and contentious.

In that contest, Biden’s political assets are closely related to his liabilities.

He has the backing of many of the party’s biggest donors, but his reliance on old-fashioned fundraising from top-dollar contributors will contrast with rivals who excel at raising money from the small donors who are increasingly important in today’s Democratic Party.

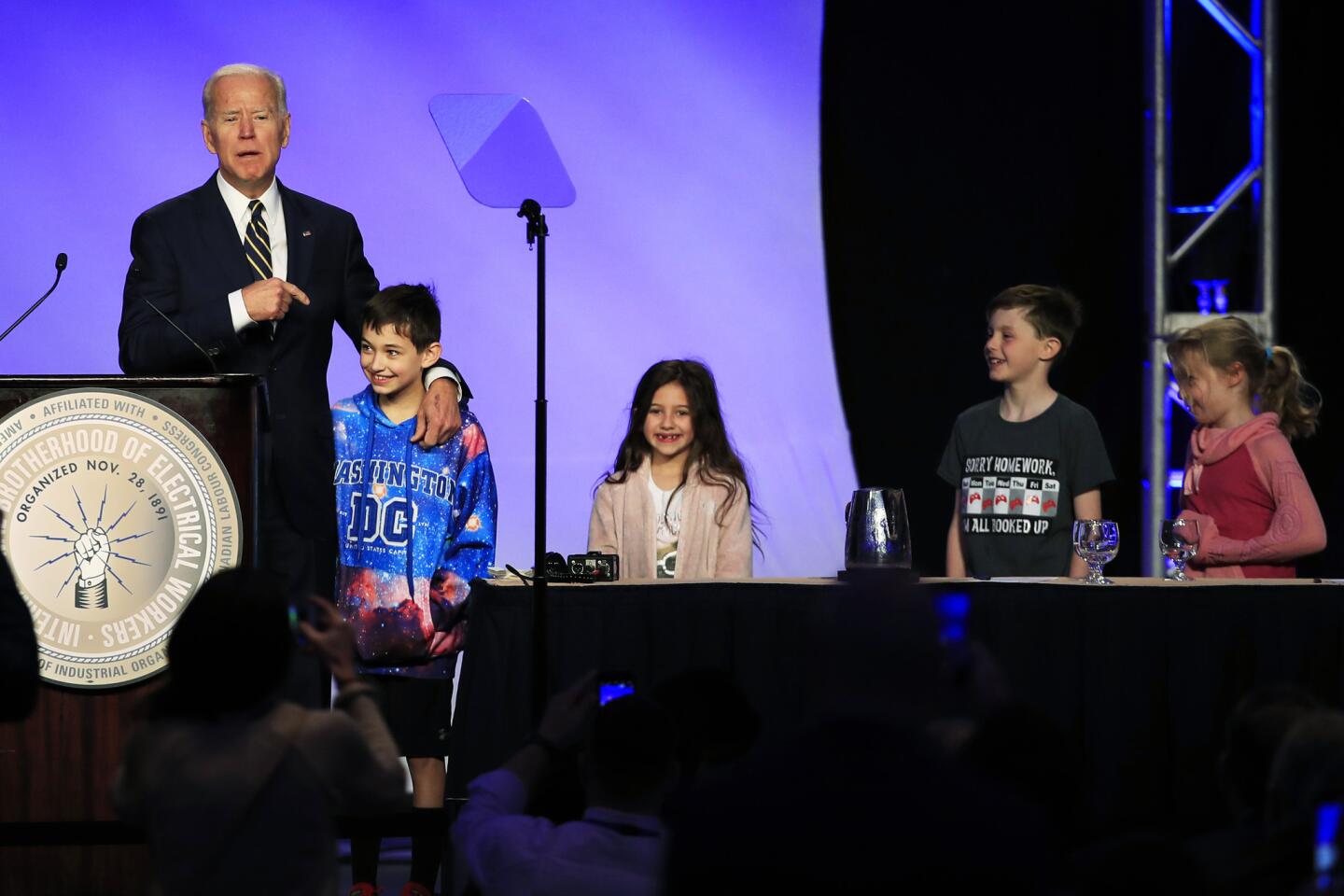

He boasts an easy rapport with many voters, but has already has had to apologize for his old-school style of politicking — which extends from backslapping to hugging and other personal contact that has made some women uncomfortable.

