Opinion: Thirty years after the Northridge earthquake, I still think about a hero I met that day

- Share via

Californians all have our earthquake stories.

Mine is of a man I’ve looked for since I missed the Northridge quake three decades ago, on Jan. 17, 1994, a bus driver we think was named Reggie. Reggie was a model of altruism that day. I wonder if he’s told this story, if he knows that my friends and I think about him every year around this time.

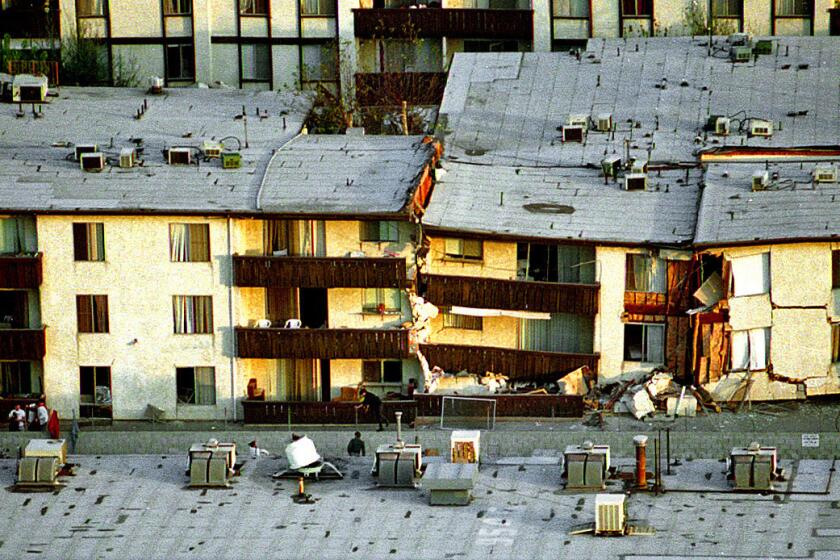

Missing the quake likely saved my life. The fraternity house I lived in was a mere block from the Northridge Meadows, the apartment building that pancaked along Reseda Boulevard, killing 16. The ceiling above my bed collapsed into a million shards where my head would have been, but I wouldn’t learn that until much later.

I woke up on the morning of the 17th in a hotel outside of Reno. I was with a group of fellow Cal State Northridge students on a ski trip to Lake Tahoe. My friend Dave was pounding on my door. “Turn on the TV,” he said and then he was in my room, turning on the TV himself. It was 6:30 in the morning. On the screen we saw an aerial view of destroyed buildings, cratered streets, a bifurcated highway and then CSUN’s 2-year-old C-lot parking structure, which was bent hideously, like a broken leg. Many of the people on the ski trip had parked their cars in that structure. They’d never get them back.

The camera panned out. The San Fernando Valley was shrouded in smoke and flame. Somewhere out there was my family. My sisters in Sherman Oaks, my brother in Encino. Were they alive? Did they even know I was out of town?

I tried calling.

Nothing.

People are much more important than kits. People will help each other when the power is out or they are thirsty. And people will help a community rebuild and keep Southern California a place we all want to live after a major quake.

We were instructed to gather in a parking lot outside the hotel. A blond man from the tour company that had been contracted to coordinate our trip to Lake Tahoe stood with a bullhorn. I remember him looking like James Spader. “Listen,” he said, “under no circumstances will we be driving these buses back to Northridge today or anytime soon. You all have lift tickets and hotel rooms, so just enjoy your vacation, OK? That’s it.”

We were supposed to just … ski?

James Spader set down the bullhorn.

Reggie, an African American man who had driven one of the buses to Tahoe, picked it up.

“I’ve got a wife and kid in L.A.,” he said without preamble. “I can’t get through to them.” The crowd went silent. None of us had gotten through to anyone yet. “They can fire me, but if you want to ski, get on another bus, because this bus?” Reggie pointed at his idling coach. “This bus is headed home!” Dozens of us piled onto the bus. Plenty of others stayed behind.

When we settled into our seats, Reggie stood up at the front. “We’re in this together now,” he said. “I’m going to get all of you home, no matter where you live.” He paused. “I know you’re probably scared. I’m scared, too. So let’s share phones, see if we can get through to our people, and we’ll stop every now and then to use pay phones. I’ve got a radio up here. I hear something, I’ll pass it on. But my intention is to get home as fast as possible. Cool?”

Cool.

The Northridge earthquake

For the next 12 hours, we wound down the length of California on two-lane roads and interstates. We shared snack food. We lined up for pay phones at rest stops, but nothing was getting through. We whispered our fears. We play-acted as adults when all we wanted was our mothers. And all along, Reggie drove. “Everyone all right?” he’d ask every 15 minutes or so. “Just a few more hours to go.” It was always a few more hours.

We finally reached the Valley late that night. I’ve tried to map the route Reggie must have taken. It makes no sense to me now how he managed to get us onto the 101 South, but there we were, exiting on Tampa, rolling over broken, pitch-dark streets, fires burning in the distance, before coming to a gulch of shattered pavement a few feet wide and filled with water.

Reggie stopped the bus. He turned and looked at us. “Well,” he said, “how about we see what this bus can do?” He told everyone to hang on, backed that bus up a block, gave a little chuckle — and floored it! We sailed right over that gulch.

A drying Salton Sea may be helping delay the next Big One, but that could result in a more powerful quake when it does strike.

From there, Reggie did exactly what he said he would do: He took us home, pulling up in front of our wrecked dorms, our tilting apartment buildings, our fraternity and sorority houses, all soon to be tagged red, yellow or green to indicate their safety. When we finally reached the frat house I lived in, I could make out the glow of sirens down the block. They were looking for survivors they would not find, but I didn’t know that then.

Ten of us piled off the bus. I don’t remember if we shook Reggie’s hand. We must have thanked him. But the truth is that I don’t know anymore, because by the time I got off that bus I was in a full panic. Were my siblings alive? My girlfriend? My friends? Each of us walked off that bus into an unknown future, dazed by the trip, lost in what the light might reveal.

In the end, I lost no one.

We didn’t talk about Reggie right away. It would be months, actually.

And then someone would say: How crazy was that bus ride?

And we’d all agree: Crazy.

Did he really jump that gulch?

He really did.

Crazy. Dude was a hero.

He was. He is. I hope he knows.

Tod Goldberg is an author, most recently of “Gangsters Don’t Die.” He directs the Low-Residency MFA Program in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts at UC Riverside.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.