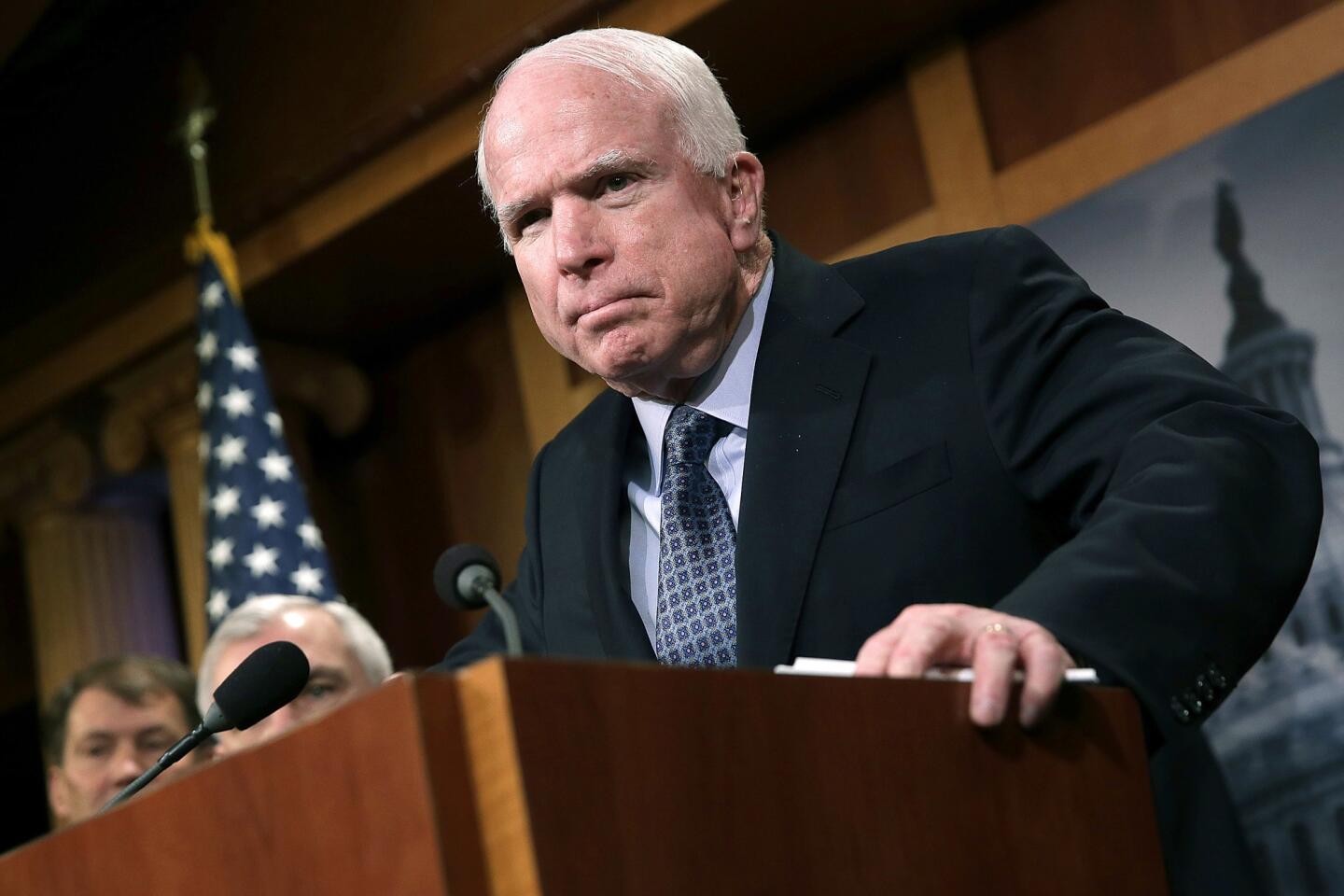

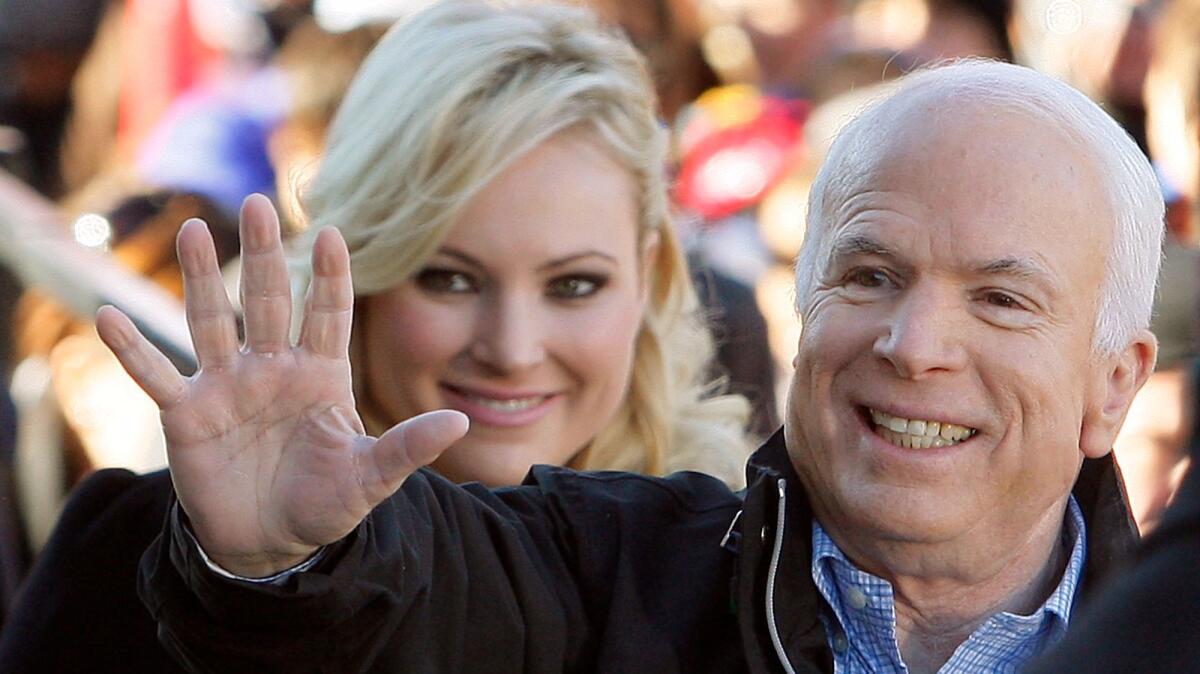

John McCain, war hero, political maverick and GOP standard-bearer, dies at 81

- Share via

Arizona Sen. John McCain, who survived 5½ years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam to become one of the highest-profile, most confounding and pugnacious personalities in American politics — a one-time Republican presidential standard-bearer who alternately trampled and embraced GOP orthodoxy — has died. He was 81.

McCain, who was diagnosed with brain cancer in July 2017, died at 4:28 p.m. Saturday, his office confirmed in a statement. McCain's passing came a day after his family announced he was ceasing medical treatment.

Although he spent more than three decades in Congress representing his adopted home state, McCain was hardly a stamped-from-the-mold politician. At a time when the country grew increasingly tribal and partisan, he drew admiration and antagonism from both parties.

“Warts and all, he was an iconic figure,” said Charlie Cook, a nonpartisan campaign analyst who followed McCain’s political career from the lawmaker’s arrival in Washington in the early 1980s. “As irascible and curmudgeonly as he could be, he was real. There was an authenticity.”

Within moments, tributes began to pour in from across the political divide.

President Trump issued a brief statement on Twitter. “My deepest sympathies and respect go out to the family of Senator John McCain,” he wrote. “Our hearts and prayers are with you!”

President Obama, who defeated McCain in 2008, went on at greater length. “Few of us have been tested the way John once was, or required to show the kind of courage he did,” he stated. “But all of us can aspire to the courage to put the greater good above our own. At John’s best, he showed us what that means.”

McCain had a volcanic temper and an almost demonically willful streak, once describing himself as "one who doesn’t mind getting up on the high wire and doesn’t mind fighting." His career as a hell-raiser in the Navy and iconoclast in the Senate often read more like a picaresque novel than the shelf load of books inspired by his harrowing life story.

In addition to his experience as a prisoner of war, marked by years of torture and solitary confinement, McCain survived near-banishment from the Naval Academy, three plane crashes, a divorce caused by his philandering, a career-threatening Senate scandal, two unsuccessful tries for the White House and a legislative record marked by at least as many setbacks as victories.

He was described (and described himself) as a charmer, a wise guy, an underachiever, a warrior, a hero, a coward, a straight-talker, a shape-shifter and, perhaps more than any label, a maverick.

He was conservative in coloration and stood firmly by his beliefs, even when it contravened the wishes of his party’s leadership. He fought bitterly with right-wing elements of the GOP — over immigration, gay rights, global warming.

