Opinion: A Texas case shows how cruel and illusory the latest abortion-ban exceptions can be

- Share via

A historic drama playing out in Texas ended Tuesday when the Texas Supreme Court held that Kate Cox, a woman 20 weeks pregnant with a fetus with trisomy 18, an almost always fatal abnormality, could not legally end her pregnancy in her home state.

Cox had taken the rare step of petitioning for a court-ordered abortion. She succeeded in the lower court, prompting Texas Atty. Gen. Ken Paxton to appeal and threaten local hospitals and Cox’s doctor with prosecution if she got the procedure. The Texas Supreme Court quickly handed down its ruling: State law did not make an exception for fatal fetal abnormalities and Cox was not near enough to death or permanent impairment of a major bodily function to qualify for an exemption. She traveled out of state to terminate her pregnancy.

The Supreme Court will decide whether to put stricter limits on abortion pills that are now the most common method for ending early pregnancies.

Cox’s loss in court illustrates the confusing, contentious state of abortion law since Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned Roe vs. Wade in 2022. (The Supreme Court’s announcement Wednesday that it would take up challenges to medication abortion is another such indicator.) Abortion-ban exceptions are particularly fraught. Their complexities and the current antiabortion playbook add up to an extraordinary reality: Present-day abortion-ban exceptions will fail to protect patient health, no matter how Americans may interpret them or the intentions of the legislators who passed them.

When states began criminalizing abortion in the 19th century, almost every ban had an exception for the life of the patient. In the 1960s, legislators introduced additional exceptions: for sexual assault, incest, fetal disability and certain health risks.

Even then, exceptions proved to be contentious and unworkable. Early on, before the 1940s and 1950s, prosecutions were rare unless a patient died. In practice, that gave physicians discretion to determine when there was a real threat to patients’ lives. But later, prosecutors began cracking down on a larger group of abortion providers. Hospitals and physicians responded by setting a high bar for legal abortion to shield themselves from criminal liability. Patients without money or connections had little luck, and it could be daunting, even traumatic, to try to convince physicians that a sexual assault had really occurred, or that a health threat was serious enough to qualify them for an exception.

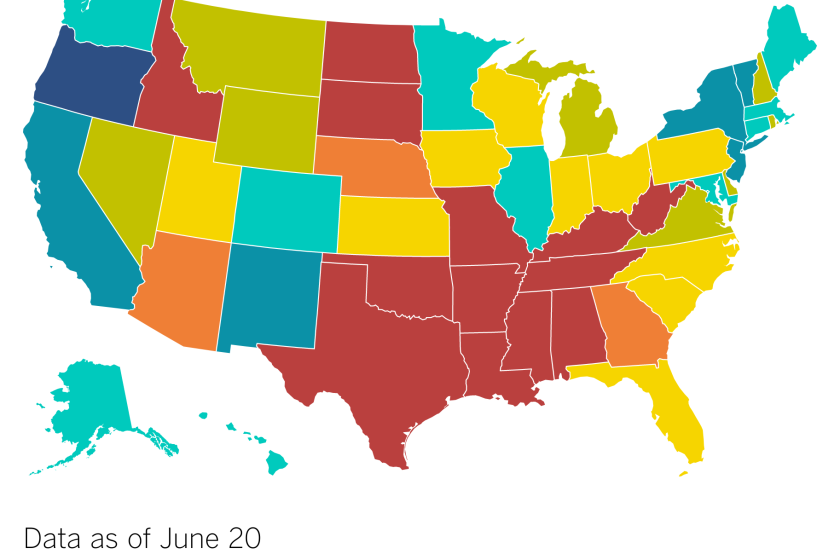

A year after the Supreme Court overturned Roe vs. Wade, leaving abortion decisions to states, where is abortion banned or protected? What comes next?

The post-Roe generation of abortion-ban exceptions are even more gravely problematic. The legislators who passed “trigger bans” before Dobbs, or fresh bans afterward, have often authorized punishments for doctors — and others in women’s support networks — that are much harsher than any that were common before 1973, including life in prison, the penalty in Texas for doctors.

Many of the new abortion statutes copy model language developed by antiabortion groups anxious that any exception could become a loophole for abortion on demand. For example, an exception for sexual assault could invite women to “cry rape.” Or if health dangers included risks to mental well-being, it could be too easy for women to get permission to legally terminate a pregnancy.

The new bans seek to eliminate discretion for physicians as well. Some, creating so-called affirmative defenses, require doctors to prove they are innocent rather than mandating that prosecutors establish their guilt.

State and local officials are trying to concoct new ways to block abortion funds, private nonprofits that help people travel to states that still provide abortion care.

As important, leading antiabortion figures oppose exceptions as a matter of principle. They embrace the idea that a fetus is a rights-holding person, and therefore no exception can be justified if the unborn child is by law treated like the rest of us. Even though — as Cox’s case shows — Texas’ ban makes an exception almost impossible, for Americans opposed to abortion, it represents compromise.

In other words, the goal of the new bans is primarily to protect fetal life. Exceptions appear in virtually every law, but their purpose is more to deter patients viewed as undeserving — unless you can prove your imminent demise, for example — not to safeguard women’s health.

Cox’s lawsuit is far from the only attempt to clarify or challenge abortion-ban exceptions. A plaintiff in Kentucky has filed a class action seeking permission for an abortion. Lawsuits in Texas, Tennessee and Idaho argue that if state exceptions cannot be more broadly interpreted, then the laws themselves are unconstitutional. In some states, courts have already weighed in on the constitutionality of specific exceptions, with more cases likely to follow.

The same message emerges from these cases, whether plaintiffs like Cox win or lose, and perhaps especially if they fail. The exceptions Dobbs brought into effect do not work the way many Americans might have guessed, and may be designed not to work for patients at all. When the state’s interest in fetal life clashes with real health threats faced by women, patients will always find themselves on the losing side.

Mary Ziegler is a law professor at UC Davis and the author of “Roe: The History of a National Obsession.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.