Russell Banks found the elusive heart of Trumpism in a fictional New York town

- Share via

Book Review

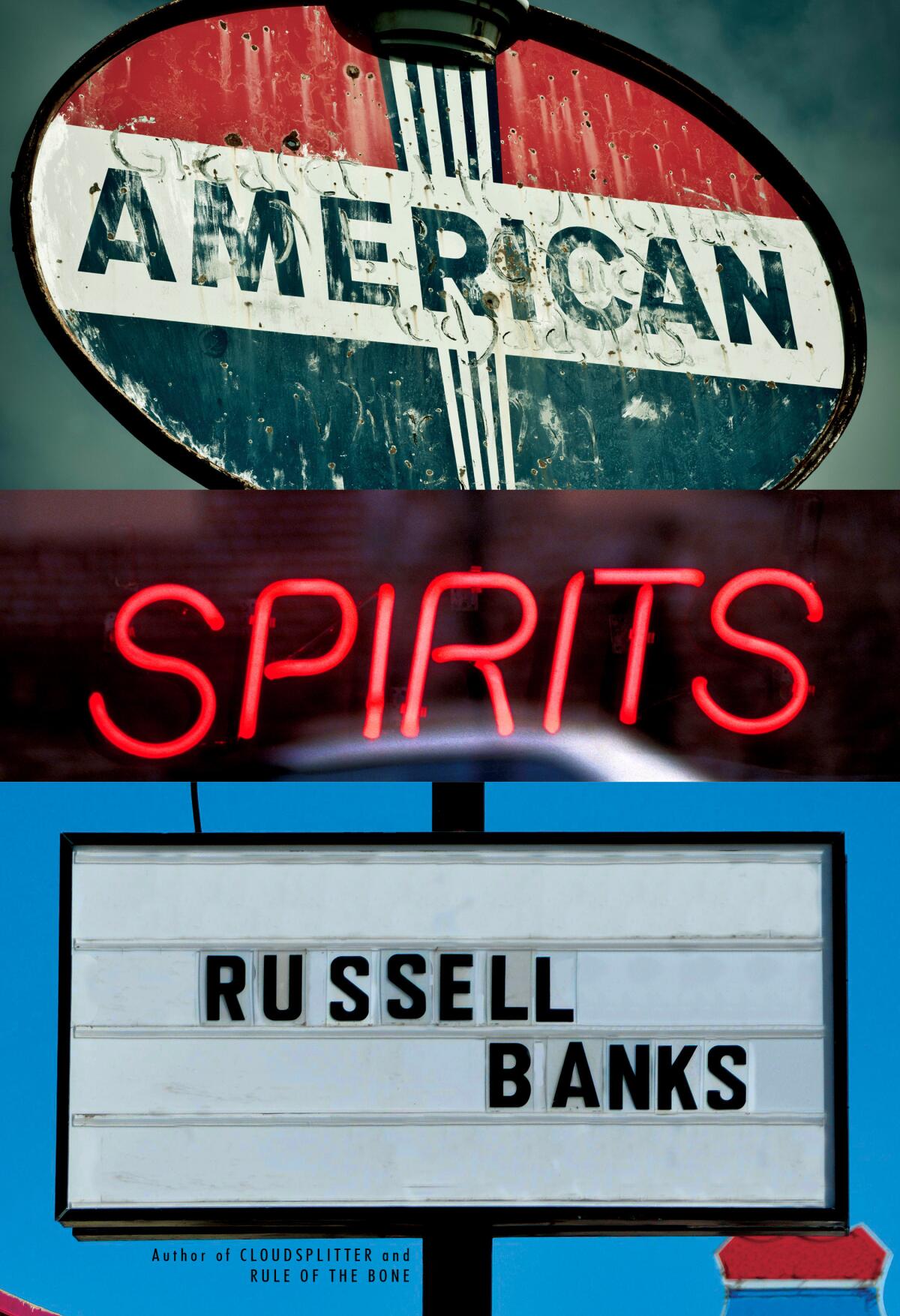

American Spirits: Stories

By Russell Banks

Knopf: 240 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

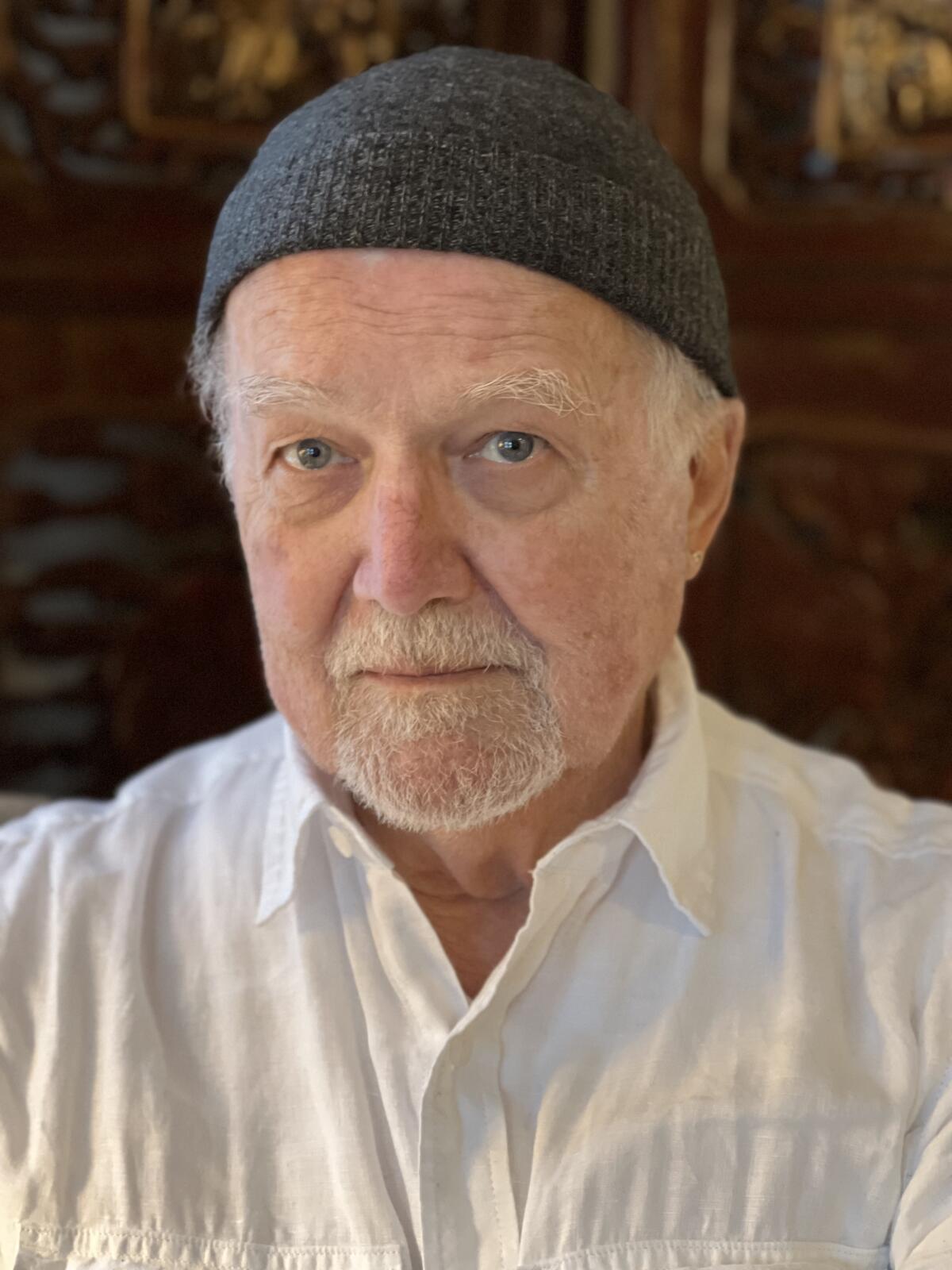

For years now, writers have tried various ways to capture the heart of Trumpism. Attend a rally. Convene a focus group. Find a Panera Bread in exurban Ohio. Russell Banks, in his first book published since his death in January 2023, seemed to figure that he need look no further than his own bibliography.

In a triptych of linked stories, “American Spirits,” Banks imagines a rural stretch of upstate New York evoking the rough-hewn settings of his bleak novels including “Affliction.” He doesn’t unearth surprising insights, but newness is beside the point. Rather, he wants to stress that the core of Trumpism — rapaciousness, ego, territorialism, a will to violence — is foundational to American society.

The setting for all three stories is Sam Dent, a fictional New York burg Banks introduced in earlier work. It’s a symbol of the country’s great striving middle: “Sam Dent is not the kind of town where a few people make a killing and the rest are on welfare,” he writes. “Here everyone gets by, just barely.”