In July 2017, he cast the decisive vote killing Republicans’ long-cherished hope of repealing the Affordable Care Act — or Obamacare, as they derided it — marching onto the Senate floor, turning a thumb down and delivering a forceful “no” as the chamber erupted in gasps.

His relationship with Trump was not good. Trump derided his wartime heroism during the 2016 campaign — “I like people who weren’t captured” — and McCain did not hide his contempt.

“Today’s press conference in Helsinki was one of the most disgraceful performances by an American president in memory,” McCain tweeted of Trump’s kid-gloves approach to Russian President Vladimir Putin at a July meeting.

Trump responded in kind. A month later, he pointedly made no mention of Arizona’s ailing senator when he signed the 2019 military appropriation bill — the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act — into law.

McCain unburdened himself at length in “The Restless Wave,” the last of several books he wrote, which was published in May and served as his last political testament.

“He seems uninterested in the moral character of world leaders and their regimes,” he said of Trump. “The appearance of toughness, or a reality show facsimile of toughness seems to matter more than any of our values. Flattery secures his friendship, criticism his enmity.”

A fixture on Washington’s political talk shows and eagerly sought interview in the halls of Congress — ever-ready with a quip or snide observation — McCain’s power extended beyond his role as a committee chairman and aggressive investigator of military spending, influence peddling and pork-barrel spending, among other causes.

He became a leading voice in the Republican Party, especially on military and foreign affairs. (During Senate breaks, he often passed the time visiting war zones and other foreign hot spots.)

And though he faced a number of unsuccessful primary challenges back home, the only time he ever lost an election was when he reached for the White House.

His first run, in 2000, was a joyful, insurgent romp that saw him nearly upset the prohibitive GOP favorite, Texas Gov. George W. Bush, in the primaries. His second try, as the Republican nominee in 2008, was more of a cheerless grind, ending in a decisive loss to Democrat Obama.

Despite his beet-red outbursts — “My temper?” he joked. “I was just exploding about it this morning” — he engendered deep loyalty, forging a bipartisan cadre of friends and trusted advisors who remained close to him for decades. One of them was fellow Vietnam veteran John F. Kerry, the former Massachusetts senator and 2004 Democratic presidential nominee, who briefly considered McCain as his running mate, a highly unconventional move.

To a considerable degree, McCain’s career reflected the Nietzschean notion of that which does not kill us makes us stronger.

Tarred by an influence-peddling scandal, McCain emerged as a champion of open government and campaign finance reform.

As a twice-defeated presidential candidate, he used his new celebrity to heighten his influence in Congress and emerge as one of the GOP’s most prominent leaders.

Although he wished to be known for more than his service in Vietnam and, especially, his hellish captivity, it became the leitmotif of his public life — an irrefutable testament to his personal bravery and excuse for everything from his irksome explosions to the fact he was relatively new to Arizona the first time he sought political office.