After former Nevada state legislator Lucy Flores and several other women went public with statements about incidents in which Biden invaded their personal space, he released a video acknowledging that “social norms have begun to change” and promising to be more respectful.

Biden hopes to benefit from his association with Obama, who remains extremely popular among Democratic voters, but even that may emphasize a sense of him as a product of the party’s past, not its future.

Obama is unlikely to back any candidate this early in the 2020 primary contest, according to a person familiar with his thinking, because he believes a “robust primary” is good for the party and the candidates. Shortly after the video release, a spokesperson issued a statement that praised Biden but did not endorse him.

“President Obama has long said that selecting Joe Biden as his running mate in 2008 was one of the best decisions he ever made,” said the statement from spokeswoman Katie Hill. “He relied on the Vice President’s knowledge, insight, and judgment throughout both campaigns and the entire presidency. The two forged a special bond over the last 10 years and remain close today.”

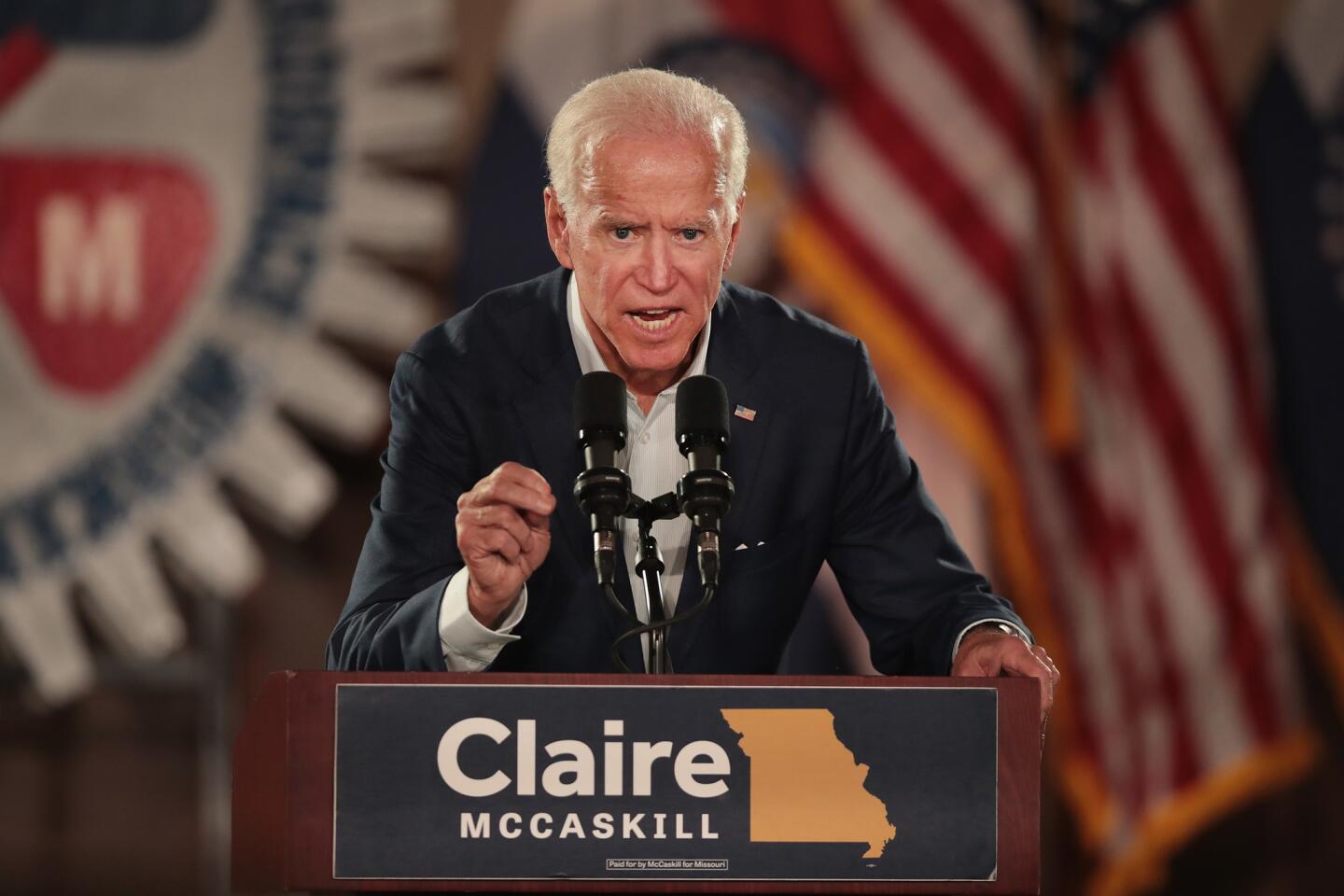

Above all, Biden has a 40-year record of experience, but it is one littered with positions at odds with today’s liberal Democratic consensus.

He supported crime legislation in the 1990s that many blame for the explosion of prison populations. Many women’s advocates faulted him for his role as chairman of the Judiciary Committee during the 1991 Clarence Thomas hearings, saying he did not take seriously enough the sexual harassment allegations lodged by Anita Hill.

A campaign spokesman Thursday issued a statement saying that Biden had spoken to Hill. While not specifying the timing, the statement said: “They had a private discussion where he shared with her directly his regret for what she endured and his admiration for everything she has done to change the culture around sexual harassment in this country.”

Hill did not respond to requests for comment. But she told the New York Times in a Wednesday interview that she was “deeply unsatisfied” with the conversation.

Who’s running for president and who’s not »

Biden enters the race after a midterm election in 2018 that exposed an electorate hungry for new blood.

