Opinion: Is Narendra Modi’s India still a democracy?

- Share via

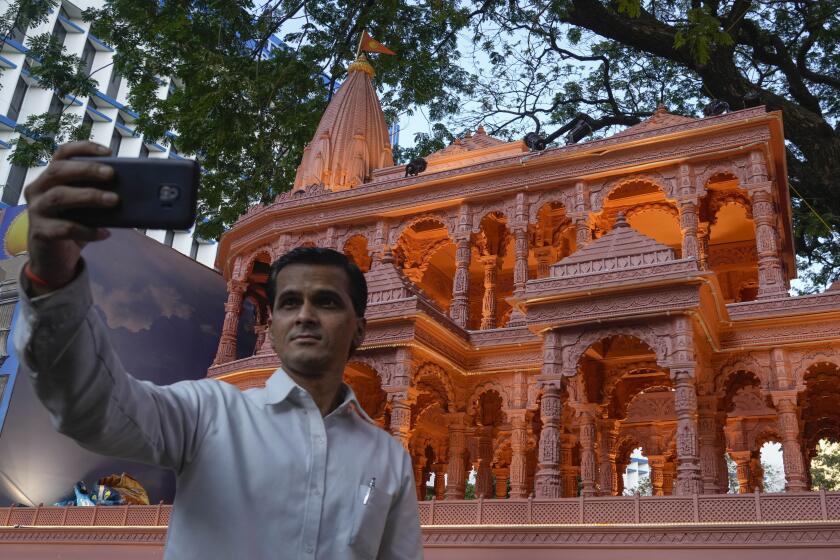

When Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi led the consecration of a vast new Hindu temple atop the ruins of a demolished Muslim mosque in the town of Ayodhya in northern India last week, it showed how far he will go to secure his reelection this year.

Not that stoking religious strife is a new tactic for the 73-year-old Modi. He rode to power, and clings to it now, on the back of militant Hindu nationalism and the menace of anti-Muslim violence.

In 2005, Modi, then the top official in the Indian state of Gujarat, became the first and only person ever barred from entering the United States under a little known immigration law that makes foreign officials ineligible for visas if they are responsible for “particularly severe violations of religious freedom.”

The temple will fulfill a longtime Hindu nationalist pledge and is expected to resonate with Hindu voters as Prime Minister Narendra Modi faces an election.

U.S. officials had determined that Modi stood by during Hindu riots that killed more than 1,000 Muslims in Gujarat state in 2002. The visa ban was lifted only when he became prime minister in 2014.

Today Modi’s brand of militant Hindu supremacy has replaced political pluralism as India’s dominant ideology, threatening the nation’s status as a secular republic.

As a foreign correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, I saw the beginnings of India’s anti-democratic slide on a sunny day in December 1992, on contested ground in Ayodhya.

Thousands of Hindu pilgrims, white-bearded priests, dhoti-clad holy men and other devotees who had gathered for a political rally suddenly stormed the historic Babri mosque, built in the 16th century by Babur, the first Mughal emperor, on the site of the supposed birthplace of the Hindu deity Ram.

A morning newspaper headline called it the “Temple of Doom,” but when I arrived here Sunday morning at the most controversial religious site in all India, Ayodhya looked more like a Hindu Woodstock.

The Hindu mob tore the mosque apart, brick by brick, with pikes, pickaxes and their bare hands. They pulled down guard towers with grappling hooks and climbed barefoot over barbed wire barricades. Foreign journalists were chased and clubbed. I was whacked with bamboo and hit with a brick.

The destruction of the mosque set off some of its worst religious pogroms in India since independence in 1947. Entire Muslim neighborhoods were torched and families slaughtered. Anti-Hindu riots broke out in response in Pakistan and Bangladesh, India’s Muslim neighbors. A Newsweek cover famously warned of “Holy War” on the subcontinent; its rival Time deemed the communal violence an “Unholy War.”

Three-plus decades later, much of India came to a standstill Jan. 22 to watch as Modi consecrated Ram Mandir, a richly decorated $220-million temple built over the destroyed Babri mosque. In many Indian states, it was a public holiday. Stock markets and most schools and offices were closed. Government offices shut for half a day.

Nonstop TV coverage showed the prime minister placing a lotus flower by the jet-black Ram idol in the temple’s inner sanctum, prostrating himself before it and all but declaring Hinduism a state religion. An Indian air force helicopter dropped flower petals outside, priests blew conches and chanted, but Modi was the star.

Rhetoric about democracy papered over policies advanced by Narendra Modi and his party that discriminate against India’s Muslims and limit freedom of speech and the press.

“Ram is the faith of India, the foundation of India,” he told a rapt crowd in Hindi, according to the Times of India. “Ram is the thought of India, Ram is the law of India. … Ram is the policy [of India].”

Modi has become the “high priest of Hinduism,” the prime minister’s biographer, Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, told the Indian website Rediff.com after the ceremony. “We are very close to becom[ing] a theocratic state.”

Such a notion would be anathema to India’s once revered founding leaders, Mohandas K. Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Government should embrace all religions, not impose one over the others, they argued. Those secular values are enshrined in the Indian constitution.

But secularism has waned as Modi’s right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party has steadily gained power by blurring the lines between Hinduism and the state. Muslims have their own countries, Modi’s supporters argue. Why shouldn’t we?

Here’s why: Although 80% of India’s 1.4 billion people identify as Hindu, 200 million Muslims and tens of millions of Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and others do not. Human rights groups say non-Hindus are increasingly treated like second-class citizens.

Rahul Gandhi says India’s right-wing government is dividing the country along religious lines. Followers hope his cross-country march can save democracy.

Modi’s “government has adopted laws and policies that discriminate against religious minorities, especially Muslims,” Human Rights Watch warns on its website. “This … has emboldened Hindu nationalist groups to target members of minority communities or civil society groups with impunity.”

In the days since Modi presided over the the temple rituals in Ayodhya, Hindu mobs rampaged in several cities and towns. News reports tallied the damage: Muslim-owned shops destroyed in Mumbai, Muslim students beaten in Pune, a Muslim graveyard burned in Bihar and so on.

Modi doesn’t need to inflame anti-Muslim prejudice to win reelection. He has a 76% approval rating in the latest polls and is on track to become the first Indian prime minister since Nehru to win three consecutive terms.

But the danger of more clashes is growing.

Hindu nationalists have filed lawsuits to remove hundreds of Mughal-era mosques that they claim were erected over other ancient Hindu temples. Their top targets include a mosque supposedly built over the birthplace of Krishna, the Hindu god of compassion, and a second in Varanasi, said to be the sacred abode of Shiva, Hindu god of destruction.

“People will always remember this date, this moment,” Modi said in Ayodhya last week, hailing the start of a “new era.”

I fear he may be right.

Bob Drogin is a former reporter and editor for the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.