Opinion: What we can learn in the ‘era of cognitive challenges,’ when politicians and celebrities suffer from brain disorders

- Share via

Rock Hudson’s death in 1985 from AIDS started a robust and overdue public discussion about the disease. Until then, despite pleas from those in the most affected communities, AIDS had been in the shadows.

A decade later when Ronald and Nancy Reagan announced that the former president suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and would recede from public life, the result was similar: Suddenly a degenerative illness that had once been discussed in hushed tones, that for some had carried an unfair sheen of shame, was in the spotlight.

Trump was the first president to take office after turning 70. Now we have a slew of septuagenarians running.

Today, as baby boomers reach senior citizenship and as diagnostics improve, we live in what you could call the Era of Cognitive Challenges. Again and again, politicians, actors and other public personalities wrestle visibly with brain disorders of varying levels of severity.

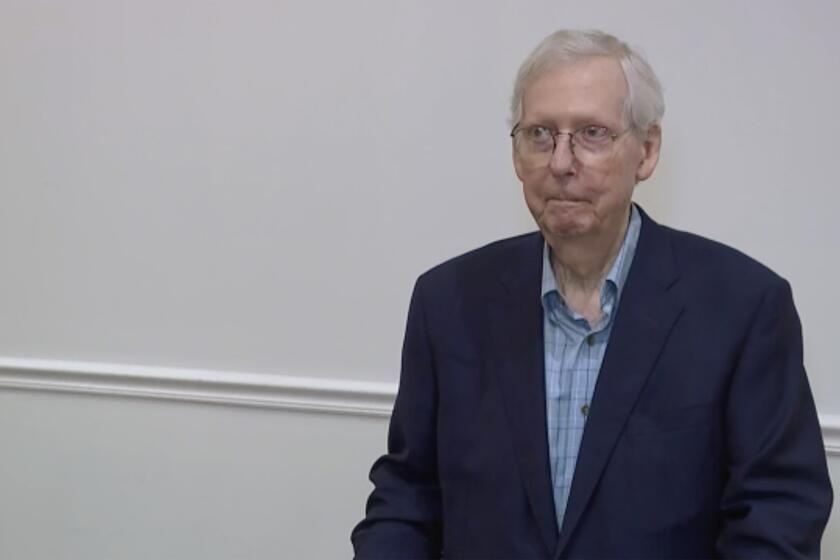

While there are many examples, even collectively they aren’t sparking productive conversations such as those after Hudson’s death and Reagan’s disclosure. When a brain disorder appears to manifest in the news — for instance the presidential front-runners misspeaking or Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) freezing in front of news cameras — the medical community and the news media are broadly failing to advance the public’s understanding of these impairments and available treatments.

Employees and job applicants are increasingly being subjected to AI and other tech designed to evaluate their cognitive ability and activity.

Such information could aid millions of people who are (or should be) diagnosed with the same diseases. Opportunities are being squandered to educate the world on highly complex conditions that many of us will one day face.

The public saw 81-year-old McConnell freeze on camera this summer — not once, but twice. The Capitol physician, Brian P. Monahan, blew a golden teachable moment when he announced that the minority leader showed “no evidence” of having experienced a stroke or seizure and was cleared to return to work. That was it. Few suspicions were allayed. No useful information was conveyed. How did that serve the public?

New medications such as lecanemab offer at best modest effects and major expenses. But dementia can be forestalled with practical and affordable measures.

I did not examine McConnell personally, but even from the video clips it is clear to me what happened. He experienced a type of seizure resembling a “petit mal” that occurs from time to time in older people. In fact, about 6% of the older population will experience seizures at one point or another.

It is eminently treatable if sufferers will only seek help. The right prescription will reduce these spells or even clear them up within days to weeks. Anyone going through what McConnell showed probably should receive such treatment and be barred from driving for at least 90 days while the drugs have a chance to do their work. Otherwise he is perfectly capable of doing his job.

If McConnell takes a break from the Senate, it’ll be for health reasons, not age alone. Just as questions surrounding Sen. John Fetterman aren’t about his age but about his capacity to do the job.

Untold numbers of older Americans enduring similar lapses would also be capable of continuing their normal lives if they received a diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Far too many are going untreated because we aren’t having the conversations: We don’t know whether McConnell is allowed to drive. We don’t know whether he’s on anti-seizure medications.

Similarly, after then-Lt. Gov. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania suffered a stroke while running for the Senate, he disclosed little. He could have been more upfront, rather than acting as though the stroke and subsequent cognitive differences were embarrassing — but hey, that’s politics.

He was later treated for severe depression, which he approached with admirable candor when he made the wise choice to be hospitalized. But once again, instead of thoughtful discussions about his physical and mental health challenges, much of the political world seemed more concerned with his Senate attire of hoodies and shorts.

For every healthy 80-year-old like Mick Jagger, there are more suffering from age-related decline. The presidency, Congress and Supreme Court need upper age limits.

Some physicians and news organizations did their best in these moments to advance understanding and public health, but overall the nation missed much-needed opportunities to improve diagnosis and treatment of common psychiatric and neurological conditions.

One reason many patients are hesitant to discuss cognitive issues, it seems, is that they strike at the heart of who we are, our very personalities, more so than conditions that are thought of as physical. When human lapses are exploited for political points, this stigma is only aggravated — as when President Biden speaks haltingly, or when former President Trump says “Sioux Falls, S.D.,” when he means “Sioux City, Iowa.”

Since actor Bruce Willis’ family announced his cognitive issues in 2022, they have given us a template for how to think and talk about cognitive health. The actor was first diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia, which can be an early harbinger of Alzheimer’s or frontotemporal dementia, which affects speech and the ability to communicate. This brought some attention to the disorder, although much of the public conversation focused on whether the star had been manipulated by producers.

After additional tests, and the disease’s relentless march, Willis is now confirmed to be living with frontotemporal dementia, which can affect a person’s ability to communicate and organize the day, as well as insight into their own illness.

The actor’s wife, Emma Heming Willis, was recently on “The Today Show” to talk about her husband’s struggle, with an eye toward educating the wider world about frontotemporal dementia. At her side was Susan Dickinson, the chief executive of the Assn. for Frontotemporal Degeneration.

Heming Willis was calm and cool as she discussed what must be a painful time for everyone involved. Because she is sharing her experience, others may receive a diagnosis and treatment — and feel less alone. We can all learn from her act of service.

Keith Vossel is a professor of neurology at UCLA.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.