Editorial: L.A. Metro is doomed if it can’t keep bus and train riders safe

- Share via

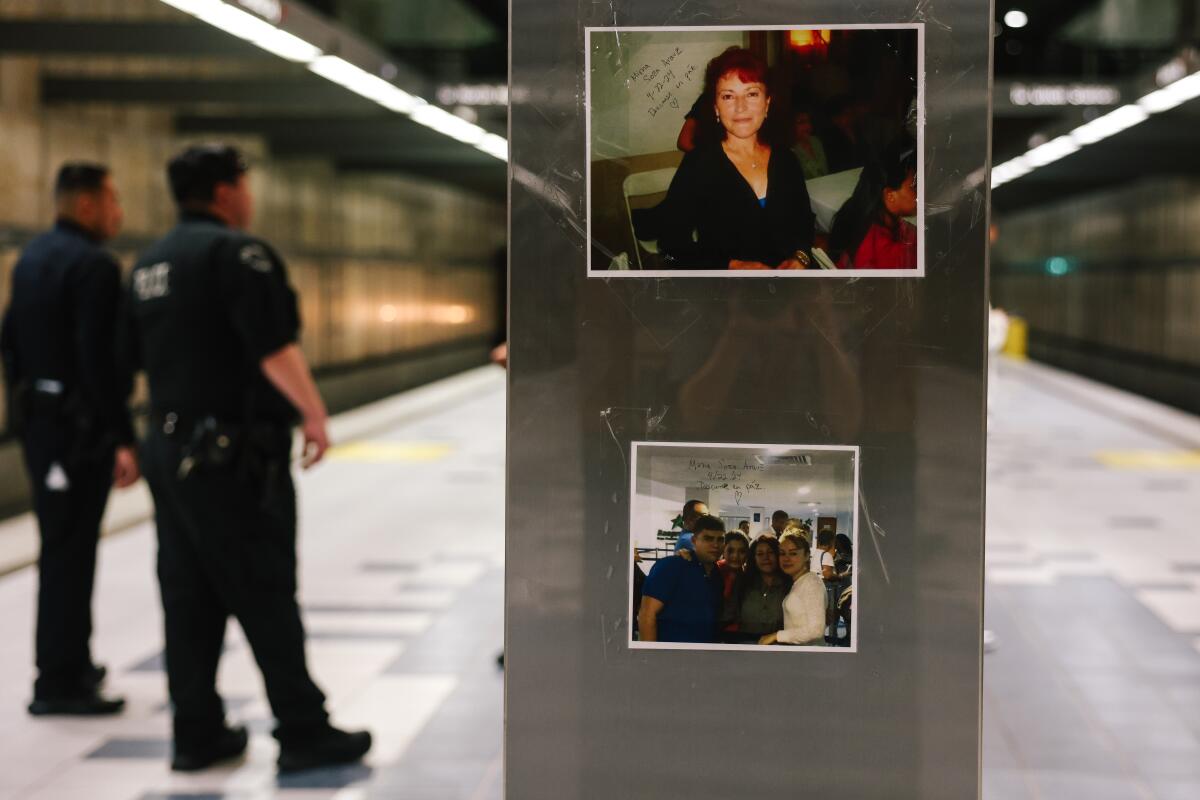

The recent violent attacks on the Metro system, including assaults on bus drivers and the fatal subway stabbing of Mirna Soza Arauz, 67, on her way home from work, present an existential threat to public transit in Los Angeles.

Taxpayers have invested billions of dollars in rail and bus expansions to fight climate change and make it easier for people to get around without driving themselves. Transit is supposed to be the backbone of L.A.’s “car-free” Olympics in 2028. But if people do not feel safe riding the buses and trains, the system will get stuck in a doom spiral and never gain the ridership needed to help reduce traffic and air pollution.

Disorder, rising crime and declining confidence not only pose an existential crisis to the Metro system but also to the region’s climate, sustainability and livability goals.

It’s not just passengers who are afraid. There were 160 assaults on public transit operators in 2023, a significant increase from 2019, and one operator was stabbed last month in Willowbrook. Metro declared an emergency, allowing it to fast-track installation of fully enclosed protective barriers for bus drivers, though they still staged a sick-out Friday to protest unsafe working conditions.

Metro leaders have to commit to major changes to keep the system safe and viable. One of the ideas that agency officials are discussing is creating an in-house transit police department, which should come up for a vote by Metro’s governing board in the next month or two. It’s worth considering as part of a necessary public safety overhaul.

Buses aren’t safer because their rubber tires act like crime-fighting vigilantes. Most likely they’re safer because more people use them.

The current arrangement is not working well. For 30 years Metro has largely outsourced security to law enforcement agencies. At the moment, the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department and the Los Angeles and Long Beach police departments split responsibility, making accountability difficult. Some of the agencies patrol the system using officers on overtime shifts, which means they have less day-to-day familiarity with the system and riders. Officers are responsible for enforcing the penal code and responding to crime, which is important and necessary, but there is real debate about what role law enforcement should have on the system.

The vast majority of safety concerns cited by riders are about comfort and cleanliness, as well as code of conduct violations. Homeless people sleeping on the trains and buses. People experiencing mental health crises. Fare evasion. Drug use or people passed out from intoxication. Passengers playing loud music. These are prevalent throughout the system but not consistently addressed, which feeds into the sense of disorder.

It makes no sense to keep investing so much more in measures that haven’t kept transit safe than in ambassadors and other services endorsed by riders.

The recent spate of violence shows there are major gaps in communication and prevention. For example, the man suspected of stabbing Soza Arauz had been banned from Metro previously for assaulting a passenger. But there is no regular communication among the courts, law enforcement and Metro staff to flag people with stay-away orders. It’s a serious problem if a relatively small number of offenders are allowed to continually harass passengers.

Last year Metro hired 48 additional in-house security staffers specifically to ride the buses on routes that have higher-than-average crime and safety concerns. Officers with contracted law enforcement agencies patrol bus stops at the beginning and the end of route, but don’t typically stay on problematic bus lines. Metro officials want to hire more security personnel to increase the number of bus-riding teams, which is a good idea to improve conditions for drivers and passengers.

Reaction to two brutal assaults in Venice demonstrates how emotion and politics twist the truth in crime discussion. Los Angeles leaders must do better.

Metro also launched a transit ambassador program to make riders feel safer. Since March 2023, there have been 300 unarmed and trained ambassadors riding the trains and buses providing customer assistance and calling for security and social services teams as needed. In a survey of riders, 63% said that seeing an ambassador made them feel safer. And the agency has contracted with homeless outreach teams and sought mental health training so staff can intervene when someone is in crisis.

Like transit systems across the nation, Metro saw a big drop in ridership during the pandemic followed by an increase in safety concerns as people struggling with homelessness, drug addiction and mental illness sought refuge on buses and trains.

While the last few years have been especially challenging, Metro has had a public safety perception problem for a long time. In a 2016 survey, almost 30% of past riders said they left the system because they did not feel safe. Respondents said security and safety were bigger deterrents to using public transit than the speed and reliability of buses and trains.

This is the moment for Metro to finally develop a comprehensive approach to safety — and put it in place quickly. That means having consistent personnel, whether sworn police officers, security guards or other unarmed staff, who patrol the buses and trains every day, develop relationships with operators and commuters and are empowered to enforce the laws and the code of conduct. Riders deserve safer bus and rail service. And Metro is doomed without it.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.