Joe Biden’s nostalgic remark about segregationist senators draws criticism

- Share via

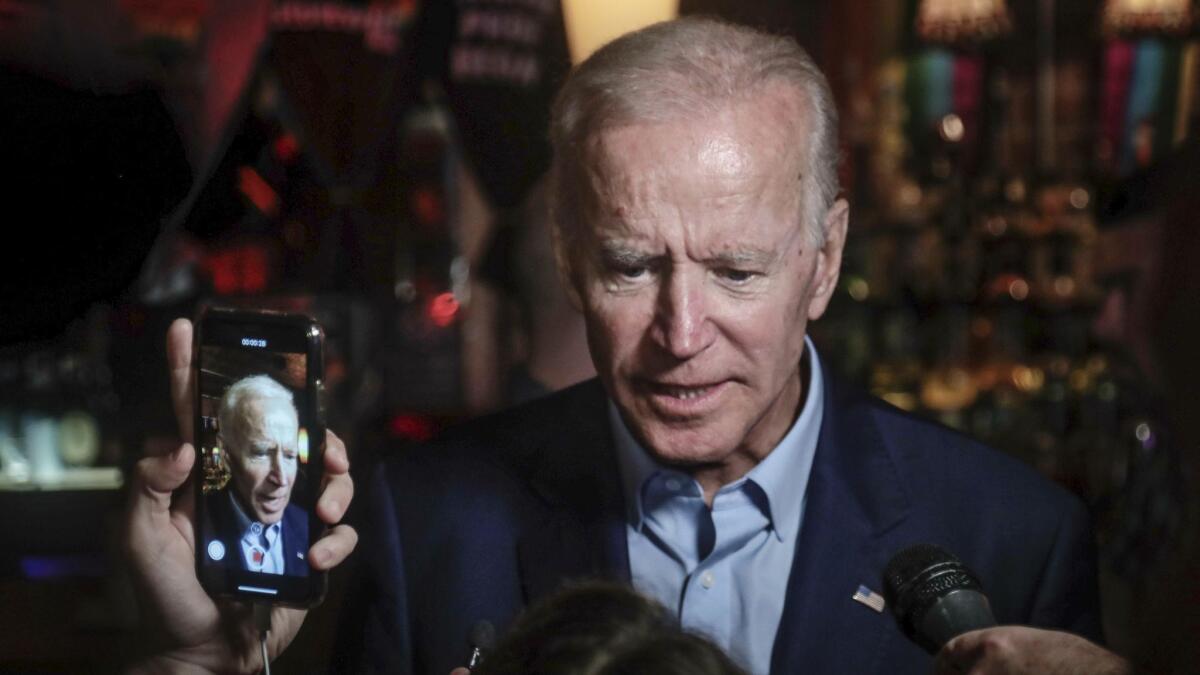

Reporting from Washington — With a tone-deaf bit of nostalgia Tuesday night, former Vice President Joe Biden ignited a fire around his presidential campaign, speaking wistfully of a time in Washington when he could work civilly with conservatives, including arch-segregationist Sens. James O. Eastland of Mississippi and Herman Talmadge of Georgia.

“He never called me boy, he always called me son,” Biden, speaking at a fundraiser in New York said, referring to Eastland.

And while Talmadge was “mean,” he said, “Well guess what? At least there was some civility. We got things done. We didn’t agree on much of anything. We got things done. We got it finished. But today, you look at the other side and you’re the enemy. Not the opposition, the enemy. We don’t talk to each other anymore.”

The response from many Democrats was quick and angry, with Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey, a black rival for Democrats’ 2020 presidential nomination, and others accusing Biden of racial insensitivity. By Wednesday afternoon, the fight had become one of the most heated intra-party disputes of the 2020 Democratic primary campaign.

The controversy goes beyond Biden’s well-known penchant for verbal gaffes because it directly involves one of the central tenets of his campaign — his call for a return to the bipartisan style of governing that prevailed in the Senate in the past.

The timing increases the likelihood that Biden’s embrace of that approach to governing will become a focal point of next week’s first presidential primary debate.

That theme has appeal for voters who long for an end to Washington’s gridlock, but for many Democrats, especially on the party’s left, it underscores Biden’s image as a figure of the past, out of touch with today’s hyper-partisan realities and unwilling to challenge entrenched interests to achieve the party’s objectives.

“Vice President Biden’s relationships with proud segregationists are not the model for how we make America a safer and more inclusive place for black people, and for everyone,” said Booker. “I’m disappointed that he hasn’t issued an immediate apology for the pain his words are dredging up for many Americans. He should.”

Biden, bridling at the suggestion that he sympathized with racists, responded to the controversy late Wednesday by describing his record of pushing for civil rights and voting rights legislation.

“I could not have disagreed with Jim Eastland more,” he said, speaking to reporters outside a fundraiser in the Washington suburbs.

Asked whether he would apologize for his comments, as Booker was requesting, Biden said, “Why should I? Cory should apologize. He knows better. There’s not a racist bone in my body. I’ve been involved in civil rights my whole career.”