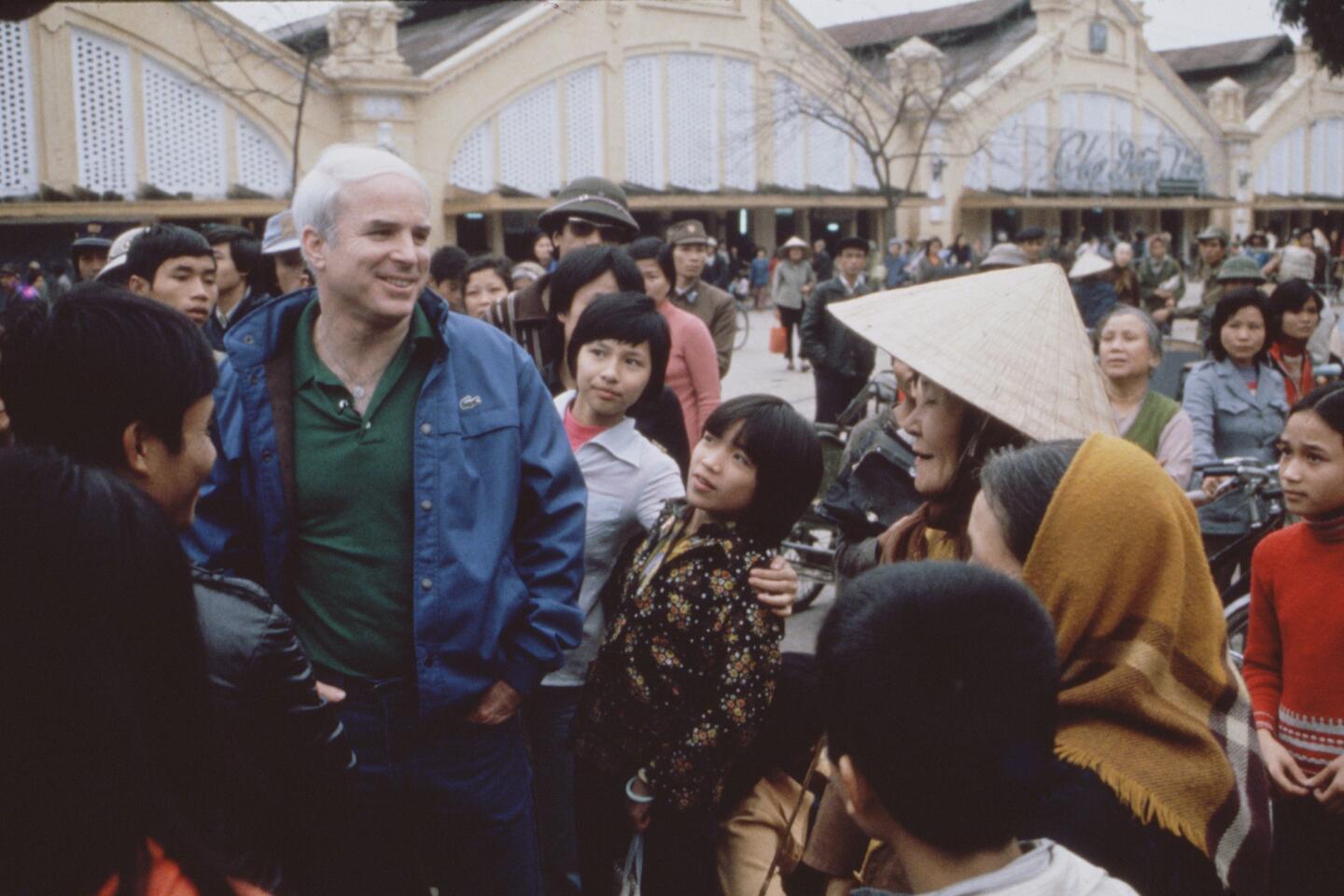

Attacked as an outsider in that 1982 run for the House of Representatives, he brought opponents up short with a blunt and unassailable rejoinder: “The longest place I ever lived in was Hanoi.”

John Sidney McCain III was born Aug. 29, 1936, in the Panama Canal Zone, where his father, a Navy officer, was temporarily stationed. At that instant, his future was seemingly ordained.

As the son and grandson of acclaimed admirals, with a military lineage dating to 17th-century Britain, there was never a question what McCain would do once he grew up, though at times it seemed he was bent more on self-sabotage than extending his family’s proud service.

Relatively small — as an adult he topped out at 5 feet 7 inches — and often the new kid in class, he compensated with a snarling attitude and flying fists. In high school, he was known as “Punk” and “McNasty.” When he graduated from the Naval Academy in 1958, he finished fifth from the bottom of his class but near the top in demerits.

“I was an arrogant, undisciplined, insolent midshipman,” he wrote years later with typical candor. “In short, I acted like a jerk.”

He trained as a naval aviator, surviving three crashes and acquiring a reputation as a pilot who tended toward recklessness. In July 1967, serving in Vietnam’s Tonkin Gulf, he lived through another disaster when a stray electrical charge ignited a missile on the aircraft carrier Forrestal, killing 134 sailors and injuring 161.

