- Share via

JERUSALEM — Advent has crept in quietly this year in the Holy Land. It has been stripped away from the usual trappings of Christmas, which normally are impossible to resist either here in Jerusalem or anywhere else in the world. It might please the Advent purists if the reason for the somber mood were not the unutterably awful events from Oct. 7 in Israel and every day since in Gaza.

In some traditions, the great Advent themes are death, judgment, heaven and hell. This has become too grim for some churches, but for us in Palestine, we feel we have actually been living in these themes for the past weeks. According to this Advent pattern, the joy of Christmas bursts into our contemplation of these “Last Things” and envelops them with the love and peace of the Incarnation. In the Holy Land, we are going to struggle to get to the joyous part.

Palestinian Christians were killed in an Israeli airstrike at St. Porphyrius Greek Orthodox Church in Gaza. We pray for peace but fear our presence may disappear altogether.

On any other Christmas this would not be a problem. To be in the Basilica of the Nativity in the Chapel of St. George for a service of lessons and carols on Christmas Eve is one of the most beautiful experiences imaginable. We gather together singing “O Little Town of Bethlehem” in that very place; normally, it is not difficult to feel the joy of that moment. When our voices raise, “Sing through all Jerusalem: Christ is born in Bethlehem” in our cathedral in the Holy City, we feel a tingle of Christmas excitement.

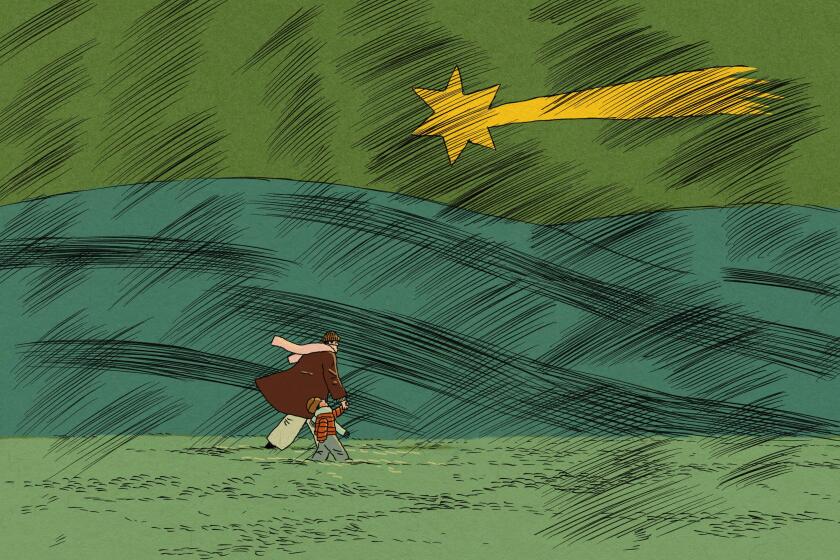

But this year it is different. This year our land is grieving and in deep pain, and we are fearful for what the future holds. The daily bombing of Gaza and the terrible death toll of children, women and men has cast a very dark shadow. The atrocities of Oct. 7 at the Nova music festival and the nightmares that played out in Kibbutz Be’eri leave a stain of deep pain on the Holy Land and its peoples. It is as if a gray pall hangs over the cities and towns of these lands that were once made holy for people of faith by the God-revealing events that took place in them throughout history. These events are not only Jesus’ birth, life, death and resurrection but also include the prophets who foretold and the patriarchs and matriarchs who created a foundation for the whole history of salvation, which culminated in Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem.

I’ve drifted away from the church. So when my kids asked me why people celebrate Jesus’ birthday, I struggled for an answer — until the gospel of Luke showed me the way.

With our world tarnished by such suffering, how can we celebrate this year with the usual Christmas joy? The heads of the churches in Jerusalem rightly canceled the festivities and parties in which we usually indulge. Instead, we have tried to focus on the spiritual core of Advent and its attentive waiting for the promised Messiah, but we have been weeping and raging, and it has been hard to focus on hope when despair knocks at our door.

But wait, we should revisit this familiar story of the babe born in a stable in the “little town.” Christmas categorically is not just for the children: new toys, Christmas lights, gut-busting meals and “little lord Jesus asleep on the hay.” This is actually a “history-story” that can bear the weight of the world’s grief and pain, as it can also bear the weight of whatever sadness in our personal lives we live with today. It can bear the weight because the story itself is soaked in trauma and framed by people and events every bit as fearful as our own.

With Jewish and Palestinian relatives, I’ve learned there isn’t a clear and exciting enough symbol for a two-state solution.

Herod’s most notorious act was to massacre the innocent children of Bethlehem to avoid a rival child growing up to displace him. The holy family fled as refugees to Egypt. Yes, this is a story with all the turmoil, pain and jeopardy that we have been feeling these past months. The story of the birth of the Messiah can contain our darkest feelings of fear, anger and sadness, because it is drenched in them too.

It can bear the weight because Jesus, born in Bethlehem, is the presence of God in the midst of the realities of life and not some Disney fantasy of life as we might wish it could be. Jesus came as the prince of peace, in marked contrast to the Pax Romana established by Emperor Augustus. Jesus came as Immanuel, “God with us” in a world that believed that God was distant and detached from the muck and grime of everyday life. Our friend, Rev. Munther Isaac, a Lutheran pastor in Bethlehem, has powerfully proposed the idea that Jesus is born this Christmas not in a stable in Bethlehem, but among the wreckage of war in Gaza. “God is under the rubble,” he has proclaimed.

Imagining possible futures beyond Israel’s Jewish supremacy is a political act for me, rooted in my people’s history.

The Christmas story tells us that God is with us, our comfort and our strength whatever trials and tragedies befall us, contending with us against all that is evil.

This is a message for the people of Gaza in the depths of their suffering. It is for the families and friends of the hostages in Israel. It is for the Palestinian villagers fearing for their safety and their livelihoods in the West Bank. It is for the victims of antisemitism and Islamophobia everywhere in the world. It is a warning to those who exercise their power to oppress others, and it is a warning to those whose violence causes death and suffering.

The Christmas message of hope and peace defies all of those former things. It is down to each of us to discover how the message of Christmas will be lived out in our lives. Christmas joy may feel a long way off in the Holy Land, but even a distant murmur of it can make the difference our hearts crave.

The Very Revd Canon Richard Sewell is dean of St. George’s College Jerusalem. This essay was adapted from a sermon that will be delivered on Dec. 25.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.