Column: This is Judge Aileen Cannon’s big gamble in the Trump classified records case

- Share via

As U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon entertains another far-fetched argument from Trump’s defense team in the classified documents prosecution, a recent report sheds considerable light on her vexing oversight of the case.

When Cannon was assigned to the case by lottery, the New York Times reported last week, two of her fellow judges urged the Trump appointee to transfer the case.

Those calls were extraordinary. New judges like Cannon might seek out the advice of colleagues on various questions, potentially including whether to take on such a difficult case early in their tenure. But for not one but two other sitting judges to urge a colleague to give up an assignment demonstrates severe concern within the Southern District of Florida.

The special counsel suggested he could seek the 11th Circuit’s intervention if the judge continues to prevent the trial from taking place before the election.

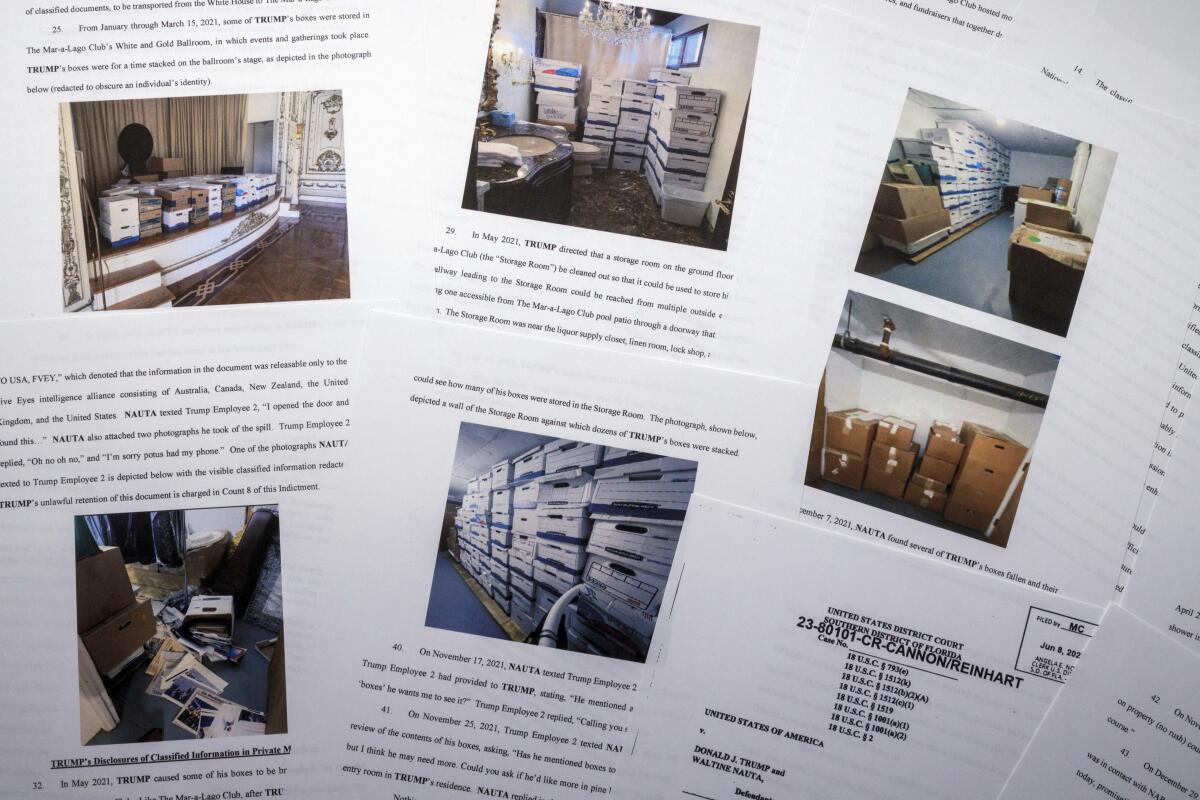

It’s not hard to understand why. Cannon’s assignment came six months after she spectacularly bungled a Trump lawsuit protesting the search for and seizure of the documents that would form the basis of the federal charges.

Cannon’s mischief-making in the civil case included her appointment of a special master to sift through the seized documents based on Trump’s claim of executive privilege. That shackled the Justice Department in an unprecedented fashion and drew criticism from legal experts of all ideological stripes.

It took two decisions excoriating Cannon by the conservative 11th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals to shut down her misadventure. Those two strikes against the judge arguably put her oversight of the case at real risk if she draws another rebuke from the appellate court.

The Florida jurist could impede the Department of Justice’s effort to hold the former president accountable for his handling of classified records in a few ways.

The first call to Cannon from an unidentified colleague reportedly offered face-saving reasons for her to give up the case. The judge pointed to logistical concerns such as the lack of a sensitive compartmented information facility, or SCIF, in Cannon’s Fort Pierce, Fla., courthouse. (In fact, Cannon’s retention of the case required a SCIF to be built there at considerable cost to taxpayers.)

But Cannon refused to take the hint. That was when the chief judge of the district, Cecilia M. Altonaga, reportedly stepped in to make a “more pointed” argument.

Altonaga gave Cannon the unvarnished facts, according to the report. She told the new judge that the prior debacle in the search warrant litigation made it “bad optics” for her to preside over the case. And since she was speaking as the district’s chief judge, the implication was that keeping the case would hurt not only Cannon but the entire district.

The report suggests a forceful appeal, close to a demand, from a chief judge to a novice with very little trial experience. The chief judge is the closest a federal judge gets to a boss. Moreover, Altonaga is an appointee of another Republican, George W. Bush, so Cannon had no reason to see her as a member of the enemy camp.

New federal judges to some extent have to leave society and old friendships behind, assuming a necessary distance from former colleagues that can be difficult. Their colleagues in the district typically become their closest confidants as well as a primary source of professional esteem. For those reasons, rebuffing one’s fellow jurists is the last thing most judges want to do.

And it hasn’t gone unnoticed. On the contrary, the New York Times reported that Cannon’s refusal of her colleagues’ entreaties “has spread among other federal judges and the people who know them.”

Cannon’s obduracy was a forewarning of her bizarre and almost ludicrously pro-Trump handling of the case. She has generally shown hostility to prosecutors, given extensive consideration to patently meritless defense motions, and studiously avoided issuing any rulings that could be appealed to the 11th Circuit and lead to her recusal. A case in point is Monday’s hearing of the defense’s dubious argument that special counsel Jack Smith’s appointment was unconstitutional.

The upshot is that what should have been the most cut and dried of the four criminal cases against Trump — a case in which his lawlessness is patent and uncomplicated — is highly unlikely to proceed to trial before the election.

The latest reporting on Cannon confirms that she is willing to invite the deep disrespect of the community that normally determines a judge’s professional standing. If Trump wins in November, she has every reason to expect the gamble to pay large rewards. If he loses, she has every reason to expect to go down with the ship. It’s a risk she appears determined to run.

Harry Litman is the host of the “Talking Feds” podcast and the Talking San Diego speaker series. @harrylitman

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.