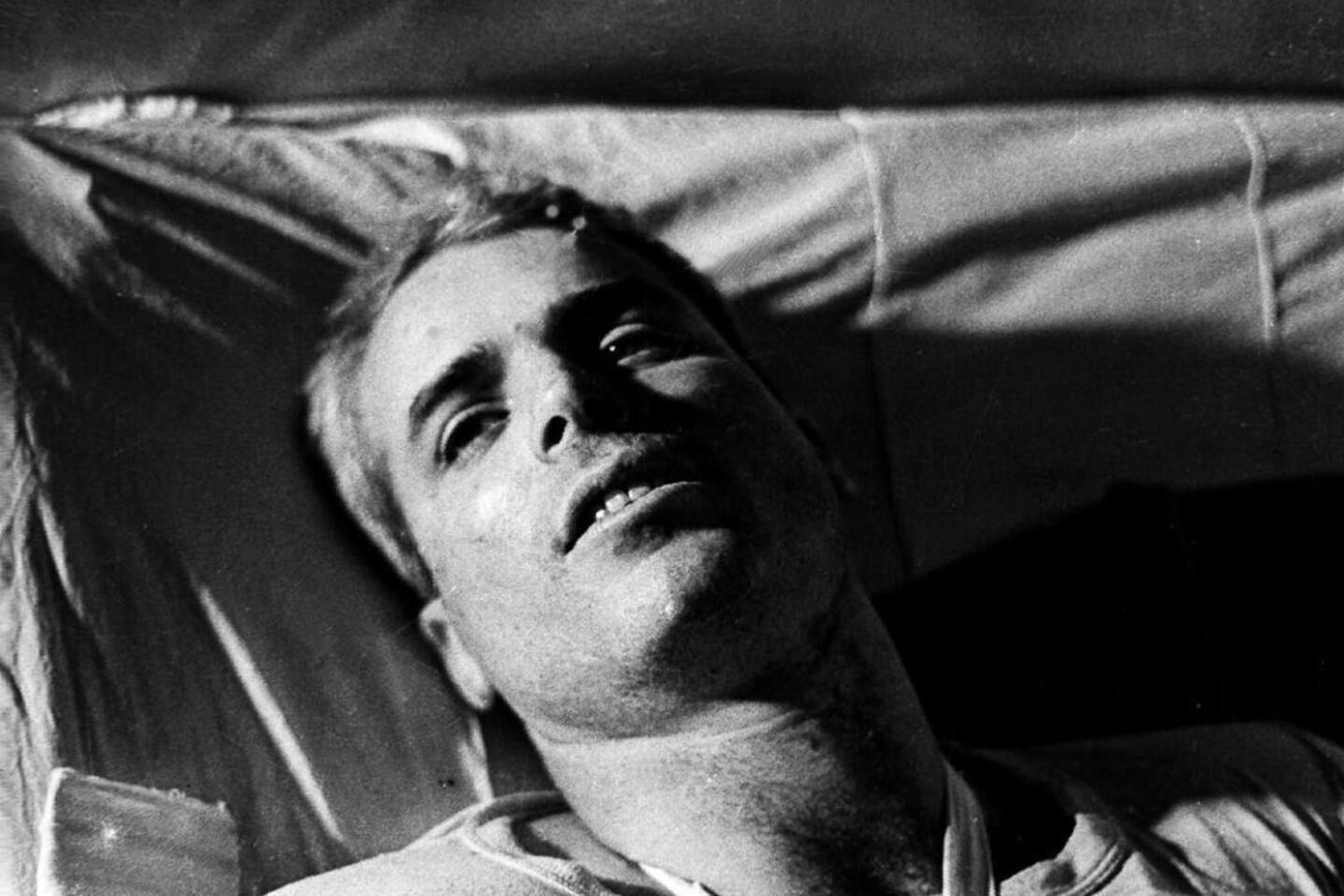

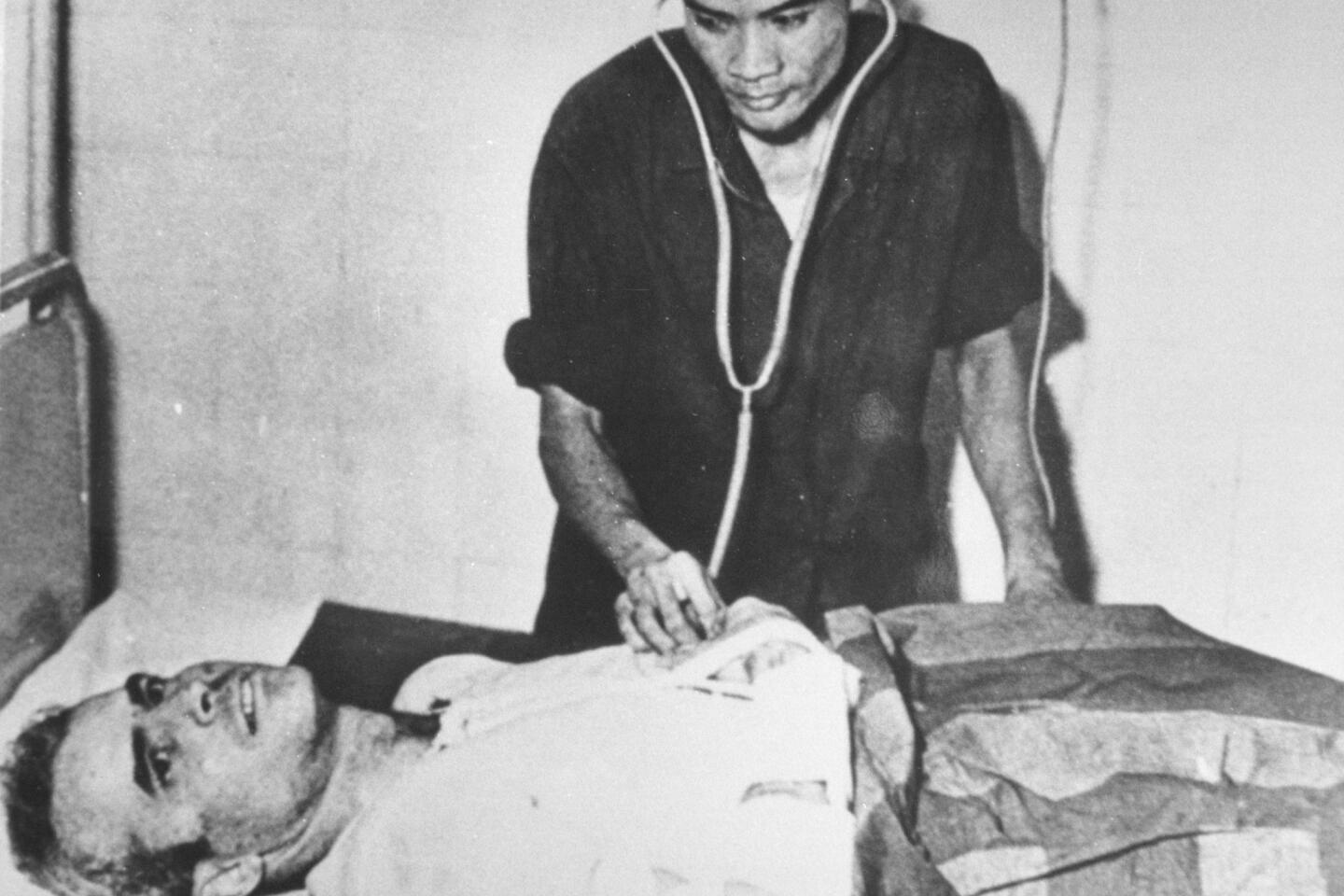

McCain could have returned home but, fatefully, refused. A few months later, on a bombing mission over Hanoi, his A-4E Skyhawk was hit by a missile, which sheared the right wing. McCain ejected and landed, with a broken leg and two broken arms, in a lake in the middle of the North Vietnamese capital.

His captors soon realized they had lucked into a prize possession: the son of a famous American admiral. Seeking a public relations coup — a seeming show of humanitarianism — they offered McCain his freedom. That, however, would have breached the American military code of conduct that required the release of POWs in the order they were captured.

When he refused the offer, his jail keepers were infuriated. “Now, McCain,” he recalled being told, “It will be very bad for you.”

It was.

He endured years of torture and solitary confinement; at one point, after being beaten for days and bound with ropes forcing his head between his knees, McCain broke and signed a taped confession that was broadcast to fellow prisoners: “I am a black criminal and I have performed the deeds of an air pirate.”

He took years to forgive himself, though eventually his dark humor won out. Decades later, a reporter for Esquire was with him when a staffer sought McCain’s advice regarding her son, who was acting up in school.

“Tell him to confess,” McCain told her. “Say, ‘I am a black air pirate and I have committed crimes against the peace-loving people at my school.’ It always worked for me.”