Others who criticized Biden included Sen. Kamala Harris of California, the other black candidate in the 2020 field, who told reporters on a Senate elevator Wednesday that Biden’s remark about segregationists “concerns me deeply.”

“If those men had their way, I wouldn’t be in the United States Senate and on this elevator right now,” she said.

Some critics even suggested the remark should disqualify Biden for the party’s nomination.

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, who is married to a black woman and has two biracial children, said on Twitter, “It’s past time for apologies or evolution from @JoeBiden. He repeatedly demonstrates that he is out of step with the values of the modern Democratic Party.”

Connie Schultz, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who is married to Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio, said on Twitter: “That segregationist never called you ‘boy’ because you are white. If you want to boast about your relationship with a racist, you are not who we need to succeed the racist in the White House.”

The episode was reminiscent of the 2002 controversy that forced GOP Sen. Trent Lott of Mississippi to step down as Senate majority leader after he expressed sympathy for the segregationist presidential campaign that Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina ran decades earlier.

Others came to Biden’s defense, including several black lawmakers. House Majority Whip James E. Clyburn (D-S.C.) noted that he worked with Thurmond, his state’s senior senator and a staunch segregationist for much of his career, “all my life.“

“You don’t have to agree with people to work with them,” Clyburn told Politico.

But the issue Biden faces extends beyond his comments about working with segregationists. It goes to the heart of his argument for why his background uniquely qualifies him for the presidency — his claim that he has a particular skill at striking deals.

Already, Biden’s critics and rivals had begun to challenge him on that and on his assumption that the GOP will be more amenable to compromise after Trump leaves office.

“That is a hopelessly naive view,” said Sen. Michael Bennet of Colorado, one of Biden’s 2020 rivals.

Then-President Obama had predicted that Republicans’ “fever” of obstructionism would break after he was reelected in 2012, Bennet recalled.

“The fever did not break when he was re-elected, and it has not broken,” he said in an interview.

Former Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid of Nevada had praise for Biden but was pessimistic that the next Democratic president could work constructively with the GOP.

“I have great confidence in his personality and experience; if anyone can do it Joe Biden can,” said Reid in an interview. “But he has a great big boulder to push up the hill.”

When Biden’s public career began in the 1970s, the two parties overlapped ideologically and partisanship in elections was low. By contrast, the two parties now are ideologically distinct, and partisan voting stands at a high point.

Nonetheless, many polls show a majority of voters want to elect a bridge-builder and like the idea of bipartisan compromise. Biden’s message could be powerful in a general election against President Trump, the most polarizing president in generations.

An NPR/PBS/Marist poll earlier this year found that 63% of Americans, including 70% of Democrats, said they liked elected officials with whom they disagree. Less than a third said they liked officials who only stick to their positions.

Biden presents himself as especially equipped to move the country forward not because of his long-ago relationships with senators like Eastland but because of his more recent experience cutting legislative deals while he was vice president. In the White House, Biden was known as the “McConnell whisperer” for his ability to work with Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky.

“Folks, I believe one of the things I’m pretty good at is bringing people together,” Biden said at Tuesday’s New York fundraiser. “Every time we had trouble in the administration, who got sent to the Hill to settle it? Me… because I demonstrate respect for them.”

Many in his party’s progressive wing believe, however, that he consistently gave up too much to McConnell in those negotiations.

“It’s easy to make deals when you give everything away, and that was how he operated,’’ said Adam Jentleson, a former top aide to Reid. “Democrats made out much better on the deals where he was kept away from the negotiating table than when he was at the table.”

When Biden and McConnell teamed to cut a big deal in 2011 to keep the debt limit from being breached, half of the House Democratic Caucus voted against it.

In a big 2012 negotiation over the looming expiration of the Bush-era tax cuts, Reid was furious when Biden dropped in at the last minute to deal directly with McConnell and accepted a deal that locked most of the tax cuts into law for years to come.

Reid declined to comment on the episode, but people close to him said he felt so burned that when the next big budget face-off came, he asked the White House not to send Biden to negotiate.

Republicans who have dealt with Biden in Congress say he is justified in bragging about his ability to work across the aisle.

“He played a role during that time period of necessity -- being able to speak with Republicans -- because he was the only one in the Obama administration that had the capacity to do it,” said Josh Holmes, a longtime McConnell advisor. “But if you are a dogmatic liberal, he’s not your guy to hold the line down.”

Jason Furman, who was Obama’s chief economic advisor, said liberal complaints about the compromises Biden struck were predictable. Any compromise leaves people on both sides dissatisfied.

“He’d get a very good deal, then had to face the Democratic caucus to sell it,” said Furman. “He absorbed the ire.”

Furman said those skills will continue to be valuable if, as is expected after 2020, the federal government is divided between the parties.

“The skills he’d developed over the last several decades are the same skills needed to govern in divided government,” he said.

Biden acknowledges the skepticism, but says a closely divided country needs deal makers.

“I know the press is, wants to say, ‘There’s nothing can be done, that Biden’s thinking in the past … it can’t happen again,” he said in New York. “Well, folks, if that’s true, we’re finished. We’re in deep, deep trouble.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.