Justice Democrats, a political group associated with upstart progressives like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, issued a statement opposing Biden, giving a flavor of the challenge he faces from the party’s left.

“The old guard of the Democratic Party failed to stop Trump, and they can’t be counted on to lead the fight against his divide-and-conquer politics today,” said Alexandra Rojas, executive director of the group.

“Joe Biden stands in near complete opposition to where the center of energy is in the Democratic Party today.”

First elected to the U.S. Senate in an upset in 1972 at the age of 29 — he turned 30, the minimum requirement for a senator, a few weeks after the election — Biden came of political age at a time when the gears of government were still greased with compromise and bipartisanship. He rose gradually through the ranks of influential committees on foreign relations and the judiciary.

When he first ran for president in 1988, he had to drop out of a crowded field after a rival campaign caught him plagiarizing part of a speech by British Labor Party chief Neil Kinnock and passed the news to a reporter of what was then seen as a shocking indiscretion. A couple of months later, he nearly died from an aneurysm that might have killed him had he still been campaigning.

He ran again in 2008, only to be overshadowed by the marquee candidacies of Hillary Clinton and Obama, and he withdrew after the contest’s first event, the Iowa caucus. His national career might have ended there, but Obama had taken a liking to Biden and in August picked him as his vice presidential running mate.

In 2016, Biden gave long, anguished consideration to running to succeed Obama but decided against it in the emotional aftermath of the death of his 46-year-old son, Beau, after a grueling struggle with brain cancer.

Those well-publicized struggles and Biden’s affable authenticity form part of his strength. But his personality also carries an ever-present political risk.

His lapses of campaign discipline have produced more than his share of gaffes, including racially tin-eared remarks as recently as the 2008 campaign, when he referred to Obama as “the first mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.”

Biden can be self-deprecating about that — while making the case that his flaws do not look so bad when compared with Trump’s.

“I am a gaffe machine,” he once said, “but, my God, what a wonderful thing compared to a guy who can’t tell the truth.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.