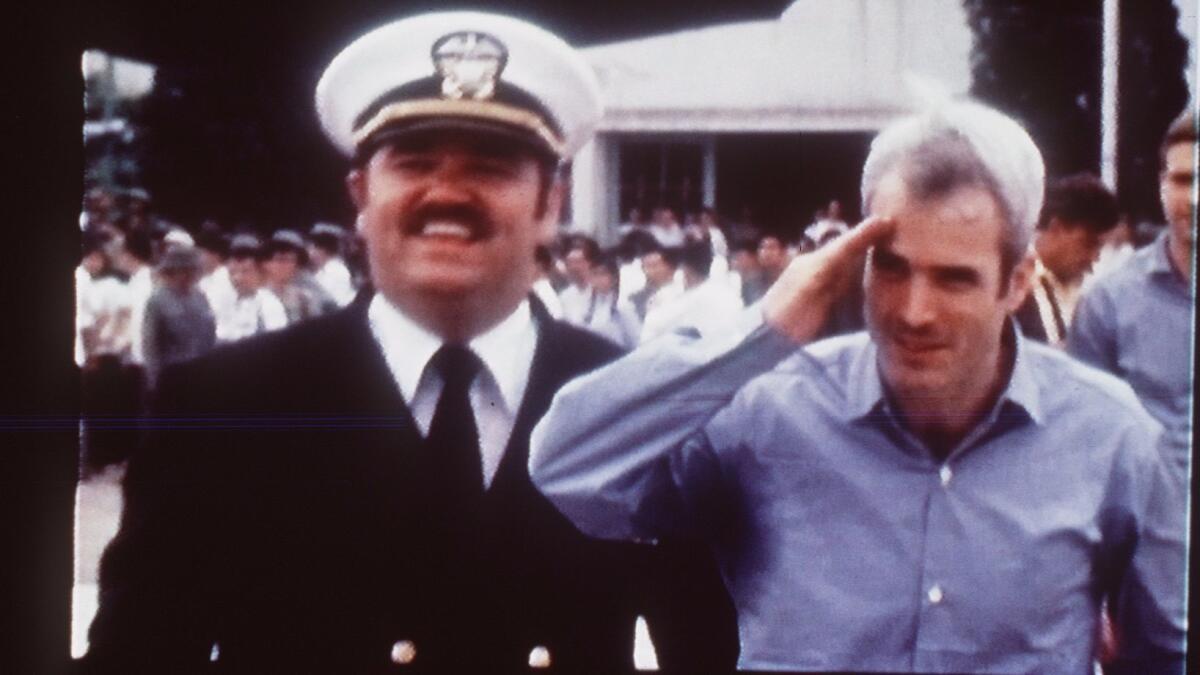

When McCain was finally freed in March 1973, after the signing of the Paris Peace Accord, he walked with a limp that persisted the rest of his life. He also had limited range of motion in his arms — he couldn’t raise them high enough to comb his hair; worse, from McCain’s perspective, the handicap thwarted his desire to return to the cockpit as a Navy pilot.

After years of recovery, McCain was rewarded with an assignment as the Navy’s liaison to the U.S. Senate, where he got his first taste of political power. He forged a number of bipartisan friendships, including a father-son relationship with Republican Sen. John Tower of Texas, who urged him to run for Congress, saying he could “do more good there” than in the Navy.

By then, McCain had divorced his first wife, Carol, after multiple admitted affairs on his part, and married Cindy Lou Hensley, the daughter of a wealthy Phoenix beer distributor. It was there, in the burgeoning desert of the Southwest, McCain finally rooted himself, working as public relations executive for his father-in-law’s liquor business.

In 1982, when a shot at an open House seat arose, he jumped at the opportunity. He knocked on some 15,000 doors in Arizona’s beastly summer heat and blanketed the local TV airwaves with an ad touting his military record that showed him hobbling on crutches soon after his release as a POW. He narrowly won the GOP primary and trounced his Democratic opponent.

After two terms in the House, McCain was elected in a 1986 landslide to replace retiring Sen. Barry Goldwater, another crusty, speak-his-mind Republican. McCain was reelected five times, the final time in 2016.

He kept a mostly low profile during his early years in Congress, voting a faithfully conservative line. In the 1990s, in a move with great symbolic and political resonance, he worked across the aisle with Kerry to end the U.S. trade embargo on Vietnam and renew diplomatic ties.

Perhaps his greatest notoriety, however, came as a member of the “Keating Five.”

In the late 1980s, Charles H. Keating Jr., the owner of Irvine-based Lincoln Savings & Loan, spread cash donations to five U.S. senators — including McCain — in hopes of thwarting a federal investigation into Lincoln’s questionable investments and lending practices.

After a lengthy court-like procedure, McCain was found guilty by the Senate Ethics Committee of showing “poor judgment” for twice meeting with regulators at Keating’s request. Although there was no sanction, McCain called the experience worse than anything he suffered as a war prisoner.

“The Vietnamese,” he said, “didn’t question my honor.”

The experience changed McCain in two ways. He became increasingly accessible to reporters, figuring the best path to political rehabilitation was openness and unvarnished authenticity. He also took up campaign finance reform, opposing leaders of his own party and working with Wisconsin’s Democratic Sen. Russ Feingold to pass legislation restricting the flow of unregulated campaign cash and limiting political advertising.