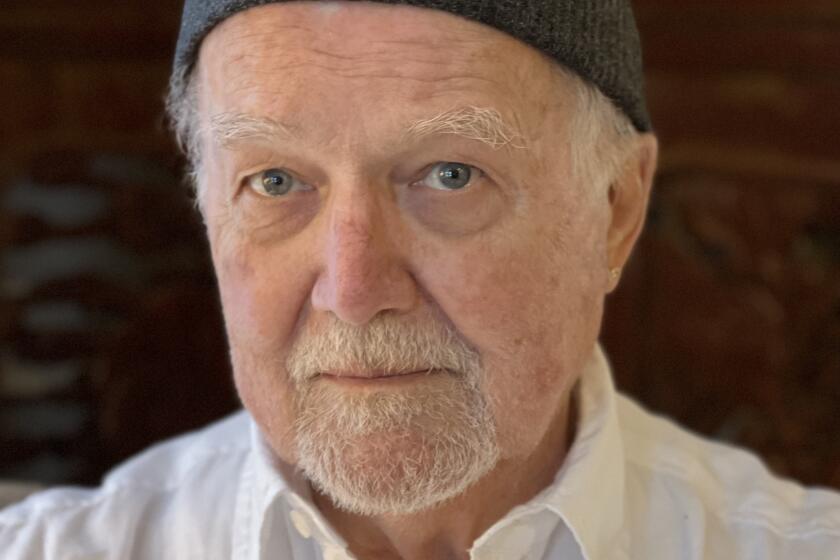

Russell Banks, who has died at age 82, carried on the legacy of great American novelists probing big themes through the small lives of heroic underdogs.

In the opening story, “Nowhere Man,” the person just getting by is Doug, a laborer and sport hunter who sold off a parcel of land he inherited. The man he sold to, Yuri Zingerman, has turned the land into a camp for paramilitary and survivalist training. It’s a Chekhov’s gun story, just with AR-15s.

Doug, an unnamed “we” informs us, was promised the right to hunt on the land after selling it. But tensions escalate when Yuri reneges on that promise. After they squabble in a bar, Yuri pins Doug down in a flash and threatens him, a scene suffused with working-man exploitation and might-makes-right amorality: “Zingerman’s ability to do it so quickly that Doug couldn’t see it happening until it was already over and done. It mystified Doug.” The endgame here is inevitable, but Banks artfully captures the precariousness of existence before existence turns tragic, the way feelings of masculinity get tangled up in that precarity, and how macho posturing only makes it worse.

The middle story, “Homeschooling,” is more ambiguous, centered on a young conservative couple who aren’t sure what to make of their new neighbors, a white lesbian couple with four adopted Black children. The neighbors’ live-and-let-live approach is challenged when one child, then another, arrives on their doorstep claiming starvation and abuse by their adoptive moms.

Over five years, I read 1,001 novels to hear the voices that fill this country. These books showed me that the places of American fiction can’t be divided into blue or red states.

The fate of the children is one horror, but the inability to comprehend difference is crushing in its own way. The narrator suggests that Sam Dent is consumed with a viral rage straight out of “The Lottery”: “It was almost as if folks had decided that they were tired of being tolerant of the presence of the Weber women and their four Black children and were no longer obliged to treat them as legitimate members of the community.”

An unnamed narrator tells the stories of “American Spirits,” giving them a glint of passed-on legends, folklore or cautionary tales — “Winesburg, Ohio” with all the magic flayed off it. The narrator informs the reader that Sam Dent’s namesake made his fortune from land purchased through fraud, making the town a place of “wartime plunder and misappropriation and forgery and outright theft, self-aggrandizement and egoism and greed.” The MAGA hats that characters wear proudly throughout the book at once crystallize the deliberate ignorance of that past and underscore the injustice they perpetuate in the name of red-blooded patriotism.

Irony is on clearest display in the closing story, “Kidnapped,” in which a retired couple is taken hostage by French Canadian drug dealers, ransomed for the bad choices of their daughter and special-needs grandson. Banks gives this dynamic over-the-top treatment in some ways — there’s ample gunplay, and a TV set blares “America’s Got Talent.” One of the dealers scoffs at Trumpian simplicity: “You all worried about Mexico and building Trump’s wall, and meanwhile anybody who wants can walk across from Canada.” But Banks puts forth a more subtle undercurrent here, that all this lurid violence stems from a failure to see our shortcomings clearly, and an unwillingness to call out the (macho, bigoted) forces that manipulate it.

That sensibility is what we lost when Banks died last year. Violence woven with politics and human foible was his hallmark, showcased in contemporary classics like “Continental Drift,” in which a New England working man gets roped into human trafficking, or “Cloudsplitter,” a historical novel about John Brown’s slave revolt, and even up through 2022’s “The Magic Kingdom,” in which all-American cultishness wrecks a man and a community simultaneously.

Because Banks’ concern was always with the ways Americans delude themselves in the name of freedom or righteousness, he never ran out of material. “American Spirits” isn’t the finest example of his talents, but it’s a user-friendly introduction to his sensibility, fit for an election year when delusion is part of the narrative. In Banks’ parcel of America, residents try to escape the past, but the past always has a way of getting back at us. As he writes: “In the end, somebody had to pay, because in the end everybody has to pay.”

Mark Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.