Opinion: The border crisis factor no one talks about: American guns

- Share via

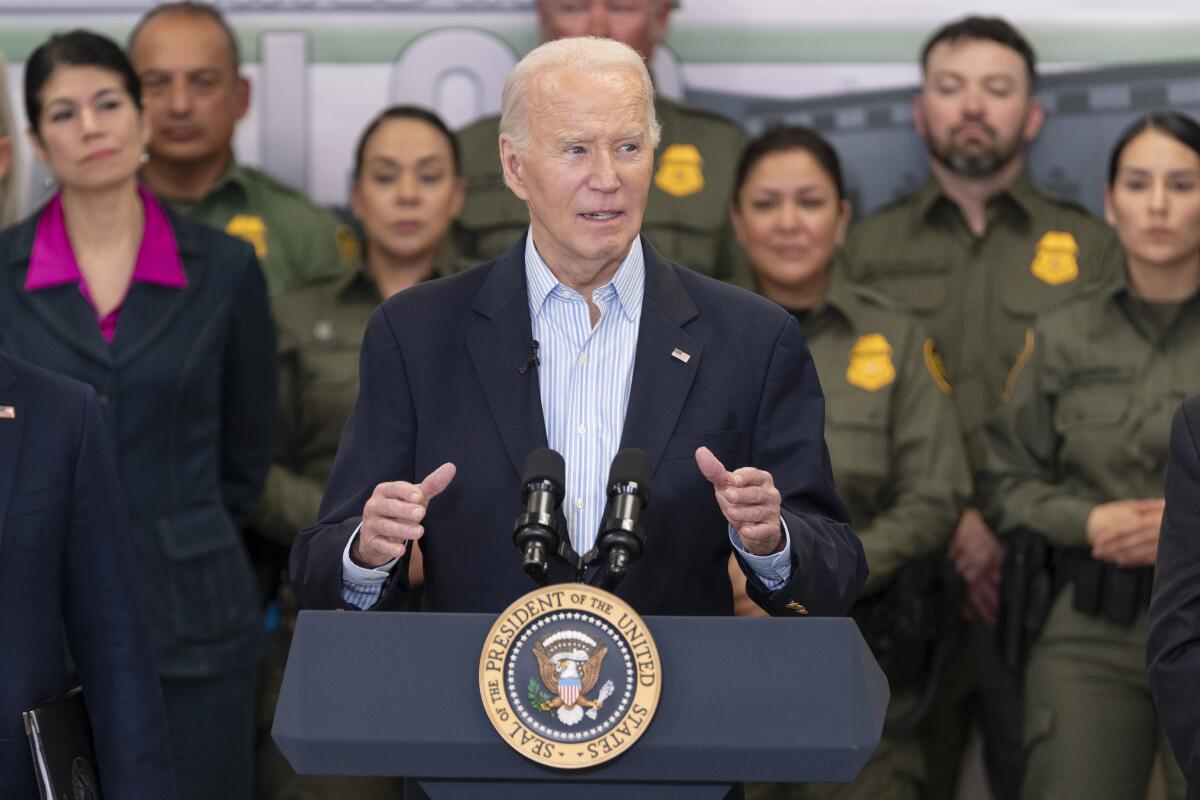

When President Biden and former President Trump visited Texas at the end of February, each spoke about migration and border security. Biden called for restricting asylum. Trump engaged in fear-mongering, blaming migrants for crime. But neither mentioned one of the main reasons the border has drawn so many migrants and asylum seekers — the flow of guns from the U.S. into Mexico.

This link between our guns and the people who seek safety at the border is particularly clear in Texas. Gov. Greg Abbott’s hard-line approach to stopping migrants from crossing completely ignores the state’s role as a main source of weapons for criminal groups and violence in Mexico, which is a result of its loose gun regulations. It’s no wonder that Mexicans are the largest national group among the hundreds of thousands who try to cross the U.S. southern border each year.

Blocking asylum seeker at the border would violate America’s international obligations and fuel false narratives about an immigration crisis.

Since I began volunteering in 2015 at a migrant aid clinic in Nogales, Mexico, I have met the men, women and children who make up these statistics. Various presidents and Congresses have handed down a hodgepodge of policies intended to solve the perpetual crisis on the border, but the reasons people try to escape Mexico and the difficulties they encounter on their journeys have not changed in any meaningful way.

At the clinic, mothers and fathers told us why they had to flee. Somebody’s brother was murdered. Somebody’s cousin was kidnapped. Somebody else could no longer pay extortion fees. These migrants were fleeing insecurity rather than poverty, although the two often overlapped. Criminal violence is a problem throughout Mexico. In 2023, more than 110,000 Mexicans were officially listed as disappeared. Close to 90% of all crimes are never reported and 9 in 10 homicides go unpunished. In some parts of the country, law enforcement works with organized crime groups. The families I met did not have an option to go to the police. They packed what they could carry, hoping to find safety once they crossed the border.

Illicit imports of the opioid drug responsible for a fatal overdose crisis largely come from Mexico. But U.S. citizens bring most of it through legal ports of entry.

It’s not only people that are affected by the proliferation of guns. The criminal organizations forcing families to flee are often also running the Mexican drug trade. When fentanyl is smuggled across the border, usually through ports of entry and often by U.S. citizens, it wreaks havoc in our communities. But the drugs would not be coming north in such large numbers if not for our guns flowing south.

One reason that American guns have such an outsized role in Mexican crime is because unlike the United States, Mexico has very strict gun laws. There are only two gun stores in the country where vetted citizens can purchase a limited number of relatively small-caliber weapons. But in Texas and Arizona, states that share the longest border with Mexico, there are more than 7,000 federally licensed gun dealers and pawnbrokers. And while the majority of guns recovered in crime scenes around Mexico are traced to stores in these two states, some come from as far as Arkansas, Florida and Massachusetts. It is estimated that between 200,000 and more than half a million firearms purchased in gun stores, at gun shows or through private sales in the United States are trafficked south across the border.

Five years after his last visit, an artist returned to the U.S.-Mexico border wall to see what has changed. For a graphic op-ed, he drew what he saw.

In 2021, the Mexican government sued U.S. gunmakers, including Colt, Smith & Wesson and Barrett, for their “overall destabilizing effect on Mexican society.” A year later, it filed another lawsuit against gun dealers in Arizona who sold firearms that routinely ended up in the hands of organized crime groups in Mexico. Both cases are still winding through the courts.

The 2005 Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act shields U.S. gun makers and gun dealers from civil liability for injuries to people in the United States. But the Mexican government argues that this exemption does not apply to Mexico. Just as U.S. companies “may not dump toxic waste or other pollutants to poison Mexicans across the border,” it insists in the lawsuit, “they may not send their weapons of war into the hands of the cartels, causing repeated and grievous harm, and then claim immunity from accountability.” The Mexican government shares responsibility for failing to protect its citizens. But its failure to uphold the rule of law in part results from the firepower of organized crime groups, armed with American-made military-style weapons.

It is a vicious circle of violence. Without the river of firearms flowing south, the northbound flow of drugs would diminish. Without the threat of gun violence, many families would not risk their lives trying to reach and cross the border, seeking safety for themselves and for their children. The exodus of people from Mexico and other countries in the region and the injuries we treat at the clinic are in large part the result of America’s refusal to control the gun industry, allowing it to wound communities on both sides of the wall and perpetuate the never-ending border crisis.

Ieva Jusionyte is an associate professor of international security and anthropology at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University. Her new book is “Exit Wounds: How America’s Guns Fuel Violence Across the Border.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.