In January 2010, however, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down key aspects of the McCain-Feingold bill, ruling curbs on political spending were an unconstitutional infringement of free speech. “The worst decision of the United States Supreme Court in the 21st century,” McCain called it.

By then, McCain had established himself as a national figure, after two tries for the White House.

His 2000 bid was an upstart effort that pitted him against Texas Gov. Bush and most of the GOP establishment. McCain wrote off Iowa, where voters cast the first ballots in precinct caucuses, and camped out for more than a year in New Hampshire, staging more than 100 town halls.

His ask-me-anything style appealed to voters demanding accessibility and reporters who loved McCain’s freewheeling personality. (“My base,” he jokingly called the political press corps.)

McCain’s walloping of Bush in New Hampshire’s leadoff primary stamped him as a serious contender for the nomination. Bush supporters responded with a smear campaign, including false allegations that McCain fathered an African American child out of wedlock. That helped Bush prevail in South Carolina’s do-or-die primary, but opened a deep personal chasm; when McCain finally came around to endorsing Bush after the primaries, he likened it to swallowing a bitter pill.

If McCain’s 2000 run for president was mostly a joy ride aboard the aptly titled “Straight Talk Express,” his 2008 campaign was a slog. Though he began as the presumptive front-runner, his open disdain for Christian conservative leaders, promotion of campaign-finance reform and moderate position on immigration alienated much of the Republican base.

He quickly fell behind in polls and fundraising and retreated in desperation once more to New Hampshire, where his familiarity and another blitz of town halls helped lift him to victory and an eventual path to the GOP nomination.

McCain entered the general election as a distinct underdog against Obama. After eight years of Bush, voters were inevitably ready for change and, as the first African American to seriously vie for the White House, the Illinois senator was the living embodiment of new and different.

Charismatic and 25 years younger than McCain, Obama also capitalized by portraying his GOP rival as old and out of touch. McCain’s slow, diffident response at the onset of the Great Recession didn’t help.

Trying to shake up the contest, McCain gambled by choosing little-known Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin as his running mate. Her rocky performance left campaign aides publicly lamenting the selection, though McCain expressed no regrets until death began its approach.

Only then did he reveal his second thoughts, writing in his final memoir and stating in an HBO documentary that he was sorry he did not select his close friend, Connecticut Sen. Joseph Lieberman, a Democrat-turned-independent.

McCain said campaign advisors told him the move would outrage hard-core Republicans and cost him the election. “Sound advice,” he wrote. “But my gut told me to ignore it, and I wish I had.”

Palin issued a statement Saturday night on Twitter, calling McCain “an American original.”

“John never took the easy path in life — and through sacrifice and suffering he inspired others to serve something greater than self,” she wrote.

After losing to Obama, McCain returned to the Senate and became one of his harshest critics, especially on defense and foreign policy matters. He continued to break with Republicans when it suited him, most recently pushing President Trump for a tougher stance against Russia and repeatedly opposing efforts to repeal Obama’s signature achievement, the Affordable Care Act, without ensuring coverage for the millions of Americans it added to insurance rolls.

He never bothered reconciling with conservatives back home, who threw up vigorous primary challengers when McCain sought reelection in 2010 and 2016. Both times he shifted right, on immigration and other issues, before moving back closer to the middle once he fended off the intraparty challenge.

If there was a single motivation threaded through his career it was public service, said Tom Volgy, a University of Arizona political scientist and former Democratic mayor of Tucson who worked well with McCain despite their partisan differences.

“He wasn’t a poor guy who needed to get rich by being in Congress,” Volgy said. “He didn’t need to serve so long, or run again after losing for president.”

Although both his White House bids fell short, McCain seemed awed and genuinely grateful for the mere chance to vie for the nation’s highest office.

“This is the noblest experience in the world,” he told a firehouse crowd as he campaigned one night in 2000 in New Hampshire. “It’s marvelous, and I can’t tell you how uplifting it is. … I seize every moment, every moment I can, to be in this campaign.

“In my darkest days, long ago and far away, I never, ever believed that I would have this golden opportunity.”

UPDATES:

6:30 p.m. : This article was updated with reaction from McCain’s former vice presidential running mate, Sarah Palin

6:07 p.m.: This article was updated with reaction from President Trump and former President Obama.

This article was originally published at 5:25 p.m.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.